In the battle for dominance in American sports, the NFL is Achilles – a great warrior destroying all challengers. It eats up the largest percentage of coverage on SportsCenter. Through July, all 10 of the year’s most watched sporting events were NFL games. Among the world’s 50 most valuable sports franchises, 30 come from the NFL. Fantasy football, a massive driver of interest in each week’s games, is a billion dollar business with over 32 million players. According to one estimate, the near-constant search by the American worker for injury updates and waiver wire diamonds costs the economy upwards of $6.5 billion a year.

But even great warriors aren’t without weakness; Achilles had his heel.

The NFL has the head.

Awareness of and sensitivity towards concussion and other forms of mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) has skyrocketed in the last decade. The league has overhauled its concussion protocols, implemented several significant rules changes designed to protect a player’s head, some more enthusiastically greeted by players and fans than others, all done in the shadow of recently settled litigation by over 4,500 former players against the NFL who say the league misled them about the dangers of head injuries and their cumulative effects. Several high-profile suicides among former players have shined a light on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a degenerative brain condition many believe contributed to their deaths. The president himself has questioned whether, had he any sons, he would allow them to play football.

The NFL doesn’t get much bad press. This would be an exception.

Increased attention to head injury — not simply in pro football but in college and high school, and across other sports — has prompted serious growth in the development of technologies in impact measurement, sideline diagnostic tools, and systems designed to gather badly needed data about MTBI; sophisticated weapons to fight an important enemy. So how quickly could they make the NFL a (relatively) safer place?

Really, it depends on who you ask. The league, like any massively powerful industry generating billions in revenue, has its own political ecosystem, one littered with obstacles. There are legal questions and scientific hurdles; questions of collective bargaining, public perception, and the league’s motivations and track record. One final complicating factor? The players, who suit up every day balancing concerns about their future health against current priorities of competition, playing time and financial reward.

For them, the integration of cutting edge technology related to head injuries isn’t necessarily an unqualified good.

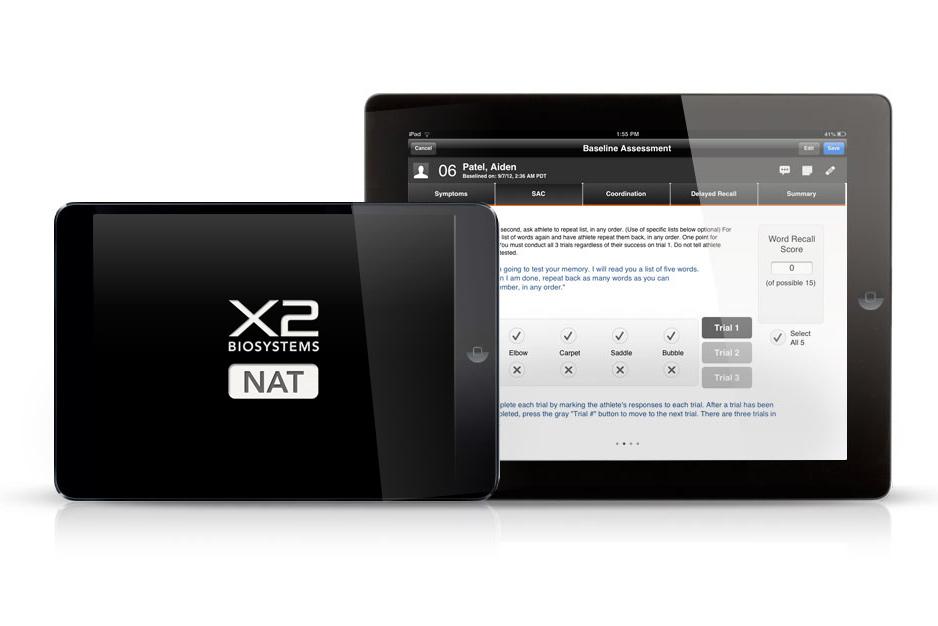

A first line of technological defense against concussion is the neurological assessment tablet app developed by Seattle’s X2 Biosystems. Like traditional pen-and-paper baseline tests it scores players on criteria including confusion, dizziness, memory, and concentration, but adds a much deeper level of sophistication based on a player’s personal history with concussion. The longer a player interacts with the assessment tool, the better.

