Drug testing is tricky business but it’s an essential step to bringing safer medications to the market. Pharmaceutical drugs are designed for a specific purpose, to treat a given ailment, but often come with a slew of “side effects may include…” — drug trials attempt to identify those side effects.

Almost all of these side effects are undesirable, but many of them are worth the risk as long as they treat the condition. Others, however, can have serious consequences.

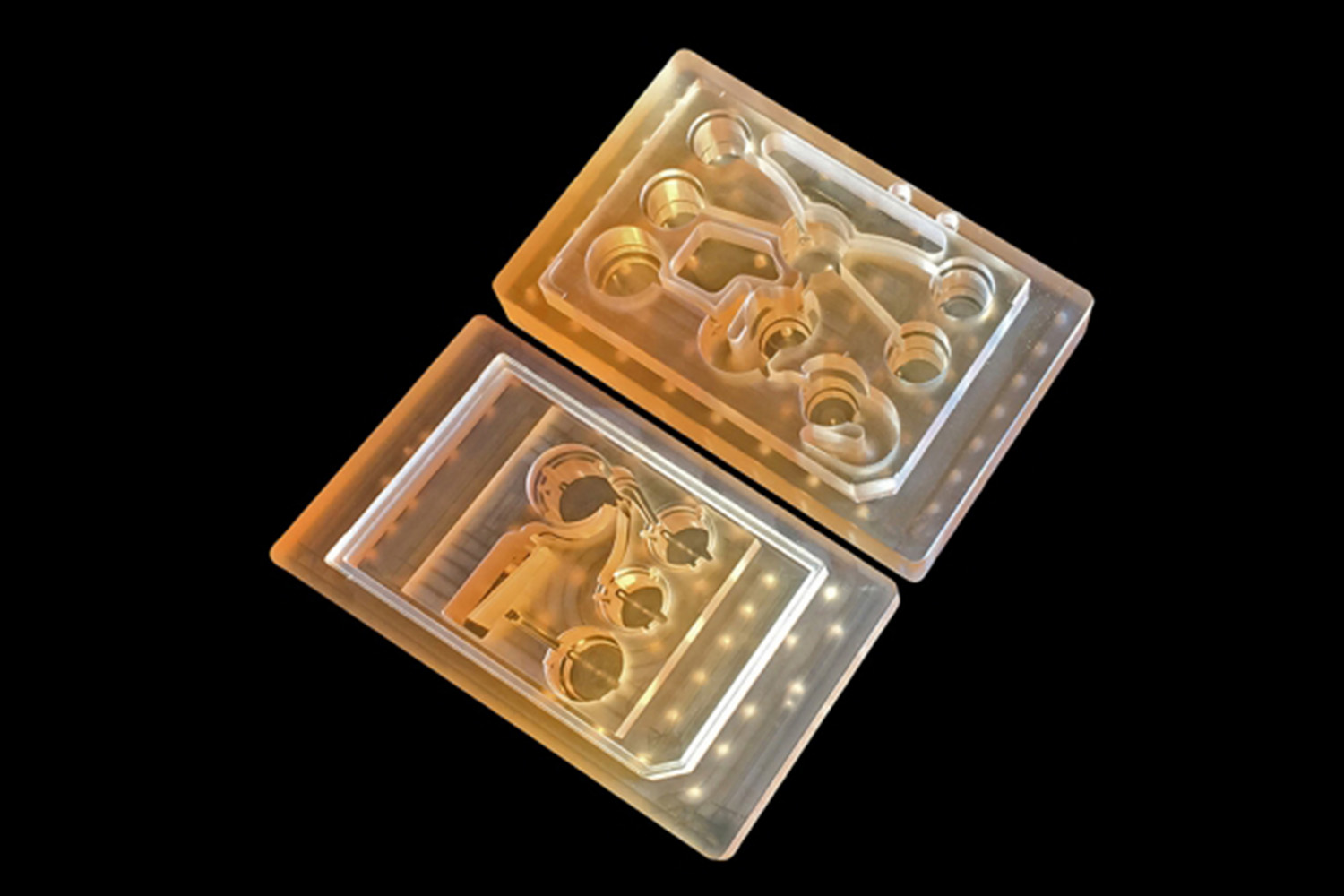

Now a new technology called a microphysiological system — or “body on a chip” — may help identify potential problems faster. Developed by engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) the device is made up of a microfluid medium that connects tissues engineered from up to 10 different organs, allowing it to mimic mechanisms of the human body for weeks on end. With this system, which was detailed in a paper published last week in the journal Scientific Reports, the researchers hope to reveal how drugs designed to treat a specific organ might have an effect on other organs in the body.

“Some of these effects are really hard to predict from animal models because the situations that lead to them are idiosyncratic,” Linda Griffith, a professor of biological and mechanical engineering, and one of the senior authors of the study, said in a statement. “With our chip, you can distribute a drug and then look for the effects on other tissues, and measure the exposure and how it is metabolized.”

After researchers develop a pharmaceutical drug, they test it through a series of preclinical animal trials intended to demonstrate the drug’s safety and effectiveness. However, Griffith points out, humans aren’t exactly like other animals. Sure, we share a similar biology with lab animals, but the relation isn’t always one to one.

“Animals do not represent people in all the facets that you need to develop drugs and understand disease,” she said. “That is becoming more and more apparent as we look across all kinds of drugs.”

To get around this obstacle without testing on human subjects, researchers have developed “organs on chips,” miniature replicas of organs composed of engineered tissue.

While the basis of this technology isn’t anything new, Griffith and her colleagues are the first to fit so many tissue types onto a single open chip, enabling them to manipulate and remove samples.

The organ tissue types fit onto the chip include liver, lung, gut, endometrium, brain, heart, pancreas, kidney, skin, and skeletal muscle, each containing between 1 million and 2 million cells.

While the system is promising, it won’t be used to its full potential anytime soon. For now, Griffith and her team are using the system for more restrained studies, including just a few organs like brain, liver, and gastrointestinal tissue to model Parkinson’s disease.