Memes don’t usually have the longest shelf life. Temporary Internet superstars like Antoine Dodson and once-popular photos like Scumbag Steve fade into obscurity and get replaced by newer, trendier memes. They’re fun, and they’re disposable. Like a Forever 21 top: Three seasons from now you’re probably not even going to remember them.

But that’s all beginning to change – and what better example is there than Grumpy Cat? The foul-tempered feline miraculously extended its run and signed a movie contract, which says way more about the state of the entertainment industry than it does about the merits of Grumpy Cat. More telling, however, is the cat’s crossover from meme to mainstream art.

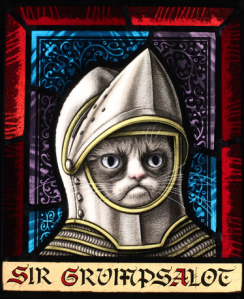

Grumpy Cat recently inspired an art exhibit with over 30 studio artists working to create Grumpy Cat-themed artwork, which was then sold at an auction out of the Lowe Mills Art Gallery in Huntsville, Alabama. The auction raised money to build a children’s playground in the area, and some of the artwork commanded impressive sums of money, especially a painted glass piece called “Sir Grumpsalot” by Judson Portzer.

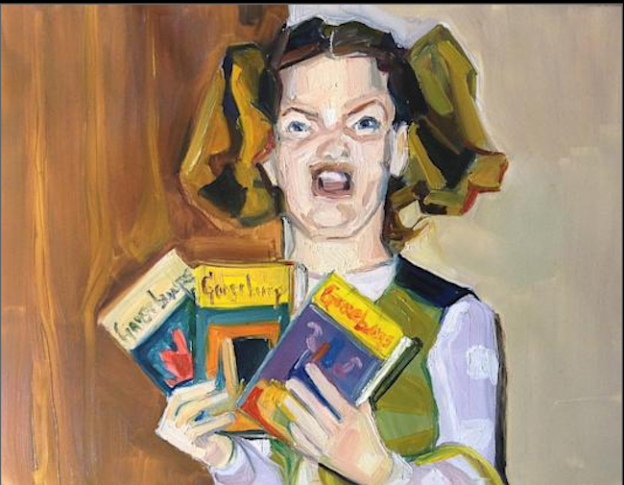

This Grumpy Cat exhibit is impressive for its thoroughness, but it’s actually not the only instance of memes as the artist’s muse. The painter Lauren Kaelin has an entire project of paintings inspired by the Internet – and while she has her own version of Grumpy Cat, she also covers countless other Web delights like Prancercise Lady, Sneezing Panda, Sloth Photo Bomb, and I Like Turtles.

Kaelin’s website displays many of her paintings (which you can buy prints of here) and explains her philosophy. She calls the project “Benjamemes” and she bases her work on both the Internet and the theorist Walter Benjamin.

“Benjamemes takes its name from a German art theorist, Walter Benjamin. In Benjamin’s 1936 essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ he addresses the then new-found reproductibility and availability of art. This democratization of art made Benjamin question the value of the original. An original of art, he theorized, possessed an aura, which made the experience of viewing the original unique. Reproductions degraded the value of the original’s aura.”

“A successful meme is by definition reproducible, shareable, and recognizable. Benjamemes creates an aura where none previously existed.”

Kaelin described how she came to memes, citing the Ikea Monkey as her first meme love. “Originally, I was just really eager to paint the Ikea Monkey: His isolation, his expression, and most of all, his jacket – all really appealed to me. When I developed the project, memes proved to be a great source material. There’s a treasure trove of past material and new Prancercises are happening all the time.”

Not all memes are created equal for Kaelin – some are too difficult to turn into art. “So far, I’ve steered clear of cartoon memes, or memes that are heavily text dependent. It’s important to me that each Benjameme stand alone as an image and to some extend, be beautiful,” Kaelin says. “So far, I’ve attempted to paint Maru and Rick-Rolled and have had a hard time with them. They ended up not looking like my style, so I didn’t post them. I’m determined to do Rick Astley, though. One day.”

