Closed captioning has been a part of our television-watching experience dating back to the 1970s; allowing anyone to follow along with what’s being said by reading subtitles at the bottom of the screen. Today, it is legally mandated that not only should home televisions sold in the U.S. contain caption decoders, but the overwhelming majority of programs — both pre-recorded and live — must offer captioning.

Could TV one day offer something similar: only not just telling viewers what is being said, but whether or not it is truthful? The TL;DR version: At least one major research project in the U.S. believes that it could.

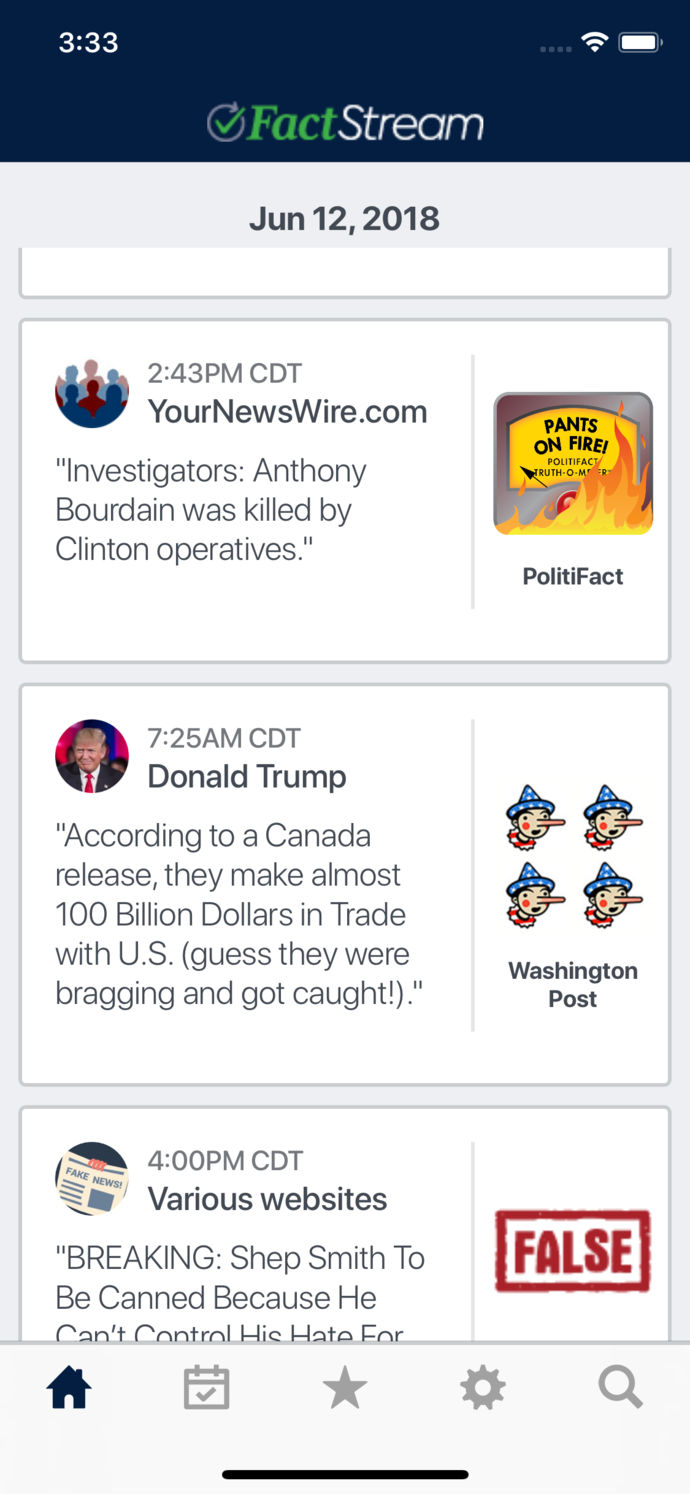

The idea of fact checking politicians is nothing new, of course. PolitiFact, FactCheck.org, and the Washington Post‘s Fact Checker are all well known examples of systems set up to try and keep politicians honest by calling them on their exaggerations, flip-flops or even outright lies.

