“You just keep shooting, and hope for happy accidents. The first editing process is actually in the camera.”

Electronic music icon Moby has always put forth an individualist’s spin with his music, and he carries that philosophy over to his acclaimed photography. Even after countless high-profile exhibitions and gallery shows, he still adheres to the advice his uncle Joseph Kugielsky, a photographer for The New York Times, shared after bestowing him with one of his old Nikon F cameras when he was just 10 years old.

“He said, ‘If you can, take pictures of things other people can’t see,’” Moby recalls. “If you’re a tollbooth worker, take pictures from inside your tollbooth; no one else can see that. If you’re a musician, take pictures from onstage, because no one else can see that. Given the ubiquity of photography, especially in the digital age, I feel almost everything has been shot 100 million times.”

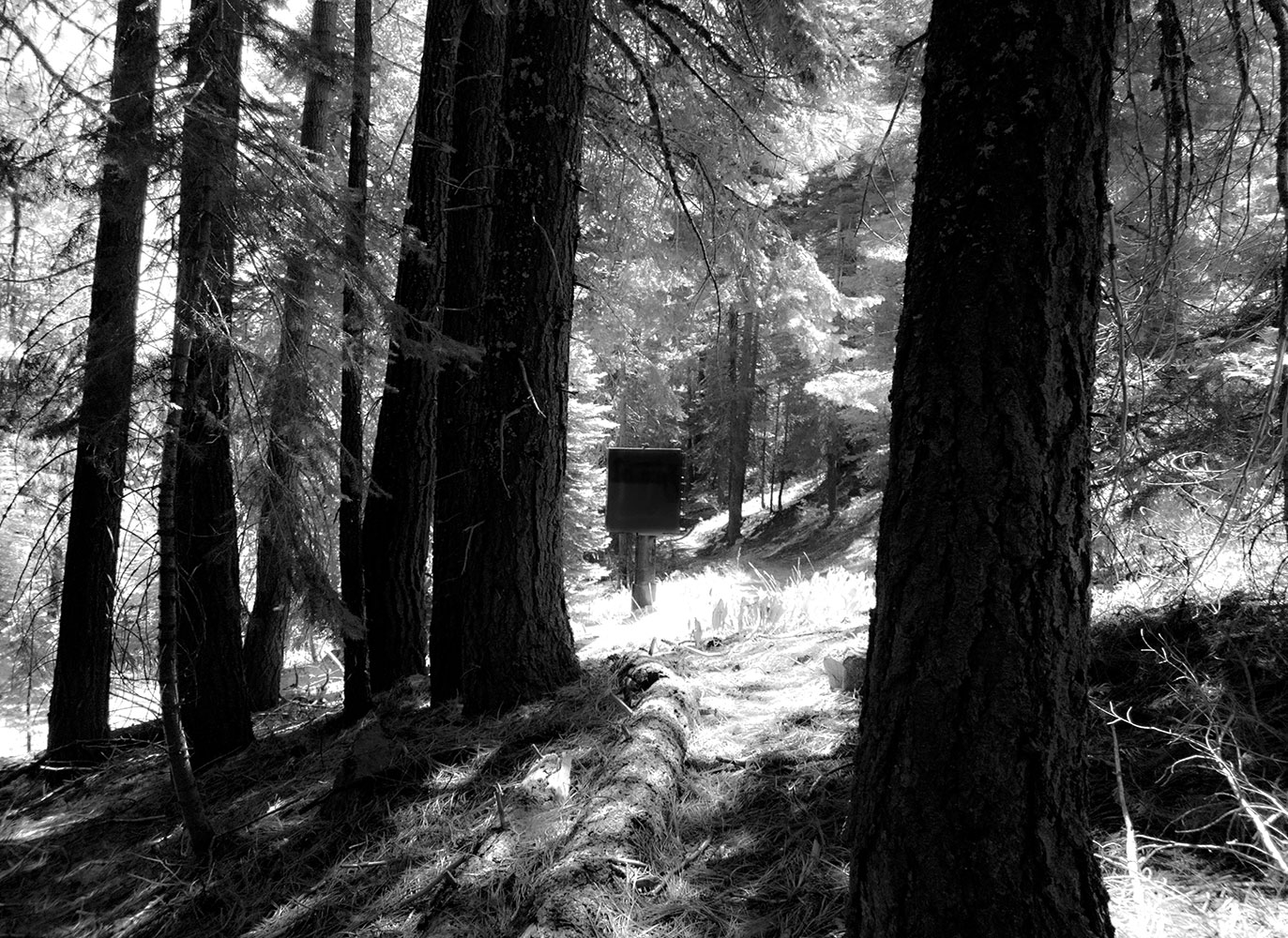

That digital ubiquity has affected Moby’s creative impulses. “Considering half the people on the planet are taking pictures, it’s the question of what I can do as a photographer that might have meaning to me and other people and still somehow be unique,” he observes. “As time passes, I’ve become less interested in reportage and documenting with what’s already there. The Innocents show was me creating a world and then documenting it, almost sort of manipulating the semiotic relationship people will have with an image.” Innocents, Moby’s successful 2014 gallery show, was based on the idea that “the apocalypse has already happened. The show is a look at the apocalypse and a post-apocalyptic ‘cult of innocents’ that has arisen in the wake of the apocalypse.”

Digital Trends called Moby (real name: Richard Melville Hall) in Los Angeles to find out more about how he first got into photography, what his favorite gear is, and what he’s going for when he takes pictures while performing onstage. One thing’s for sure: Moby likes to shoot.

Digital Trends: When did you first know photography was important to you and was something you wanted to pursue?

Moby: Growing up, I was first introduced to serious art photography through my mom. We were very poor, and we only had one art book while I was growing up – a book of Edward Steichen photos from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. I spent my childhood repeatedly looking at this Edward Steichen book (on pictorialism) and being amazed by it.

