Update Jun 23: A NASA spokesperson has clarified that the powering down of some of the Voyagers’ systems is part of an ongoing process of power management which has ramped up in the past three years and is not a recent change. A committee will make a decision about further management of the probes’ power budget this August. The article has been updated accordingly.

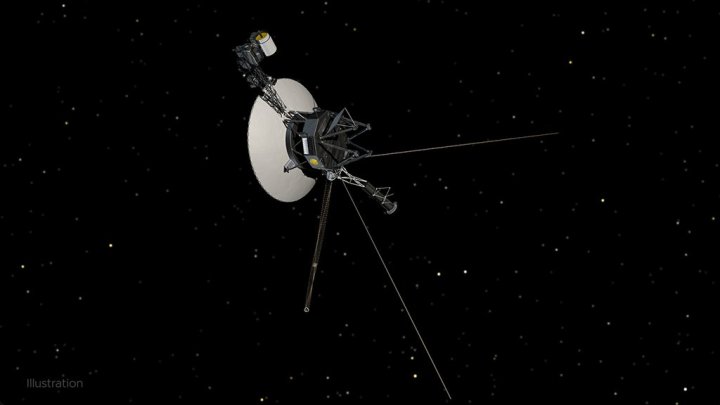

The Voyager probes, the most distant human-made objects in the universe, are entering their twilight years. The two probes built by NASA were launched in the 1970s, and their decades-old hardware is still operating — much to everyone’s astonishment — but their power levels are falling at a rate of four watts per year. Over the last three years NASA has turned off the heaters of the probes’ remaining five science instruments, but impressively enough the instruments have continued to operate even in conditions much colder that that which they were tested for.

The fact both probes are both still operating at all is incredible, given that they were originally designed for a four-year mission. “We’re at 44 and a half years,” Ralph McNutt, a researcher who has worked with the Voyager probes, said to Scientific American in a profile about the mission. “So we’ve done 10 times the warranty on the darn things.”

The Voyager program was able to take advantage of a moment of cosmic coordination, when Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune were all lined up in such a way that the probes could visit each of these planets on their one-way journey away from Earth. The probes snapped images of Jupiter’s clouds, discovered new phenomena like volcanic activity on Jupiter’s moon Io, and investigated Saturn’s rings.

But perhaps the probes’ most celebrated contribution to science was an image that recorded where they had come from: The famous Pale Blue Dot photo showing the Earth as a tiny dot against the blackness of space, taken by Voyager 1 in 1990 when it was 3.7 billion miles from the sun, beyond the orbit of Neptune. The photo has reminded scientists and members of the public of the vastness of space and the fragile nature of Earth ever since.

In 2013 and 2018, Voyagers 1 and 2 respectively passed a boundary called the heliopause and entered interstellar space. The heliopause is the edge of the sun’s solar wind, and traveling beyond it leaves the probes on the farthest edges of the solar system. The probes are still working and being used to study the interstellar gas they are floating through.

However, as you’d expect, the probes’ 40-year-old hardware has faced some issues. Voyager 2 suffered a power glitch in 2020, and just recently Voyager 1 experienced a strange error from its altitude control system. But they are both still operating and collecting and transmitting data, far outliving even the most optimistic predictions of their lifespans.

With careful power management, they may be able to continue working in some capacity until 2030 — after which we’ll have to say goodbye to these two pioneering explorers, sailing off alone into the dark.