What all three of these have in common, however, is that they rely on human curators to carry out their in-depth fact-checking process. That’s something that a Duke University research project is hoping to change. They are working to develop a product in time for 2020’s election year, which will allow television networks to offer real-time on-screen fact-checking whenever a politician makes a false statement.

“We’re trying to ‘close the gap’ in fact-checking,” Bill Adair, creator of PolitiFact and the Knight Professor of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke University, told Digital Trends. “Right now, if people are listening to a speech and want a fact-check, there is a gap: they have to go to a website and look it up. That takes time. We want to close that gap by providing a fact-check at the moment they hear the factual claim.”

How it works

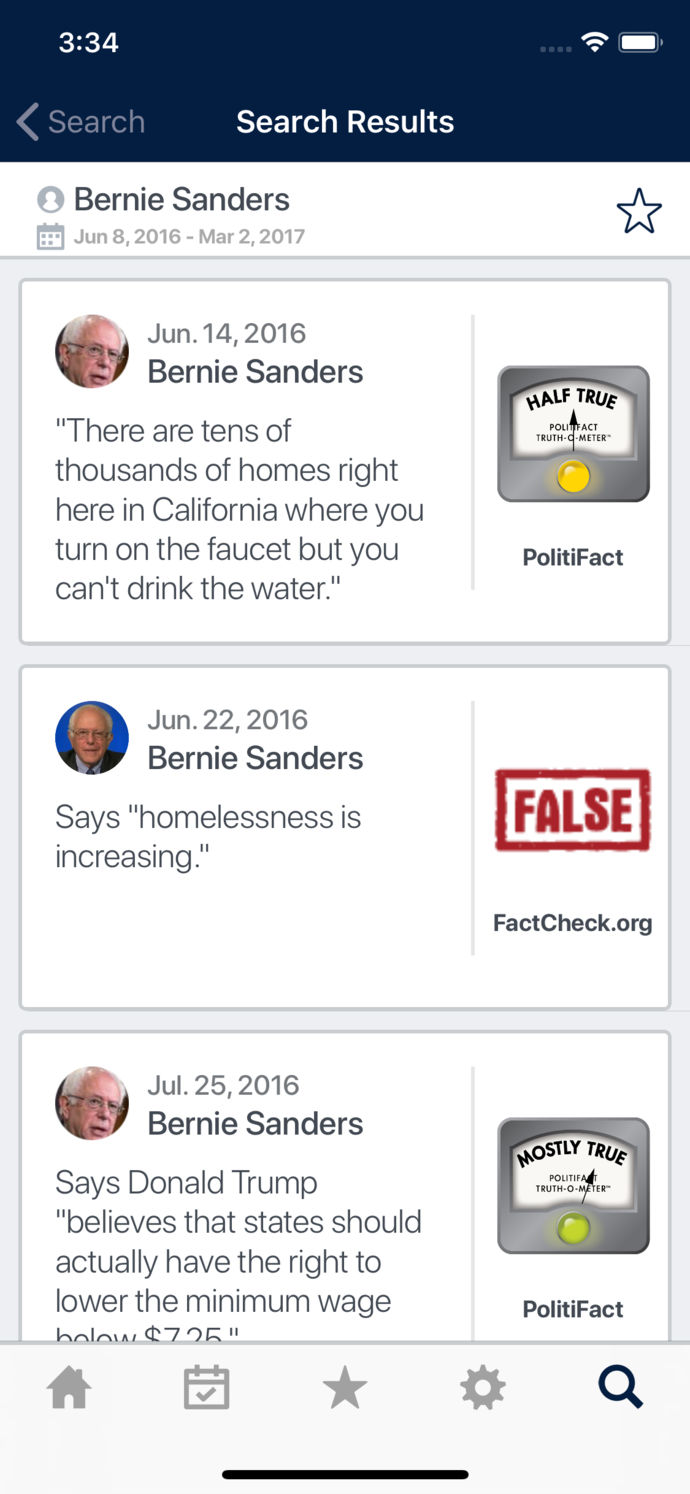

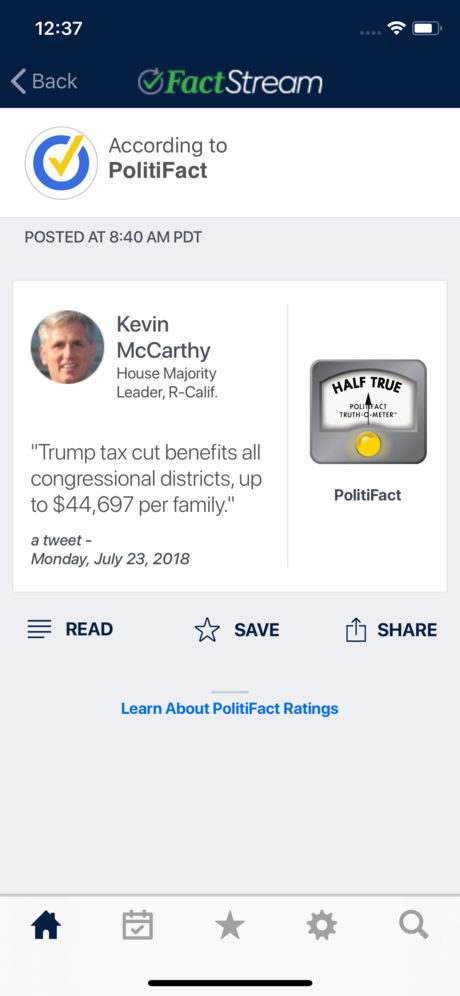

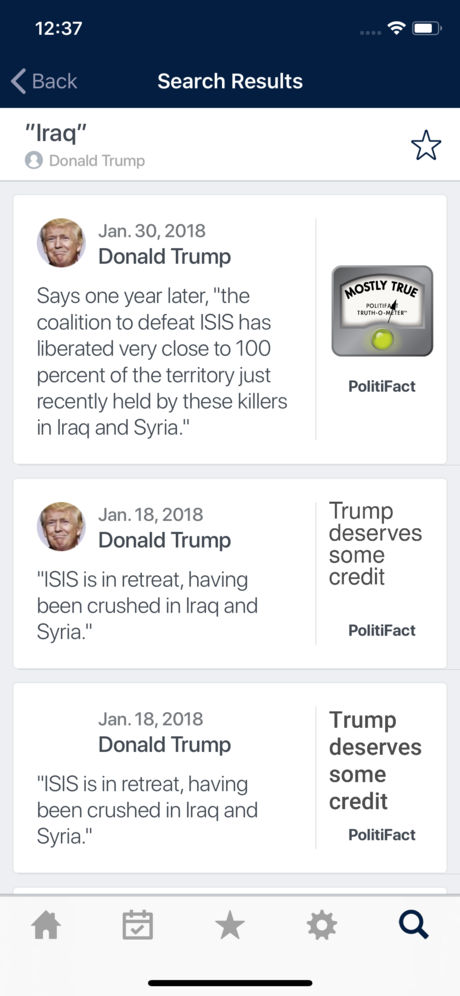

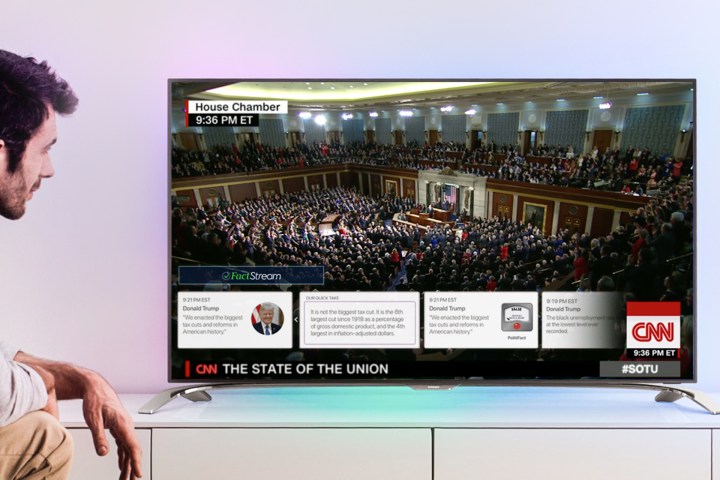

Adair has previously overseen the creation of FactStream, a “second screen” iOS app that provides real-time push notifications to users whenever a questionable statement is made. In some cases, these direct users to a related fact check online. In others, they provides a “quick take” which fills in some of the additional facts and context. FactStream was created as part of Duke’s Tech & Check Cooperative, which has been developing automated fact-checking technology for several years.

The idea of a television version of this app is that it would offer similar functionality, but more deeply baked into the TV-viewing experience. “[It’s an automated approach which] uses voice-to-text technology, and then matches claims with related fact-checks that have been previously published,” Adair continued “When this product is built, we plan to provide the fact-checks right on the same screen as the video of the political event.”

