Of all the big, ambitious goals in astronomy right now, one of the most exciting is the discovery and characterization of exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system. We know that there are likely as many exoplanets as there are stars out in the universe, and that this number almost certainly includes some planets which are like Earth, In fact, we’re just starting to scratch the surface of discovering these strange, new worlds.

Astronomers have tools like the cutting-edge James Webb Space Telescope to help them identify exoplanets and peer into their atmospheres, but there is only so much observing time available on these big, famous telescopes. So to help find new exoplanets, NASA is turning to an underutilized resource: citizen scientists.

A newly expanded NASA program called Exoplanet Watch invites members of the public to help observe exoplanets using the same data-analysis methods used by the professionals. To learn about how it works and the potential for discovery using this approach, we spoke to Rob Zellem of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, an astrophysicist and creator of the Exoplanet Watch program.

Amateur eyes on the skies

Given that there are now over 5,000 known exoplanets, you might think that these planets are easy to observe. But that’s not the case. Most exoplanets are impossible to observe directly, because they are so much smaller and dimmer than the stars around which they orbit. So amateur astronomers, just like the professionals, rely on indirect observations to let them know that a planet is there.

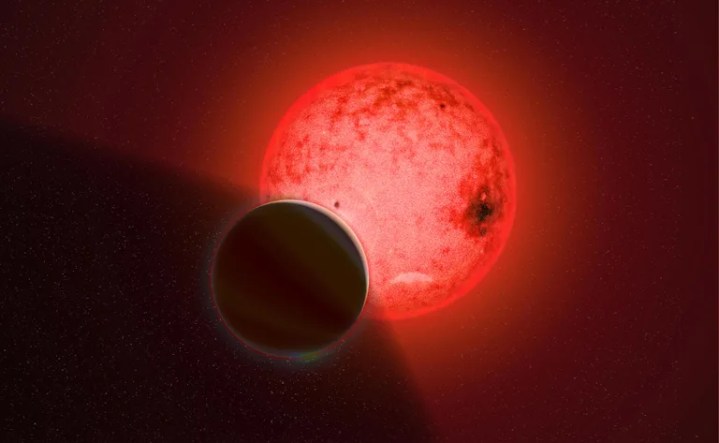

The primary focus of Exoplanet Watch is to look at a type of planet called a hot Jupiter — “big planets around bright stars,” as Zellem describes them — and observe their transits. A transit happens when one of the planets passes between us and its host star, temporarily making the light from the host star dimmer. By observing the exact timing and amount of this drop in brightness, astronomers can work out how big the planet is and how far it orbits from its star.

This is the same method used by many professional exoplanet-hunting telescopes, like NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) or the European Space Agency’s CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS). These are both space-based telescopes, meaning they get a great view of space unobstructed by Earth’s atmosphere, but observing time on them is extremely limited.

Other ground-based professional telescopes also observe exoplanets, but they face a big and unpredictable obstacle: the weather. If there are cloudy skies over an observatory, a whole night’s observations will be lost — something every professional astronomer has dealt with. “There are a lot of nights I’ve lost personally in the southwest of the United States, or Mauna Kea in Hawai’i, due to weather,” Zellem said. “That’s the risk you run by getting time on any random professional observatory.”

Exoplanet Watch, however, is a network of amateur astronomers from across the globe. By having observers taking readings from so many different locations, the effects of weather are mitigated. Even if it’s cloudy in one location, observers in other places may have a clear view.

Working together across the globe

The network also allows observation of exoplanets that would be impossible for a single user to observe. A gas giant exoplanet called HD 80606 b, for example, takes over 12 hours to transit its star. Astronomers need to not only observe the full duration of this transit, but must also take observations before and after the transit to use as a baseline, and there simply isn’t a long enough night to observe the full time anywhere on the planet other than the extreme poles.

In December 2021, members of Exoplanet Watch worked together to observe this full transit from beginning to end, starting with users in east Asia, who then handed off observations to those in India, then Europe, then North America, before going back to users in Japan.

Data from all these observers spanning 24 hours was brought together to get the equivalent data to a telescope attached to a balloon floating all the way around the world and observing as it went.

Facilitating observations by others

Zellem and other members of the Exoplanet Watch team are keen to ensure that the amateur astronomers who work on the project have their contributions recognized, and many have been featured as lead authors in academic publications about their work. But much of the work done by the project isn’t about flashy headlines like discovering brand new exoplanets — instead, it is about people selflessly donating their time and effort to enable big scientific discoveries to be made more efficiently.

