Nvidia’s unveiling of its next-generation 2000-series graphics cards at Gamescom should have been a momentous occasion for gamers. More than two years on from the release of its fantastic Pascal line up of hardware, we finally got a look at Nvidia’s true, next-gen power. Or did we?

We can safely assume that the GeForce RTX 2000-series graphics cards will be better than their predecessors at powering games. But for all of the talk of ray tracing and tensor cores, there’s been precious little discussion of how these cards will actually perform in games people play today. What little data we’ve been given on that front seems deliberately muddied and cherry-picked.

So, are these gaming cards with AI benefits or AI cards that can game?

The new Nvidia showing its face

Nvidia was once a dedicated gaming hardware company, but these days, it puts a lot of energy and investment into other fields. In 2018, Nvidia’s GPUs are used in autonomous vehicles, AI and deep learning processing, and powering supercomputers and data centers. It seemed to be a happy accident that Nvidia’s gaming technology had real-life applications in burgeoning fields of interest.

No one could blame Nvidia for wanting to capitalize on these newfound revenue streams. There is obviously crossover in what makes a good AI GPU and what makes a good gaming GPU, and that’s what we’re seeing in this new graphics card architecture, dubbed Turing. It’s a robust platform for a company looking to spread into new verticals as efficiently as possible.

But here’s the problem: The fraction of Nvidia’s business that is focused on gaming is shrinking by the day, and due to its near-monopoly control of the market, rarely is forced to make aggressive moves in the space. Just consider its lackluster response to the 2017-2018 graphics card pricing crisis as an example of how the company can comfortably sit on its hands and let the profits roll in.

Why deep learning and ray tracing?

Rather than deliver practical, performance-driven updates in its new cards, Nvidia has found two gaming applications of its new newfound interest in AI. The vast majority of Nvidia’s Gamescom talk was spent discussing these new technologies, and yet their actual application to gaming is fairly limited right now.

What about performance in games people actually own?

The first is what it calls “deep learning super sampling” (DLSS), which is powered by the presence of Nvidia’s tensor cores. These are processors designed specifically to run AI. The application in gaming is effectively an AI-driven anti-aliasing solution.

As nice as all that sounds, these tensor cores weren’t designed specifically to perform that task. In fact, they were introduced in early 2017 in the Titan V graphics card. Although powerful at certain gaming tasks, that card was marketed almost exclusively for deep learning and AI development., the tensor cores playing a major role in that capability.

And then there’s the new ray tracing capabilities. Powered by another new piece of technology, the RT cores, they’re benefit to gaming is a bit more clear. Ray tracing allows for the creation of dynamic lighting, reflection, and shadow effects in environments — and Nvidia spent plenty of time showing off the difference it made in games. But still, ray tracing is not a functionality that’s exclusive to making games look prettier. Nvidia’s new RTX Quadro enterprise cards, which were announced a week before, benefit from the RT cores as well. It’s a technology that’s being sold to visual effects animators too.

The multi-purpose functionality of these two innovations doesn’t make them negligible, but it certainly marks a sea change in the way Nvidia will develop its hardware in the future. They won’t offer much to the vast majority of gamers, due to the lack of support. There are precious few games that currently support ray tracing, and the same goes for DLSS. If these new features were add-ons to some significant performance gains as well, that’d be understandable. But we’ve dug into the numbers, and well, they don’t look all that promising.

Don’t trust the numbers

Rather than talk about these new cards in terms gamers care about, Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang claimed Nvidia had to invent new methods and terminology to measure the performance. We learned all about “Giga rays per second” and “RTX-OPS.” We were told that an RTX 2070 was more powerful than a Titan XP and that a 2080 Ti was six times more powerful than anything Pascal had to offer when it came to ray tracing in supporting games. But again, what about performance in games people actually own?

The additions of DLSS and ray tracing appears to have a negative impact on the power requirements of Nvidia’s new cards too.