The system would spring into action when certain phrases, which have been fact-checked before, are mentioned. According to Adair, it is likely that there would be an average of one fact check approximately every two minutes. While such a system could theoretically work in real time, networks would probably air speeches or debates on a small, one-minute delay in order to ensure smooth running of the technology.

It’s easy to see the concern over how an automated fact-checking tool could be open to bias.

A focus group was shown a demonstration of the technology in action late last year: offering demo speeches by President Trump and Barack Obama with the inserted fact checking. It was reportedly met with a favorable reaction. However, there’s still a way to go until it’s ready for prime time.

“We’re making good progress,” Adair said. “We’ve overcome some hurdles in voice-to-text and claim matching, which are the two big computational challenges. But we still need to improve the quality of our search results, and make sure we can deliver high quality matches quickly. We’re planning to have it ready for a beta test before the end of the year.”

Networks aren’t yet publicly talking about introducing a real-time automated fact-checker, although Adair insists that there is demand for such a product.

The problem with fact-checking

Would such a tool work — or find mass-approval — though? After all, we think nothing of existing automated tools like spell checks — but whether there’s a “u” in “color” is a whole lot less politically charged than today’s partisan politics.

It’s easy to see why the idea of an automated fact-checking system would appeal. Many people have argued that the spread of “fake news” was a factor in major recent political events around the world. Just like a previous tool such as the breathalyzer took a subjective problem (whether a person is capable of safely driving) and standardized it into an objective measure, so too could an A.I. fact-checker do the same for untruths.

