Here’s how it works: A child is asked to play Angry Birds as a robot closely observes where the child’s finger starts and stops, what ends up happening on the screen as a result, and the success of each attempt as measured by the on-screen score. When it’s the robot’s turn, it mimics the child’s movements. If the bird-flinging is unsuccessful, the robot will shake its head in disappointment; if an attempt is successful, its eyes light up and it celebrates with a cheerful sound and dance.

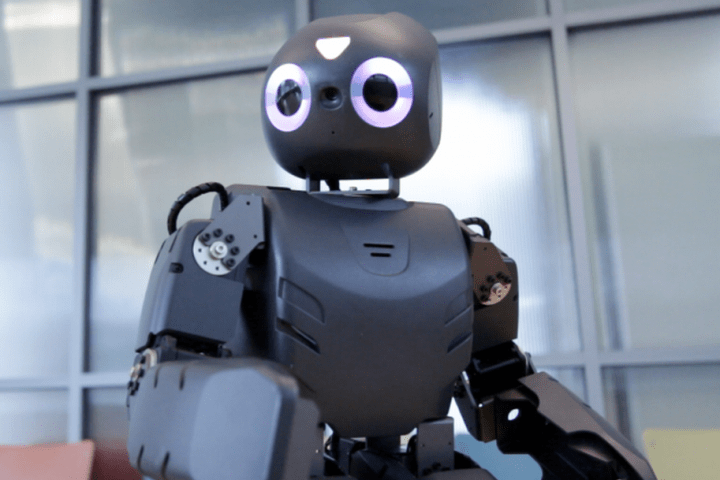

The robot (which should really have a catchy name) analyzes information, adapts its behavior and provides what it deems to be appropriate social responses, a set of actions that would make it useful in real-world scenarios. For instance, the robot would be a helpful rehabilitation tool for children with cognitive and motor-skill disabilities, according to Georgia Tech researchers.

Once the robot is programmed by a clinician to help a child with, say, hand-eye coordination tasks, it can be sent home with the child. For one thing, the robot would have more patience and energy than a parent would for such a repetitive string of tasks. The child would also be more inclined to be more engaged in their rehab session if the robot is involved.

“Imagine that a child’s rehab requires a hundred arm movements to improve precise hand-coordination movements,” says Ayanna Howard, Motorola Foundation professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Georgia Tech and the leader of the project. “He or she must touch and swipe the tablet repeatedly, something that can be boring and monotonous after a while. But if a robotic friend needs help with the game, the child is more likely to take the time to teach it, even if it requires repeating the same instructions over and over again. The person’s desire to help their ‘friend’ can turn a five-minute, bland exercise into a 30-minute session they enjoy.”

Howard and Hae Won Park, a postdoctoral fellow working on the project, conducted a study that found that children spent an average of nine minutes with Angry Birds when an adult was watching. When the robot was watching and learning how to play the game, children spent an average of 26.5 minutes – nearly three times as long – playing the game. Also, the children in the study spent 7 percent of their session having eye contact with the adult observer, a number that jumped to 40 percent with the robot.

The team of Georgia Tech researchers plans to include Candy Crush and ZyroSky in the next stages of the project. They’ll also involve more children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and children with motor impairments.

From teaching kids basic programming skills, to acting dull to help children learn English, robots are becoming more prevalent in the learning and development of future generations.