What fascinated me about photography, even at an early age, was understanding how this medium could have so many different utilities. Photography is so ubiquitous. It could be used to sell butter, it could be used to demonstrate war atrocities, and it could be used to create very subtle, nuanced beauty. I thought that was so interesting, and totemic, and powerful.

My uncle (Joseph Kugielsky) had been a photographer for The New York Times, so I grew up hanging out with him in his darkroom. He would take me to photo shows at the ICP (International Center of Photography), in New York and other places.

“Because I was very poor, I had to shoot very, very selectively when I was growing up.”

Photography is literally in your blood, I guess you could say.

Yeah. When I was 10 years old, he gave me my first camera, a Nikon F that he had used for years and years. In hindsight, it really was an ambitious, aspirational camera for a 10-year-old who had never really taken pictures. And then every year for my birthday or for Christmas, I’d get another piece of photo equipment.

What would you get – things like new lenses?

I always had the same lens, but I got a spot meter. When I was 13 or 14, my uncle loaned me some old darkroom equipment he wasn’t using – an Omega D2 enlarger. I set it up in the basement of my mom’s house and started learning how to mix chemicals and process film, develop, and print.

The only thing I don’t miss about the darkroom is the chemicals, because they really were incredibly toxic. When I spent a lot of time working in darkrooms, I would just feel sick all of the time. Especially the fixer and the stop baths — I feel those two chemicals in particular have probably taken years off my life.

What are you using now, gear-wise?

Well, it depends what I’m shooting. If I’m shooting something more formal or more considered, I use the Canon EOS 5D Mark II. But I have a Canon PowerShot that I use for things that are more spontaneous, like if I’m taking pictures onstage or if I’m doing underwater photography. I’ll use the Canon PowerShot because it shoots RAW. Even though it’s a small camera, I’ve actually been able to take pictures with it and print them really, really large – which surprises me, because I assumed with small cameras, I’d have inherent limitations in terms of what I could do, printing-wise.

Because I was very poor, I had to shoot very, very selectively when I was growing up. Film was expensive, chemicals were expensive, developing paper was expensive – everything was expensive. When I started shooting digitally, I started shooting the same way I did with film – very selectively and very sparingly. But over time, especially with shooting onstage, I just let myself shoot constantly.

