Everyone knows the Earth goes around the sun, but something you might not know is that its orbit isn’t perfectly circular. Earth orbits in a slight ellipsis, so it isn’t always the same distance from the sun: sometimes it comes closer, and sometimes it’s further away. Today, Saturday, January 2, the Earth is at its closest point to the sun, in an event called the perihelion.

At its perihelion, the Earth will be just 91.5 million miles from the sun, compared to its further point (called the aphelion, which will happen on July 5 this year) when it is 94.5 million miles away. According to NASA, the distance between the sun and the Earth varies by around 3 million miles throughout the year, which is 13 times the distance between Earth and the moon.

Alas, that difference in distance isn’t enough to bring noticeable extra warmth, so if you’d been hoping for a warm day in the middle of winter in the northern hemisphere then you’re going to be disappointed. That’s because the seasons are caused by the tilt of our planet, which is set at a slight angle so some parts of the globe face the sun more than others at different times of the year. The tilt is different from the elliptical orbit, which is why we won’t be getting warmer weather even though we’re closer to the sun.

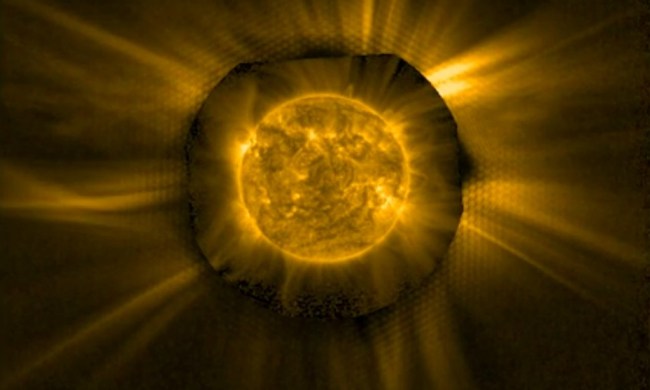

This year though we can expect to learn a whole lot more about our nearest star, with missions like the Parker Solar Probe which will be getting closer to the sun than any human-made object before to observe the sun’s corona. The probe will study the sun’s outer atmosphere to learn more about solar winds, which are streams of charged particles that are periodically released from the corona and which affect space weather.

There’s also the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter which has a camera on board to capture images of the sun directly, and which will take the closest-ever photos of the sun. Its aim is to shift in its orbit so eventually it will pass over the sun’s poles, which have never been observed before. Researchers believe that imaging the poles is essential for understanding the magnetic field of the sun.