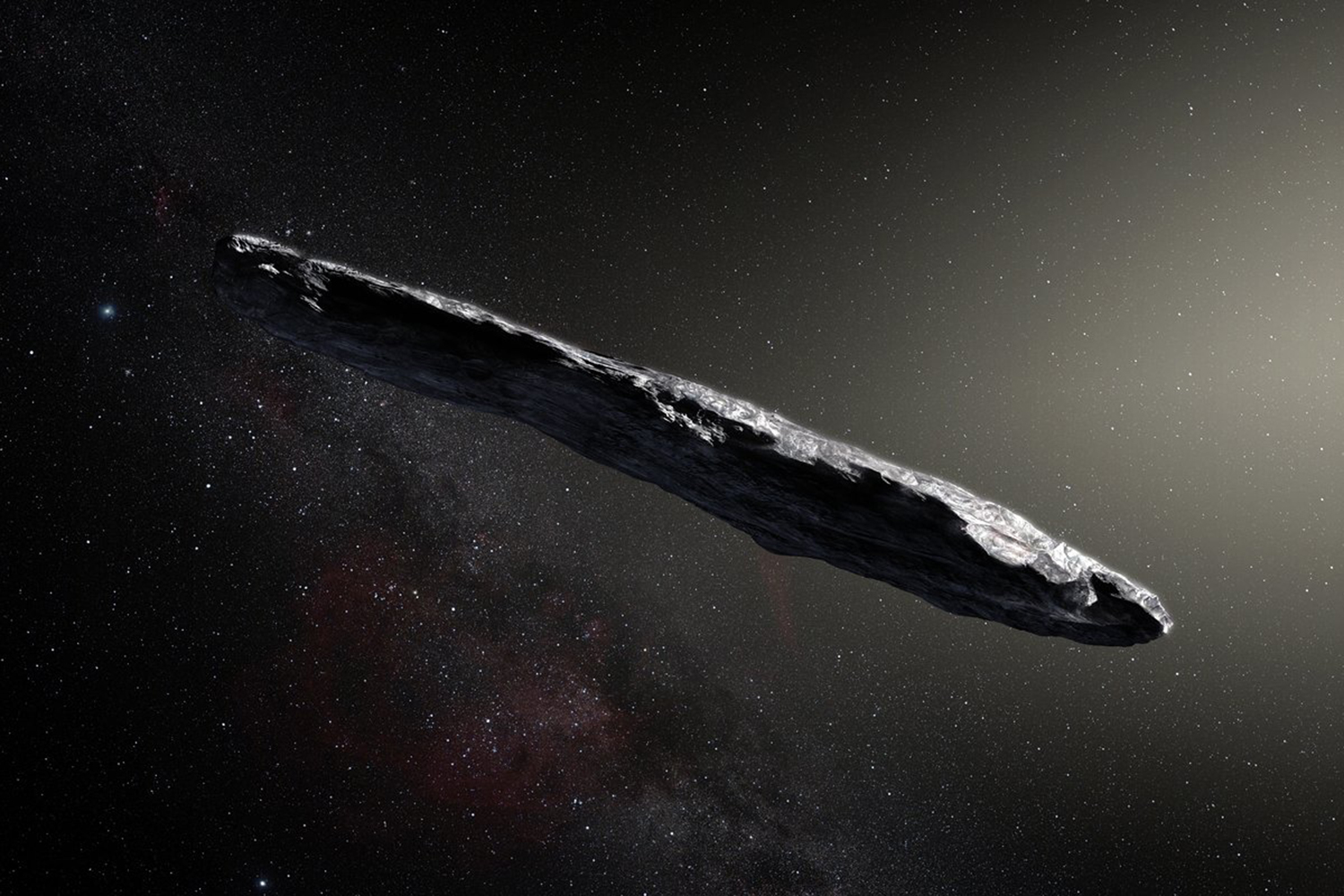

Interstellar comets like ‘Oumuamua have grabbed the public’s attention with the possibility that they could bring materials or even lifeforms from other solar systems to our own. But a new paper argues that the opposite process could be happening as well: We could be exporting life from our solar system to others via comets.

When astrophysicists have considered the distribution of life by means of comets in the past, they have generally focused on the panspermia theory, which hypothesizes that life is spread throughout the universe by dust, meteoroids, comets, and other cosmic bodies. Particularly in the case of microscopic lifeforms like bacteria or algae, they could become trapped in or on debris which is ejected into space when planets or other bodies collide, and this debris could carry them to other locations.

The new study, however, suggests that a different method could cause the spread of life: Objects which come close enough to the Earth to pick up some lifeforms from the atmosphere without actually impacting the planet.

Lead author Amir Siraj explained the problems with the panspermia approach Universe Today: “Traditional theories of panspermia posit that planetary impacts can accelerate debris out of a planet’s gravitational field, and potentially even out of the host star’s gravitational field. Among other issues, this debris is often quite small in size, providing little shielding from harmful radiation for any potentially enclosed microbes during the debris’ journey through space.”

Siraj went on to argue that the mechanism of comets grazing Earth’s atmosphere has explanatory advantages over the older theory: “One advantage of a long-period comet or interstellar object scooping up microbes from high in the Earth’s atmosphere is that they can be quite sizeable (hundreds of meters to several kilometers) and guaranteed to be ejected out of the solar system by passing so close to Earth. This allows microbes to become trapped in nooks and crannies of the object and gain substantial shielding from harmful radiation so that they might still be alive by the time they encounter another planetary system.”

The research has been submitted for publication in the International Journal of Astrobiology.