That is the goal of a new multi-million-dollar project set to kick off at Cancer Research U.K. Cambridge Institute this May. The project’s aim is to develop virtual reality and 3D visualization tools to help oncologists and other cancer researchers create and analyze 3D maps of (initially breast cancer) tumors.

“Pathologists take a very thin slice of a tumor, look at this flat object under a microscope, and then make judgments that affect the lives of patients,” researcher Greg Hannon, who will head up one part of the project, told Digital Trends. “We think that we can give them much more complete information by presenting these objects in much greater and with much richer information.”

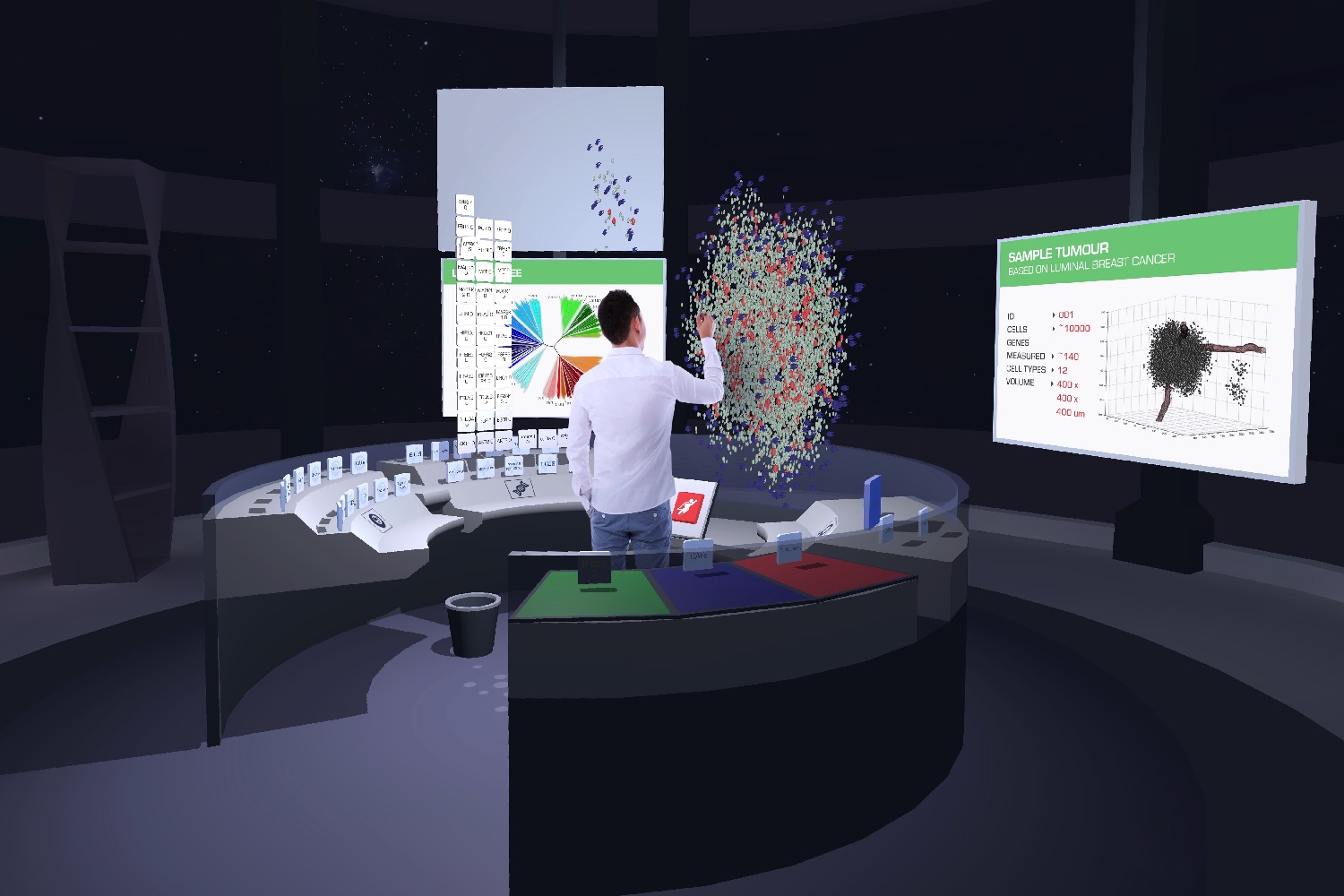

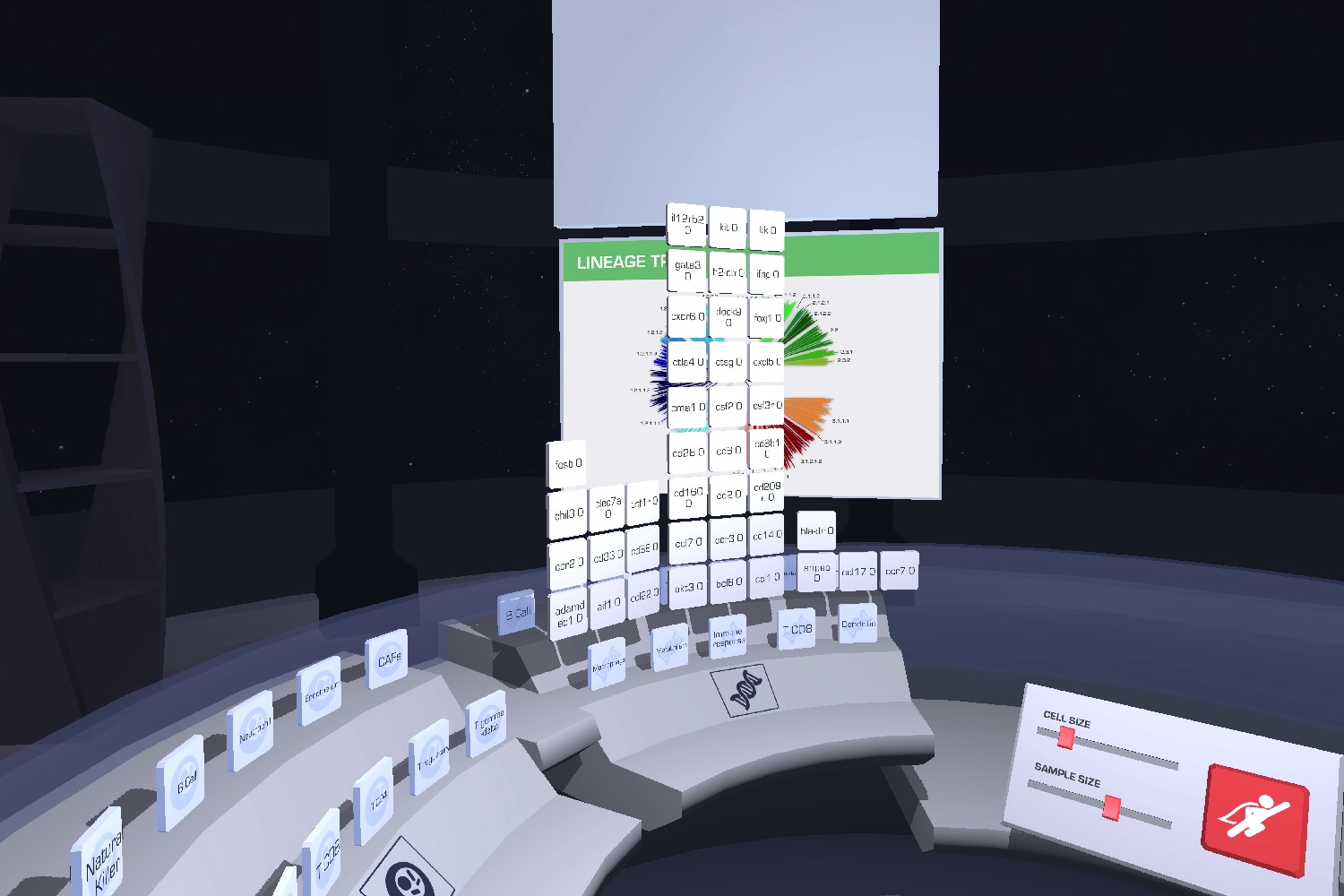

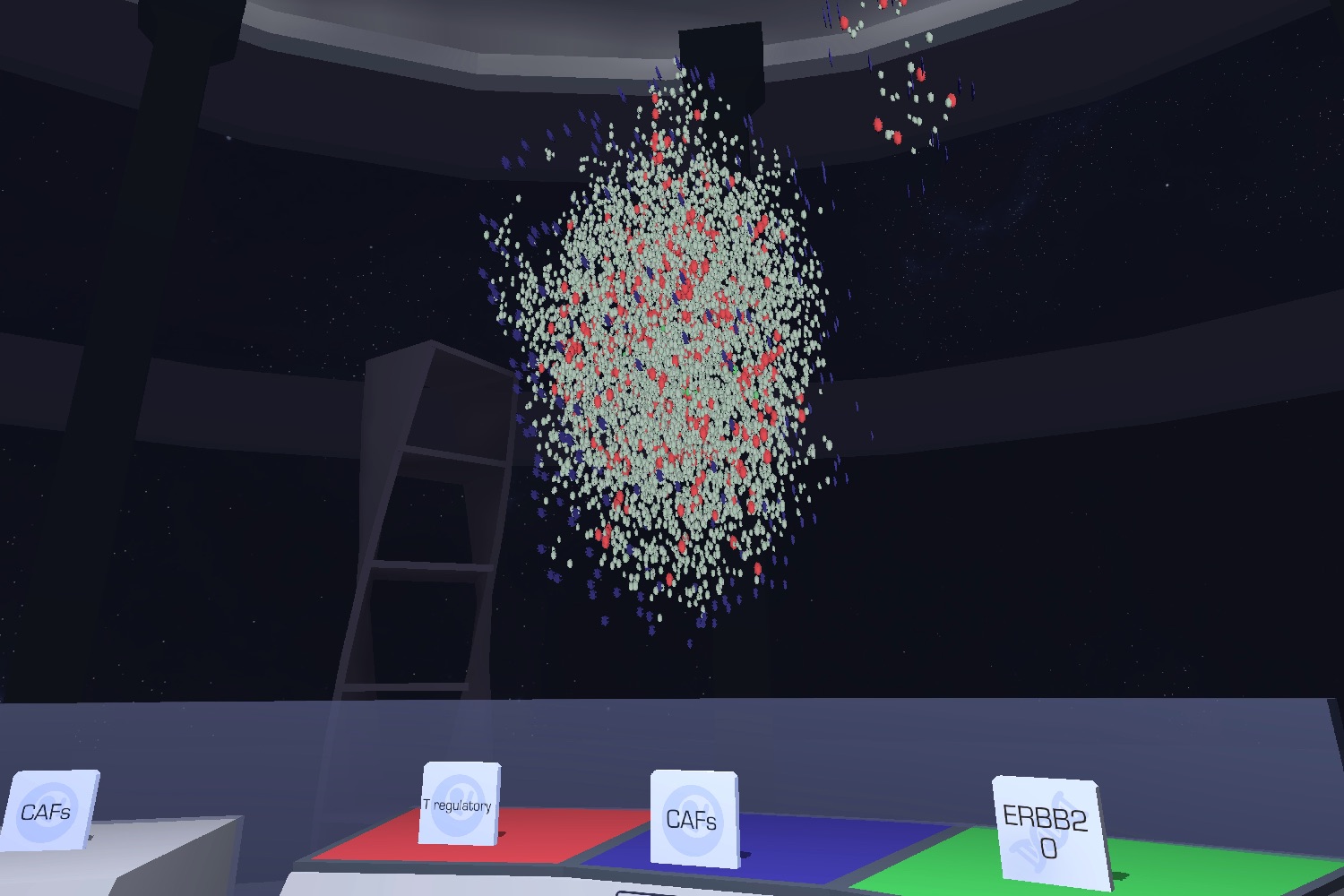