For the players, integration of cutting edge technology related to head injuries isn’t an unqualified good.

“We have tracked that individual over time to figure out what would precipitate another such event and what, if any, are the differences in the recovery profile. Does it take longer for individuals to recover from the second, third or fourth diagnosed concussion than their first? Do players that have a history of concussions early on, are they more susceptible to it as they age? And what kind of risk factors contribute?” says Christoph Mack, CEO of X2.

That information is available for every player, easily referenced in a tablet display. Traditional “baseline” assessment tests still exist — an athlete’s “normal” still requires measurement – but Mack calls the X2 software “fundamentally easier, faster, more efficient, and more consistent than the paper and pencil baselines that they replaced.” Clearly the league agrees. After running a pilot program last season with half the NFL’s 32 teams, in 2013 every squad will use the X2 software.

Still, while better assessment tools are unquestionably valuable, at the NFL level it’s the technology still on the metaphorical sidelines offering the greatest potential for sea change in the recognition, diagnosis, and understanding of brain injury in football.

Sensor technology makes it possible to measure and record every impact a player absorbs in practice and games.

Riddell, the NFL’s official helmet sponsor (though players may wear any brand and model meeting certification standards), has developed a helmet-integrated system called the Sideline Response System (SRS), which includes their HIT (Head Impact Telemetry) technology, currently designed to fit into a pair of helmets in the company’s line. SRS measures both linear and rotation acceleration, noting the severity, frequency, and location of head impact through six sensors embedded in a removable helmet insert. Should any particular impact exceed a pre-determined threshold based on factors including a player’s position, age, and concussion history, sideline staff are notified wirelessly.

SRS has been in use for nearly a decade, building a database of approximately two million recorded head impacts. Fundamentally, the system operates today in the same way it did at inception: Impacts are measured by the sensors, converted by custom algorithms into data revealing location and head acceleration, then transferred wirelessly by Mx encoders inside the helmet to a sideline console. By developing a protocol in which the signal consistently dances over a 900 mz frequency band, Simbex, Riddell’s partner in the development of SRS, was able to avoid interference sending the data to the proper recipient.

Riddell has its own proprietary software suite — cleverly named “RedZone” — allowing team trainers and doctors easy access to a player’s medical history and baselines. Users collect the data, synchronize to a central database, and then have access access to it on the sideline through the cloud. Similarly, X2 has developed it’s own “X-Patch,” a quarter-sized sensor weighing just two grams and worn behind the ear. Using a miniature triaxial accelerometer and gyroscope, the patch measures the impact parameters of every blow, including linear acceleration, rotational acceleration, location, and direction of the incoming impact. That information stored in a Windows Azure cloud database, then sent over a proprietary, encrypted, online banking-style secure wireless system designed to guarantee a player’s impact and medical information doesn’t go to the wrong sidelines.

On a larger scale, it’s not the technology itself but the data – information already collected and still to come — offering the best opportunity to mitigate the effects of concussions on the sport. Everything improves, says Jonathan Beckwith, Director of Research at Simbex. “We have made improvements to equipment, improvements to the evaluation of the equipment, developed new test procedures to evaluate the equipment, and rule changes have been developed to better match the information we’ve recorded on the field,” he says.

From there, he notes, data allows clinicians to better understand and anticipate head injury, collectively and even by position. For example, Beckwith knows exactly what the average offensive lineman’s impact profile looks like and how it differs from, say, a cornerback. The third prong? “Evaluation,” says Beckwith. Every change in the equipment’s engineering, every rule adjustment, can be measured for effectiveness.

X-Patch and SRS aren’t diagnostic tools; they’re data collection devices. But used in concert with truly portable head assessment technology, they could create a far more fully protective umbrella in which medical staffs are alerted to significant impacts in real time, then look inside that player’s brain without leaving the sidelines or relying on more subjective, interview-style tests. Moreover, they might provide the promise not only of diagnosing concussion, but the absence of it as well, which is a key component in safely clearing players for competition.