However, it’s also easy to see why people would be worried by it — or fear that an automated tool, designed to give the impression of objectivity, could be open to bias.

Will we eventually see the rise of automated fact-checking by artificial intelligence? Should A.I. even be involved?

The jury is still out on whether increased fact-checking can sway the opinion of viewers, or make politicians more truthful. Some studies have concluded that people are more likely to vote for a candidate when fact-checking shows that they are being honest. In other cases, corrections may not have such a big impact.

Ultimately, the problem is that truth is difficult. Spotting more obvious lies is relatively low-hanging fruit, but dealing with this kind of complexity is something machines are not yet capable of. It is perfectly possible to point out what are technically true facts, but to mislead people by selective cherry-picking of statistics, leaving out information, or taking fringe cases and using them to make sweeping generalizations. These are tasks that automation is not currently equipped to handle.

“At this point, that’s beyond the capability of our automation,” Adair admitted. “We’re just trying to do voice-to-text and get high quality matches with previously published fact-checks. We are not able to write fact-checks.”

Of course, stating that A.I. will never achieve something is the siren song which has driven the industry forward. At various times, people have argued that A.I. will never beat humans at chess, fool humans into thinking they are speaking with another person, paint a picture worth selling, or win at a complex game such as Go. Time and again, artificial intelligence has proven us wrong.

Will automated fact-checking be the next example of this? We’ll have to wait and see. For now, though, this may be one task too many. But we look forward to being fact-checked.