The VR tools the team is developing will give researchers the ability to “walk into” virtual 3D tumors and analyze them in extreme detail — even down to the level of a cell’s particular genetic makeup. It will be useful as an educational tool, a way for surgeons to better get to grips with tumors, for doctors to visualize information for patients so that they feel more involved with the treatment process — just to name a few possible use-cases.

“I wasn’t very educated in [virtual reality when I started the project],” Hannon said. “Originally I was thinking about 3D projectors. I hadn’t paid too much attention to virtual reality and had no idea how far consumer model VR devices had come. Then I had a conversation with an app developer who sits on a grants committee that I’m a part of. I was telling him about the project and he told me how far VR had come in just the past two to three years. He suggested I get in touch with Owen Harris, a teacher, VR developer and game designer in Dublin, who we’ve ended up working with. That’s how the project really started.”

Despite the fact that the project’s not officially due to commence for another few months, Hannon said the team has already developed a “pretty highly functioning prototype” of the VR visualization system. There is still a lot more to do, though.

“The harder bit is generating the data that will go into this,” he said. “We’re measuring things that have never been measured before, on a scale that’s never been measured. We’re hoping to have a couple of data sets of 100,000 cells sometime in the coming year. But to make something like this useful you have to do thousands of tumor samples. I think that about three years from now we’ll really be able to start extracting interesting and meaningful information.”