“That’s really the holy grail, not just for X2, but for everybody involved in this effort,” says Mack. “They want to be able to see the injury response in the brain in real time.”

That reality may not be far off.

Mack predicts this sort of technology will “rapidly evolve over the next couple years,” pointing to BrainScope as a company that has created a handheld device essentially performing the functions of an EEG without requiring the giant EEG machine. BrainScope is being developed primarily for use by the Department of Defense to quickly detect brain injury and concussion in soldiers on active duty.

Sports, though, are certainly on their radar.

At UC-Berkeley, researchers led by Dr. Boris Rubinsky are developing a similarly portable, non-invasive “halo” capable of matching the diagnostic abilities of a CT scan. Essentially, using wireless technology, low energy electromagnetic waves are sent through the brain by a pair of coils inside the device, measuring changes in conductivity to detect changes in the brain (say, concussion). Like BrainScope, the technology (called Volumetric Electromagnetic Phase Shift) was originally conceived as a diagnostic tool for individuals outside sports – in this case people without easy access to hospitals – but applications for competition are obvious.

In theory, the device could allow physicians to monitor a player’s brain in real time.

Rubinsky’s team submitted a proposal – one of over 400 from more than 25 countries – to the NFL through the GE-NFL Health Challenge, a four-year, $60 million collaboration aimed at developing technologies to “speed diagnosis and improve treatment for mild traumatic brain injury.” Additionally, the NFL has made a $30 million grant to the National Institutes of Health helping facilitate research capable of better protecting both athletes and non-athletes alike.

From any number of organizations and in a variety of forms, the science of head safety is attracting serious investments in money and brainpower.

This season, X2 is supplying over 3,000 sensor systems to prominent institutions including Michigan, Stanford, Washington, Wisconsin, and Nebraska, for use not only in football, but lacrosse, soccer, and field hockey. Riddell’s technology can be found at about 20 NCAA programs, including Virginia Tech, North Carolina, and new this season, Southeastern Conference football power Georgia. However, save X2’s assessment software, none of the products mentioned to this point has penetrated the NFL. Given the level of scrutiny aimed at the league and pressures to improve player health and safety, deploying cutting edge tools seems like a (wait for it…) a no-brainer.

Not necessarily.

While the NFL has aggressively implemented rules changes, they have by comparison been more conservative with technology. As one source who has worked with the league puts it, “NFL researchers don’t want to get out over their skis.” A level of caution is reasonable. Good research is a slow process, and putting the wrong devices on NFL sidelines could lend a false sense of security or expose players to other dangers. No small consideration, ethically and legally. But the league, whatever its record on head safety, is only half the equation. The players themselves play an equally significant role, and integrating technology in ways satisfying both parties hasn’t been easy.

Kevin Guskiewicz, professor of exercise and sports science at the University of North Carolina and member of the league’s Head, Neck, and Spine Committee, has researched the Riddell SRS system for nearly a decade with the Tar Heels football program. He told ESPN’s “Outside the Lines” there is no reason it couldn’t be adopted for use in the NFL.

“That next play … could get me millions of dollars, and now I’m sitting here because all I needed was two aspirin?”

The NFLPA did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The logic is legitimate. The union could reasonably object to affording extra protection only to a limited portion of its membership. Moreover, players have developed a healthy skepticism, often well-earned, for those claiming to protect their best interests, whether coaches or the league. Hines Ward, who won two Super Bowls with the Pittsburgh Steelers over a 14-year career, expressed concerns about how the data would be used during games, but also who might have access to it during contract negotiations.

“If ownership looked at that (data) and said, “Look, this guy has had head trauma,” and that cost me millions in a short span of an NFL career, I wouldn’t want to do that at all,” he told ESPN.

Ward’s comments point to an important duality for NFL players. There is certainly an increased awareness of the impact repeated MTBI can have both during and after his career. Players are also acutely aware of how short that career can be. Less than four years, on average, and unlike the NBA or Major League Baseball, contracts are not guaranteed.

Players want to play, win, and make whatever money they can. For many, long term health can be a secondary consideration.