How do you know when you want to take a shot when you’re performing? How do you get into that frame of mind?

As far as choosing what to shoot – because the lights are changing so quickly, you can’t really anticipate, even from one second to the next, what you’re going to get. So you just keep shooting, and hope for happy accidents.

For me, the first editing process is actually in the camera. When I’m in my hotel room after the show, before I put the images of the audience into Lightroom, I will look through the camera and try to delete half of them. A lot of times, half of them will be too dark, or too blurry, or something.

Do you have any particular favorite happy accidents?

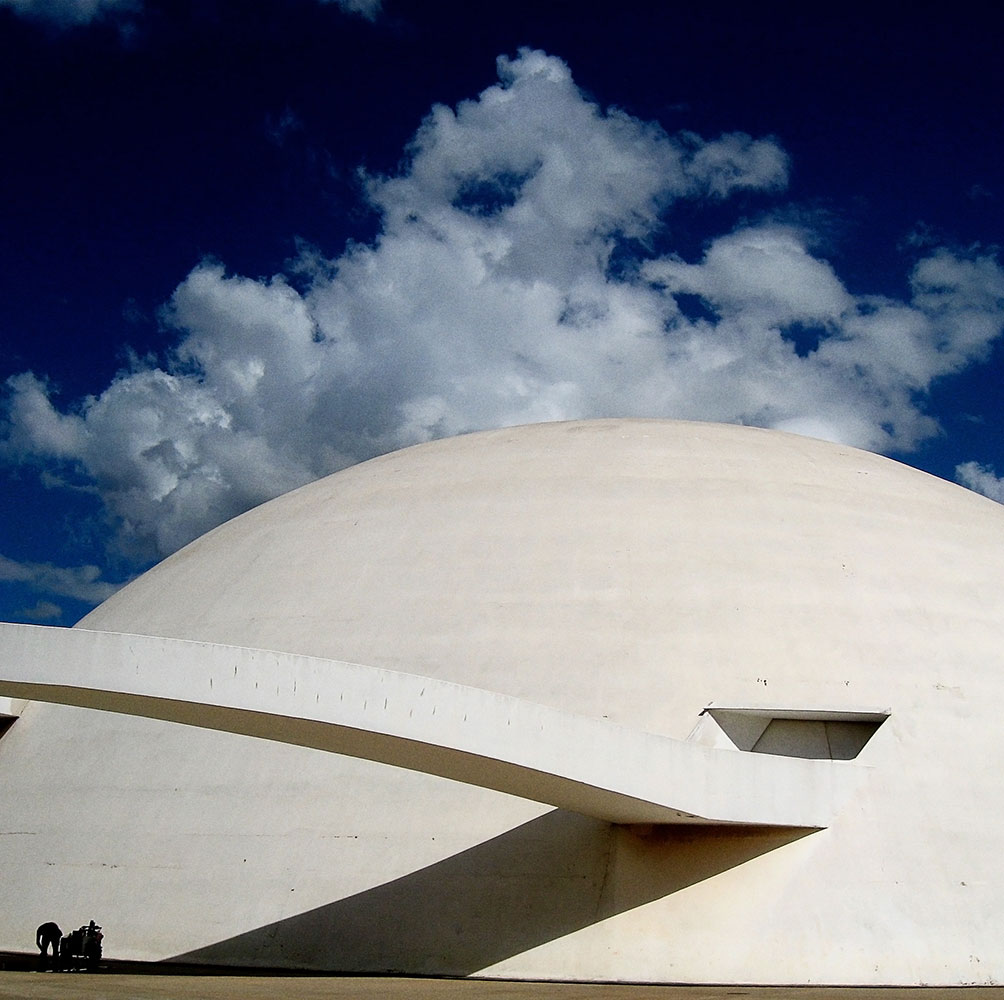

“It’s OK to not take any more pictures of the Eiffel Tower.”

