You may have heard about artificial intelligence algorithms which can smell diseases, such as Parkinson’s, Crohn’s or even liver failure. But here’s a new one: An A.I. smartphone app that’s able to hear ear infections.

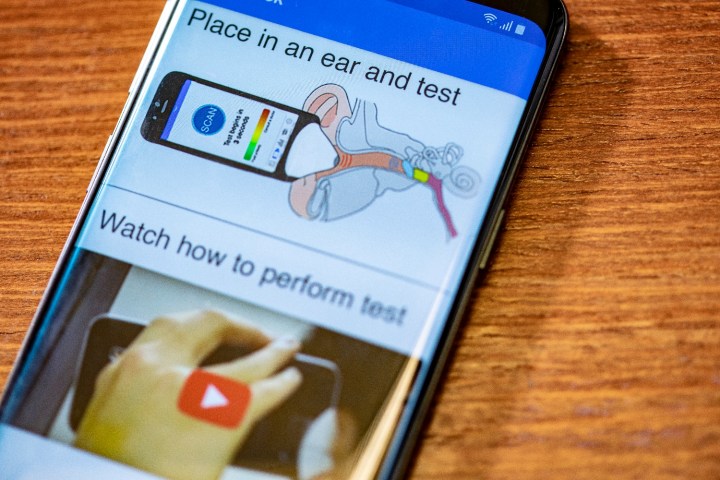

That’s something a team of researchers from the University of Washington have been working to develop. It works by detecting fluid behind the eardrum by using a smartphone’s microphone and speaker, combined with an ordinary piece of paper. The app works by producing a series of soft “chirps,” between 1 to 4 kHz, which are played into the patient’s ear through a small paper funnel. Depending on how these sounds are reflected back to the phone, the app is able to detect the likelihood of fluid behind the eardrum with 85% accuracy. That figure is the same as the specialist tools doctors currently use to detect fluid in the middle ear.

“At a high level, it is like tapping a wine glass,” Shyam Gollakota, an associate professor in the University of Washington’s Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering, told Digital Trends. “Depending on how much liquid is in it, you get different sounds. In our case, we are not tapping but sending sounds, and using machine learning on these sounds to detect the presence of liquid.”

The work is particularly focused on diagnosing ear infections in kids. Ear infections are the most common reason for parents bring their children to see a pediatrician, according to the National Institutes of Health. The researchers on the project evaluated their system at the Seattle Children’s Hospital surgical centers by testing it on 98 pediatric patients, aged between 9 months and 17 years.

“The definitive way to know if there is fluid is to make an incision in the eardrum,” Gollakota explained. “We evaluated our system with patients who were undergoing ear tube placement, during which an incision is made in the eardrum to drain any fluid. We used our smartphone system on the morning of the ear tube surgery and compared the results with the ground truth of what happened during surgery.”

The team has started up a healthcare company, Edus Health, which will distribute the app and make it widely available. “We have our app running in real time on a smartphone, and we are planning on obtaining FDA approval by the end of the year,” Gollakota said. The app works across a range of smartphone models, so long as the devices have co-located microphone and speakers. “[This] is true for almost every smartphone,” he said.