Take the James Webb Space Telescope. This phenomenally powerful telescope can not only identify exoplanets, but can also observe their atmospheres, something practically no other tool in astronomy can do. But there are only so many hours in a day, and observing time is highly valued.

“We’ve had professional astronomers come to us and say, ‘Hey, there’s this target that I want to observe in the next few months with James Webb, can you help us observe this target and refine the timing?’” Zellam said.

Then the amateur astronomers in Exoplanet Watch work to find the constraints on the exoplanet transit times, so when Webb does its observations, it has the best possible chance to see the transit and get as much information about the target as it can.

“Where Exoplanet Watch comes in is by doing this pre-vetting or pre-observations. We’re helping refine the timings so we can use James Webb more efficiently and hopefully get a lot more science out of it,” Zellem explained.

Telescopes in the attic

Many of the people who have contributed to Exoplanet Watch so far are serious amateur astronomers who have spent years building up impressive telescopes and are very experienced in exoplanet observations. But that level of commitment and equipment isn’t required at all, and Zellem and the team welcome anyone who is interested in observing to join them.

The smallest telescope used in observations so far is just 3.5 inches, which is a typical size for a small starter telescope. Because most observations are made of bright objects, very powerful home telescopes aren’t essential.

“You don’t need a very large telescope to do these observations,” Zellem said. “You can actually use a lot of telescopes that people might have hanging out in their attics or their garages or their storage.”

It is helpful for observers to have a digital camera to attach to their telescope to record their observations, and a tracking mechanism to help follow a target as it moves across the sky. But the barrier for entry to the project is lower than you might imagine.

And for those who are worried about making a mistake and messing up the data, Zellam says that a strength of having multiple users is that data can be checked against other observations: “If you have one user who accidentally makes a mistake or uses the wrong values when interpreting their data, that data can be weeded out by the larger group of observers.”

Contributing without a telescope

Even those who don’t have access to a telescope at all can still get involved in the Exoplanet Watch project. A second branch of the project, in addition to the observations, is data analysis. The project has access to archival data that includes 10 years of data from a 6-inch robotic telescope, called an autonomous observatory, located in Tucson, Arizona, It has been donated by a group called DIY Planet Search.

In this data set, there are over 2,000 light curves that could be indicative of an exoplanet transit, and the public is invited to help with this data analysis. Something special about this project, though, is that it isn’t a simplified type of data analysis or classification, as seen in other citizen science projects like those on Zooniverse. Instead, citizen scientists can use the exact same data processing program used by the professionals at NASA.

Professional astronomers at NASA had already spent a decade developing and using a data analysis tool called Exotic, which was optimized to be as accurate and useful for exoplanet research as possible. “And it became very apparent that the best way to make sure our users were getting good results out of their data was to let them use the same exact data tool,” Zellem said.

The tool has been uploaded to the cloud to make it easier to access even on a mobile phone, so now anyone who has the time and the interest can learn how to process exoplanet data using the same tools as the professionals. They go through every step, from taking raw data off a telescope to determining the features of an observed exoplanet.

Inspiring the next generation

Getting help with observations and data analysis is crucial for professional astronomers, but the project also aims to bring more people into the field.

“As a citizen science project, we have science goals, but also educational goals,” Zellem said, “to inspire the next generation of STEM learners, folks that might hopefully go into astronomy.”

That includes engaging the passionate and capable amateur astronomy community, but it also involves bringing in new people who might have had little or no experience with this kind of science before.

“We’re getting people involved who have never done exoplanet imaging, never done astrophotography or even looked through a telescope,” Zellem said. The more experienced group members are teaching and guiding the newer members in the project’s Slack group, supporting each other and helping them to learn. “It’s a really great group of people, and I’m so proud of them.”

A golden age of exoplanet research

The Exoplanet Watch project is continually expanding, with new data sources constantly being added to the pool so there’s always something new for people to work on. But Zellem wants to expand it even further, pushing the limits of what can be observed with smaller telescopes.

One plan is to see whether enough small telescopes working in concert can observe smaller planets, such as those called super-Earths. Another long-term goal is to take more observations of host stars in a process called stellar variability monitoring, which can help with more precise measurements of exoplanet transits.

With more exoplanets being discovered every month, the potential for both professional and amateur astronomers to make discoveries is boundless.

“It really feels like we’re in a golden age of exoplanet research, and it’s incredible and a lot of fun to be able to work in this field,” Zellam said. “And I really do think that citizen science will continue to be a large portion of this.”