The idea of communal ownership is one that meme-lovers embrace.

Kaelin’s project explicitly sets out to imbue memes with an artistic “aura” – they intend to elevate the material. And while the Grumpy Cat exhibit’s intentions aren’t as clear, the quality of the artwork demonstrates that the artists saw their project as a thing of value; this wasn’t pure kitsch. They’re creating something with a wink and nod, certainly, but it’s supposed to be (and is) good, interesting art, as well.

Kaelin’s paintings are certainly well-done and high-quality; the impressionistic, angular style has all the marks of a professional painter’s work. She takes memes and transforms them into something more.

And this memes-as-muse trend isn’t limited to just the Grumpy Cat exhibit and Kaelin’s art. There are many galleries showcasing Internet-based art. One of the more prominent ones, Gallery 1988, which refers to itself as the world’s number one destination for pop-culture art, has run exhibits that Kaelin’s paintings would fit into well. A 2012 exhibit called “Memes” draws from similar source material, with art depicting Honey Badger, Hipster Ariel, First World Problems, and other popular Internet touchstones.

Of course, “good” is an entirely subjective and often fraught concept in the arts, and there may be critics who deride the choice of subject matter here – although probably not as many as you might think, since this type of artwork owes a debt to Andy Warhol and other pop artists who took the banal and everyday and brought it into the fine art world.

These productions aren’t stuffy or pretentious – they’re for the people and by the people; the democratization of art without rules and ample creative license.

The PBS Idea Channel recently discussed the idea of memes as art. “Here’s an idea – anyone who has made a LOLCat has also made a work of art,” host Mike Rugnetta says. “People are creating images and sharing them with strangers to communicate their personal experiences? That, my friends, is art.” Although he allows that not all philosophers would agree, Rugnetta uses statements from thinkers like Tolstoy and Aristotle, going so far as to argue that Rage Comics embody Aristotle’s idea of art as catharsis.

Commentators like Rugnetta and artists like Kaelin make a strong case for memes as capable of hinting at the sublime, even if Kaelin takes some extra steps to isolate the meaningful elements and use her skill to raise her source imagery into something more beautiful.

But this isn’t a one-way street. Memes can blur the line between content and art, but certain pieces that begin as art can also take on the qualities of a meme. For instance, much of Banksy’s work – though it starts as street art in alleys, on billboards, and on the sides of buildings – has become a staple of Internet imagery. The impact of the piece of art is not lost in reproduction; it is meant to be shared, and as Omar Canosa writes, “Banksy’s artwork explicitly and repeatedly proclaims his disdain for the concept of copyright or artistic ownership.” The idea of communal ownership is one that meme-lovers embrace.

To bring everything full circle, more traditional art can become a meme as well – just look at what happened with Ecce Homo, the Spanish fresco that began as art, but after a ridiculously botched restoration, became a meme.

As you can see, most of the artful qualities were obliterated in the restoration, and the Internet quickly embraced the art tragedy as a meme windfall. Parody Twitter accounts were made, people started calling it “Potato Jesus,” and something called The Cecilia Prize was established to recognize the most comical and inventive re-interpretations of the image. The creativity was endless.

So basically, Ecce Homo (the meme) is the opposite of what Kaelin is achieving with her artwork. The Ecce Homo meme is making the best out of a situation that’s actually kind of sad (destroyed art) but it would probably be difficult for even the most open-minded art critic to categorize some of the entries as art, since their intention is obviously just a lighthearted joke and they’re not actually meant to evoke emotion, just viral, share-worthy hilarity.

Memes and Internet culture are fertile ground for artistic sparks. It’s less obvious that memes are art on their own merits, but because there is no objective criterion, it’s impossible to discount them as creative, valuable digital artifacts at the bare minimum. These productions aren’t stuffy or pretentious – they’re for the people and by the people; the democratization of art without rules and ample creative license.

The haters who see Lil Bub gear and Nyan Cat paintings as tacky gimmicks are always going to hate – but they’re also going to increasingly find themselves in a world enjoying and adoring this “art” … or whatever you want to call it.