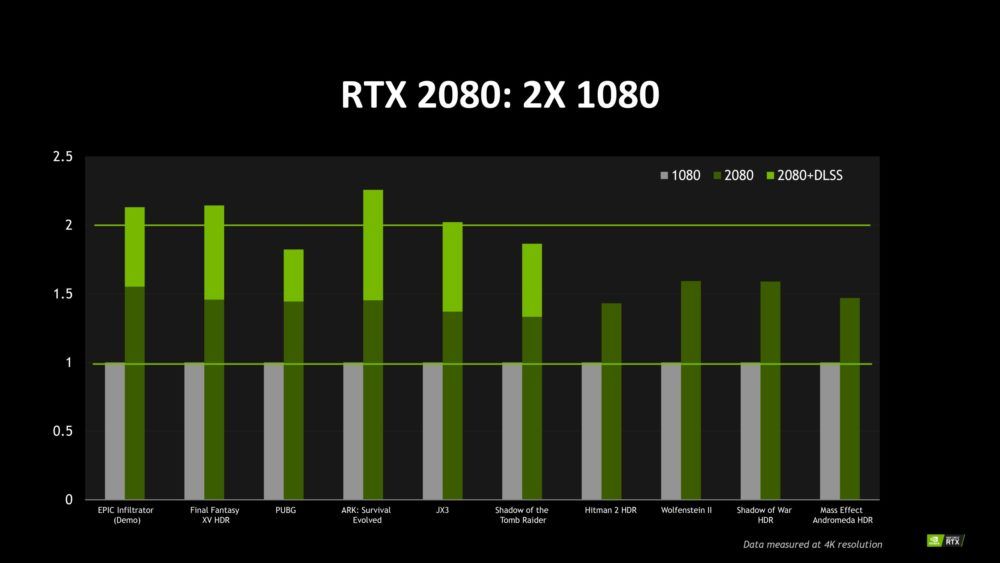

To counter claims that these surprisingly expensive new graphics cards weren’t big performers, Nvidia followed up a few days later with some much more generalized benchmarks. However, they only made hardware enthusiasts like us more suspicious. The games which show the biggest advantage of the RTX 2080 are those using that new DLSS, AI-driven anti-aliasing technology.

Since the 1080 wasn’t designed to run DLSS, it is no surprise that it’s poor at doing so, making that relative comparison far from conclusive.

Of all of the games listed, only three show a relative performance increase of 1.5 times between generations. Most are much closer to 1.3 and the graph gives us no indication of what settings were enabled. Nothing in that graph equates to framerates either. It’s a pure relative comparison, which without a lot of qualifying information, tells us very little.

And when we did get frame rates, most are not for the same games as in the original graph, meaning we can’t cross-reference. Neither do we know what settings these games were run at beyond the 4K resolution.

Gaming at 4K at above 60 FPS is a great achievement, but these numbers aren’t vast increases over what was possible with last-generation cards. Indeed they seem relatively comparable to a 1080 Ti. Guru3D managed similar numbers in its Resident Evil 7 testing, and we weren’t far off such framerates in our Final Fantasy XV testing with that last-gen card.

But wait! It gets worse.

It’s the deliberate lack of clarity in Nvidia’s benchmarking numbers which feels so insulting to gamers.

The additions of DLSS and ray tracing appears to have also had a negative impact on the power requirements of the new cards too. Clock speeds have actually decreased this generation, but despite that dip and the use of more efficient GDDR6 memory, power requirements have gone up, which in turn has warranted an entirely new dual-fan cooling solution.

CUDA cores have gone up across the board, which should equate to an increase in performance. The number leap is relatively comparable to the jump between the 900 and 1000 series, although as a percentage, that’s less impressive this time around. While the 2080 and perhaps 2070 could potentially end up close to 1080 Ti speeds, when the 10-series cards’ prices are crashing to far less than their next-gen counterparts, it makes the 2000-series far less attractive.

And yet even if these cards are only a little more powerful than the Pascal generation, they’ll still be the most powerful graphics cards available. With limited competition at the top end from AMD, Nvidia can effectively set its own prices and arbitrarily decide how a top-end card should perform. It could even hamstring the gaming performance of its new-generation GPUs to make them equally attractive to AI developers with little fear of a drop in market share.

Do these cards really put gamers first?

It seems likely that the actual, real world, general gaming performance of the new 2000-series cards won’t be quite so monumental as we hope, nor nearly as good as Nvidia suggested. Yes, they’ll be able to do ray tracing — though it may require a big performance hit. And the new DLSS technique is pretty, but both technologies will only have any effect in games that actually support it. In everything else, this looks much more like a standard generational leap in gaming power, if not a bit less than that.

But it’s the deliberate lack of clarity in Nvidia’s benchmarking numbers which feels so insulting to gamers who have struggled through well over a year of bad GPU pricing in the hopes of a new-generation offering a meaningful upgrade. Instead, Nvidia has obfuscated how powerful the cards are in general gaming and pushed the introduction of new ‘features’ which seem equally, if not more, applicable to other industry’s interests entirely.

Though the 2000-series is an impressive line up of graphical hardware, it doesn’t seem like technology built with gamers in mind. It smells of enterprise kit with some gamer racing stripes stuck on the side.