This article is part of Apollo: A Lunar Legacy, a multipart series that explores the technological advances behind Apollo 11, their influence on the modern day, and what’s next for the moon.

An American flag wasn’t the only thing we left on the moon. Fifty years after the first moon landing, the Hasselblad 500EL that captured one of the most iconic images in history remains on the dusty lunar surface, alongside the footprints of astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin. Although the crew members of Apollo 11 became the first humans on the moon, the Hasselblad brought the moon back to the rest of the world.

The Hasselblad 500C that initiated a relationship between the camera company and NASA several years before the launch of Apollo 13 was a technologically advanced camera at the time, with a leaf shutter and automatic aperture stop down. Wally Schirra, a NASA mission pilot and photo enthusiast, suggested the 500C, a camera he already owned, be adapted to document human space travel. Seven years before the first Hasselblad would drop to the dusty lunar surface, NASA and the Swedish camera company worked together to modify cameras for the extremes of space.

The camera shed its viewfinder, reflex mirror, auxiliary shutter, and even the leather cover to minimize the camera’s weight impact on the mission. The modified 500C then gained a 70-exposure film magazine instead of the traditional dozen photographs in a single roll. The retrofitted camera was taken aboard the Mercury 8 in 1962, taking photographs while orbiting Earth and paving the way for Hasselblad’s first trip to the moon.

After success with the modified 500C, Apollo 11 was equipped with two medium-format cameras, the Hasselblad 500EL Data Camera or HDC and a Hasselblad Electric Camera (HEC). The first, which was the camera that snapped the images on the surface of the moon, was outfitted with a Zeiss Biogon 60mm F5.6 lens and a specially designed film magazine that allowed for 200 exposures on Kodak 70mm film. The second HEL camera used an 80mm F2.8 to capture images from inside the Eagle lunar module, and a third camera was used inside the Command Module — which remained in orbit — by crew member Michael Collins.

To cut weight for the return journey, the cameras, lenses, and accessories were left behind on the moon.

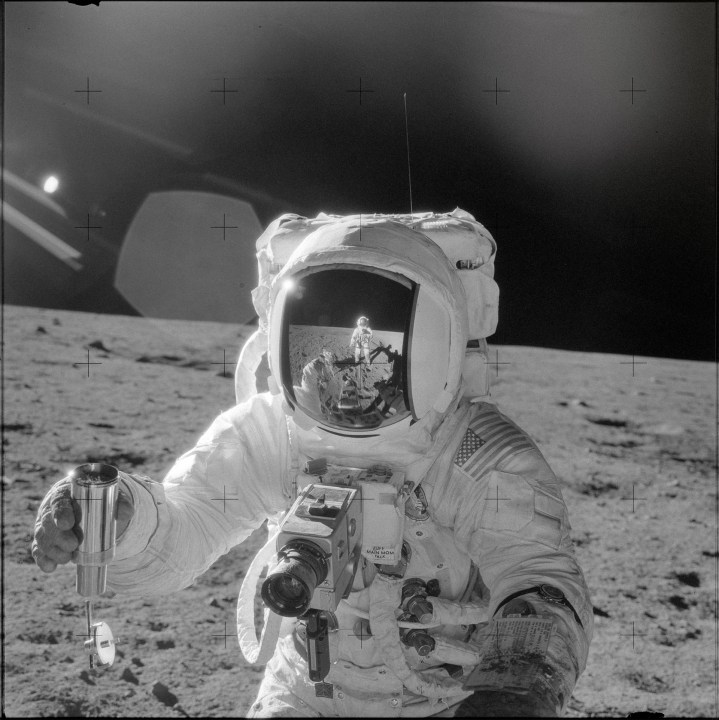

Like the 500C on earlier missions, the HDC camera was adapted to withstand the rigors of space, using silver paint to help the camera move between -85 degrees and 248 degrees Fahrenheit. A special plate was added to the camera to intentionally leave “+” marks in the images, which would later be used to make measurements and gather more data from the images. But, unlike the 500C, the Hasselblad cameras would take the virgin voyage to space on that first manned trip to the Earth’s only natural satellite.

Armstrong carried the camera onto the surface of the moon. Basic photography principals, as well as instructions on using specific Hasselblad cameras, were built into NASA’s training program, giving Armstrong the background necessary to operate the camera in space. The then-38-year-old was behind the iconic image of the Earth seen rising beyond the moon’s horizon, as well as shots of the flag on the moon and a moon “selfie” — way before selfie was even a word — where Armstrong himself can be seen reflected in Aldrin’s helmet.

The Hasselblads that made it to the moon were not the only cameras on board the first manned mission to the moon. A Kodak macro camera captured close-ups of lunar dust. Two 16mm Maurer cameras captured video, along with a camera mounted outside the lunar module and a color television camera on Colombia, the command module and the only part of the original spaceship that returned from the moon.

After an eight-day journey, the spacecraft that weighed more than 100,000 pounds at launch would return with a landing mass of less than 11,000 pounds. To cut weight for the return journey, the cameras, lenses, and accessories were left behind on the moon. Today, five Apollo missions later, a total of 12 Hasselblad cameras reside on the lunar surface.

It is one of Hasselblad’s proudest achievements to be part of space exploration history.

Without the digital technology to see if the images remained intact after the temperature swings found on the moon’s surface, there was no way for Aldrin to know if his efforts were successful upon pulling the film back into the Lunar Module. Even Hasselblad, in the original press release from 1969, admitted to nerves over whether the images would return intact after hanging from a cable in zero gravity. Company founder Victor Hasselblad picked up four color rolls of film to personally fly back to Sweden.

“We were even more satisfied,” the 1969 press release reads, “when the following telegram came from the United States regarding the black-and-white images that we, when this is written, have not yet seen. The black-and-white film from Hasselblad EL Reseau camera with 60 mm Biogon taken on lunar surface was developed and the results are absolutely perfect. NASA people call it 132 prize-winning pictures. Those of us at Hasselblad who smoke lit a victory cigarette, just as the Houston Technicians light their victory cigars after every successful splashdown.”

The Swedish camera manufacturer would continue to work with NASA and use feedback from the astronauts to further modify the space-bound cameras, including larger controls for working with spacesuit gloves, enhanced cooling technology, and other adjustments. Nine additional Hasselblad cameras would head to the moon on subsequent Apollo missions, before the final moon landing in 1972.

“It is one of Hasselblad’s proudest achievements to be part of space exploration history,” said Dan Wang, Hasselblad marketing director, North America. “We celebrate along with the aerospace community the anniversary of this awesome moment, and look forward to the next generation of innovators and explorers on Earth and beyond.”