Marcellus Wiley, a Pro Bowl defensive lineman who played 10 years before retiring in 2006, explains the mentality. “If a guy says I’m good, and the test says, “No, you’re not,” now you’re getting into legalities and protections to save you [from potential liabilities], not save me,” he says. “You’re going to take opportunities away from me to make my money, to make my mark? That next play, which could be a sack, forced fumble, big-time situation could get me millions of dollars, and now I’m sitting here because all I needed was two aspirin?”

Even if properly armed with the best science available, the calculus of future health vs. present opportunities remain. Last year, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Alex Smith was having the best of his seven seasons as a pro when he suffered a concussion in Week 11. Smith himself reported symptoms to the team’s medical staff, was pulled from action, and never regained his starting gig.

Colin Kaepernick led the Niners to the Super Bowl, and will try to do it again this season.

Smith says he doesn’t regret self-reporting, and while last year’s concussion problems almost certainly cost him money, he’ll still make $8.5 million this year after an offseason trade to the Kansas City Chiefs.

But for every Smith who has the luxury of knowing more work is around the corner there’s a third string linebacker and special teams player for whom every training camp could be his last. For that guy especially, sensors and diagnostic machines could become the enemy.

“In the end, the power of technology is in how you can change behavior,” says Isaiah Kacyvenski, a Harvard grad who played seven seasons in the NFL before joining MC10, which partnered with Reebok to create the Checklight impact indicator a skullcap utilizing a green/yellow/red LED system to alert coaches and medical personnel of a potentially dangerous blow, while tracking a players impact load over time. “At the moment of truth, can you see this change in behavior where the athlete keeps their head out of impact?”

Kacyvenski believes Checklight’s testing record indicates the answer is yes, because the product reinforces proper tackling technique. Sensor data, he says, not only provides incredibly valuable information in the battle to understand concussions, but adds one more way for individual athletes to understand what they do with their heads during competition.

The best treatment for a concussion is not to sustain one. Better technique can’t fully prevent them, but can unquestionably drive down the numbers.

But for all the advancements in hardware and software, much of the player safety equation remains decidedly low tech. Rules changes and discipline for dangerous play are means of decreasing injury through behavior modification, though the consistency of officiating and the league’s messaging on big hits has significant room for improvement. The league hopes players, understanding the potential dangers, won’t push through symptoms of MTBI.

“Education and awareness,” says NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy, “is important.”

To that end, the league developed a program pairing players with members of the military who have experienced mild traumatic brain injury. The goal? Reinforcing the wisdom not only of a player removing himself if he feels symptoms present, but watching closely for signs in others.

Another key factor is time. As more players grow up in an age of concussion awareness and an amateur sports world with brain monitoring and sensor data, getting yanked from a game for head injuries won’t feel much different than a bad ankle or knee. A level of trust, or at least normalcy, develops in technology and its influence.

But reducing the incidence of head injury, particularly at the professional level, requires one more significant change. Players can mind technique and adjust accordingly to evolving rules. That’s learned behavior.

“The second part of it, which is probably more important, is what’s rewarded?” Wiley says. “Once a guy does it the right way, if you overlook him for a guy who just laid the big hit, then you’re rewarding the wrong guy.” That means changing what plays are celebrated on Jumbotrons and highlight packages, then playing/paying the guys who do it right, even though “right” won’t look as sexy on TV.

And ultimately, it means accepting football at any level, and certainly the NFL, can never be made truly safe. No matter the level of good intentions and technology, people will get hurt, sometimes badly. There will be consequences long after a player shelves his shoulder pads for good.

“On the football field, you’re not thinking this guy is 310 pounds and runs a 4.7, 4.8 40-yard dash and is about to knock my head off. You’re thinking ‘What am I going to do to him?’ Not “What am I going to do to my body?” Wiley says. “The game happens so fast. If (the running back) is running by me, I would love to put my head in the proper place. I would love to wrap him up. I would love to do all the things I saw in the textbooks. But right now, I just saw a calf muscle and I stuck something out there and I saw what happened.”

“The game won’t ever change in those respects. We’re trying to move the bell curve, the middle, to a better place, but there’s still going to be those edges, brother.”

Disclosure: Digital Trends’ Chief Marketing Officer is on the X2 board of directors