There are certain things that don’t need to be shot again, especially by someone who’s been trying to be a thoughtful, professional photographer. You can just leave certain things alone. Like the Eiffel Tower – it’s OK to not take any more pictures of the Eiffel Tower. I mean, it’s a beautiful building, it’s remarkable, it’s iconic, but unless you can bring something new to a photograph of something that’s been shot a million times, it’s probably best to just move on and find something other people haven’t documented.

There is a unique style for shooting onstage and on the road.

I wouldn’t even know what to call it – it’s sort of that hybrid between (pauses) … autobiographical reportage. One of my favorite bodies of work is Richard Billingham, a book called Ray’s a Laugh (published by Scalo in 2000). His dad’s name was Ray, and it’s this amazing document of a family raised in a Northern England housing estate. On the surface of it, you couldn’t imagine anything less dramatic or compelling than an alcoholic living in a depressing housing estate. But in the hands of the photographer Richard Billingham, it becomes beautiful and transcendent and heartbreaking, and able to communicate these truths about the human condition. That’s his genius in that body of work, taking the utterly mundane and capturing it and presenting it in a way that’s unique and beautiful.

And that’s key. Could it also be done with the Eiffel Tower?

Yeah, there’s probably a photographer out there as we speak who’s taking a picture of the Eiffel Tower and capturing it in a way that’s absolutely new and unique.

Is there some subject or object that you consider as a challenge, something you’d do something new with in a way it hasn’t been done?

Honestly, it was done in the book Destroyed (2011), the document of going on tour. The truth is, the world of musicians going on tour has been documented a billion times. But I realized almost every document I’d ever seen of a musician on tour started to look the same to me: either glamorous pictures of the musician onstage, gritty black-and-white pictures of a musician backstage, or musicians on a private plane – and always informed by a sense of glamor.

Glamor and entitlement.

Yep. The experience of touring – there’s very little that’s actually glamorous about it. Even if you’re in an ostensibly glamorous environment, it’s still generally pretty not glamorous. I wanted to document the disconcerting strangeness of touring, the “mundanity” of touring in a way I’d never seen before. That was the challenge right there – to document touring in a way that felt idiosyncratic and honest.

“Being these weird, multi-cellular creatures – in and of itself, that’s strange.”

I like that. When you go on the road – and I’ve been out there with bands myself – there are 20 or more hours in the day that are not the glam that some folks make it out to be. Speaking of that, I love the one shot you took of the people waiting at the airport.

Mm-hmm. It’s one of the reasons I became friends with Jason Reitman after he made Up in the Air (2009), because I think he did such a great job of showing not just the lack of glamor around air travel, but that disconcerting strangeness. Doing any sort of travel and any sort of touring, at the end of the day…it’s just weird.

Travel is an odd thing in some ways, if you step back from it. Does it ever get any less strange, the more you wind up doing it?

The familiar can feel less strange over time, but then it’s sometimes nice to take a step back and almost reacquaint yourself with the strangeness of the familiar. There isn’t really much in anyone’s life that, when examined, doesn’t reveal itself to be strange. Everything is.

Even just the very act of being alive is strange, in a universe that’s 15 billion years old on a planet that’s 5 billion years old. Being these weird, multi-cellular creatures – in and of itself, that’s strange. By definition, there are lots of things in our lives that are familiar, but that doesn’t in any way diminish their strangeness.

Innocents was a huge success. Do you have any other big umbrella photo projects you’re working on now?

No. There’s a lot of information to process and respond to, and I’m in the process of trying to figure out what that next photo project and photo show will be.

One of the amazing things about photography – and I’m completely stating the obvious – is it can be anything. I’m speaking specifically about static photography; two-dimensional unmoving photography. A lot of my friends who are photographers are moving into experimental films and making movies. I like doing that, but ultimately, I still see so much power in a static, two-dimensional image. It can be abstract, it can be hyper-real, it can be reportage, it can be completely fantastical, invented, and made up. There’s something both liberating and daunting in trying to think of the next weird photo project I do, because it can be anything.