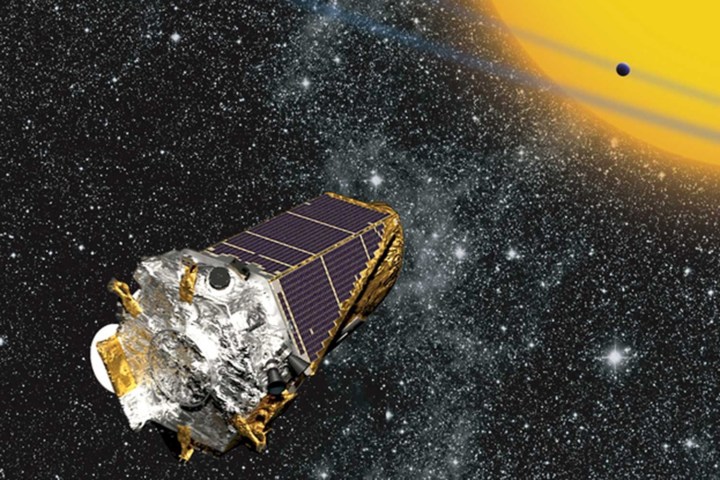

The Kepler Space Telescope may have been retired in 2018, but data from the mission is still being used to make new discoveries. Recently, an international team of astronomers used data from the mission to identify a new planet that is remarkably similar to Jupiter but is located almost 17,000 light-years away.

The planet, named K2-2016-BLG-0005Lb, was discovered by sifting through Kepler data collected in 2016. It is almost exactly the same mass as Jupiter, and it is located similarly far from its star as Jupiter is to the sun. That makes it, as the authors of the study write, “a close Jupiter analogue.”

As the planet is so far away, it was difficult to see it and its observation was only possible thanks to an alignment of a large-mass object between the planet and us. This technique is called gravitational lensing, and it allows astronomers to see distant objects with the intermediate objects acting as magnifying glasses.

“To see the effect at all requires almost perfect alignment between the foreground planetary system and a background star,” explained Dr. Eamonn Kerins, Principal Investigator for the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) grant that funded the work, in a statement. “The chance that a background star is affected this way by a planet is tens to hundreds of millions to one against. But there are hundreds of millions of stars towards the center of our Galaxy. So Kepler just sat and watched them for three months.”

The fact that it was possible to find a planet using Kepler data in this way is surprising, as Kepler was designed to find planets primarily using a different method called the transit method. This looks out for small dips in a star’s brightness caused by a planet passing between us and the star. Kepler discovered more than 2,600 exoplanets in this way during its tenure.

Regarding the latest discovery, Kerins compared Kepler to upcoming missions like NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and the European Space Agency’s Euclid space telescope: “Kepler was never designed to find planets using microlensing so, in many ways, it’s amazing that it has done so. Roman and Euclid, on the other hand, will be optimized for this kind of work. They will be able to complete the planet census started by Kepler.”

Further study of exoplanets is important not only to learn about far-off systems but also to learn about our own solar system and how planets here might have formed. With future exoplanet hunters, Kerins says, “We’ll learn how typical the architecture of our own solar system is. The data will also allow us to test our ideas of how planets form. This is the start of a new exciting chapter in our search for other worlds.”

The research has been submitted to the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is available to view on pre-print archive arXiv.org.