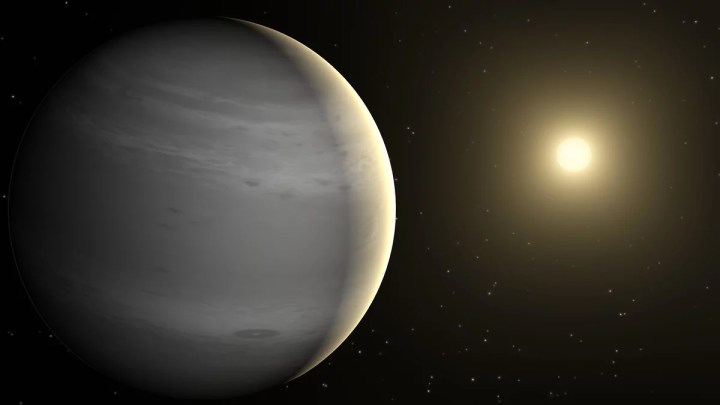

Astronomers recently discovered a hefty exoplanet orbiting a star similar to our sun. At just 15 million years old, this chunky planet is a baby by galactic standards, old, but it has researchers puzzled due to its tremendous density.

The planet, called HD 114082 b, is similar in size to Jupiter, but seems to have eight times its mass. It’s common for astronomers to discover gas giants similar to or larger than Jupiter, but it’s very unusual to discover a planet this dense and heavy. “Compared to currently accepted models, HD 114082 b is about two to three times too dense for a young gas giant with only 15 million years of age,” said lead author Olga Zakhozhay in a statement.

If the mass measurements of this planet are correct, that would make it twice as dense as Earth — and Earth is already a dense planet, being a rocky type with a metal core. It could be that because the planet is so young, there is something about the way gas giants form that we are not yet aware of.

“We think that giant planets can form in two possible ways,” Ralf Launhardt, a co-author from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, says. “Both occur inside a protoplanetary disk of gas and dust distributed around a young central star.”

The first approach to how planets might form is called core accretion, in which a small core attracts other particles, which collide and stick to it until it becomes the starting point of a planet. The second theory is called disk instability, in which there is a disk of matter that cools and then splits into planet-sized chunks.

Most astronomers lean toward the core accretion theory, but this planet doesn’t fit that model. If it were formed by core accretion, you’d expect it to start off hotter than in the disk instability model, and hot gas should puff up to a larger volume. The small volume of this planet is a better fit with the less popular disk instability model.

However, there are many open questions about how planets form and how quickly they cool after formation. “It’s much too early to abandon the notion of a hot start,” said Launhardt. “All we can say is that we still don’t understand the formation of giant planets very well.”

The research will be published as a letter to the editor in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.