We’ve heard this tune before, from a different manufacturer. HP performed the same trick with its Spectre, cramming up to an Intel Core i7 processor in the self-titled “world’s thinnest notebook.” In fact, almost every major laptop release of 2016 has decided to ditch Core M – and for good reason.

Slower, but not less expensive

Intel had big plans for Core M when it launched in 2014. It was built in response to the perceived need for a fast, power-sipping chip for 2-in-1 devices. At the time, PC builders had to choose between Atom, which was way too slow for top-tier systems, or Core, which inflated system size due to its power draw (and the need to exhaust the resulting heat).

Intel crippled Core M from the start by slapping high prices on the hardware.

Core M’s position between the two made sense, in theory. But Intel crippled it from the start by slapping high prices on the hardware, a practice that continues to this day. The Core M3-6Y30 has a stated customer price of $281. The Intel Core i5-6200U has an identical recommended price – but it’s much quicker.

Of course, users don’t pay that price. It’s absorbed by PC builders like Asus and HP, who factor it into product pricing. Some of it is passed on, however, which means consumers find themselves picking between Core and Core M at the same price point. The latter just can’t keep up.

The limits of portability

To make matter worse, Core M didn’t deliver the portability expected — or rather, devices based on it didn’t. Our reviews have consistently found that systems with a Core M chip offer middling endurance. The longest-lasting notebooks have Core i5 and i7 chips.

It’s a physics problem. Core M let PC builders design thinner systems, like Apple’s MacBook. But a PC’s dimensions decide the size of the battery it can contain. Smaller PC, smaller battery, less energy. So while Core M uses less power, what’s gained in efficiency is lost in battery capacity.

That makes the chip’s downsized performance an even harder sell. A fancy new 2-in-1 may be lighter, but if it lasts no longer away from a socket, does its smaller size matter? Consumers don’t seem to think so. There seems a point where further reducing a notebook’s profile isn’t a boon. And we may already be past that point.

Branding baloney

Intel used its Computex keynote to announce that its two next-gen platforms, Apollo Lake (Celeron and Pentium) and Kaby Lake (Core) are on-track. The company didn’t say anything about Core M.

The average person doesn’t understand why Core M exists.

Architecturally, that makes sense. Core M uses the same basic silicon as Core, so when Intel says “Kaby Lake,” it’s talking about both. But Core M is also a distinct brand from Core, built for radically different devices. The brand names of Core i3, i5 and i7 are supposed to be immediately identifiable as separate from Core M, but the average consumer doesn’t understand that, or why M exists. Those who are aware of it at all simply know it as “the slower one.”

Intel should’ve used a different name for Core M, one that’s not linked to Core. It would make the difference between them easier to explain, and it would discourage comparisons that always put Core M in a bad light. Alas – hindsight is 20/20. At this point, Intel seems committed to its branding.

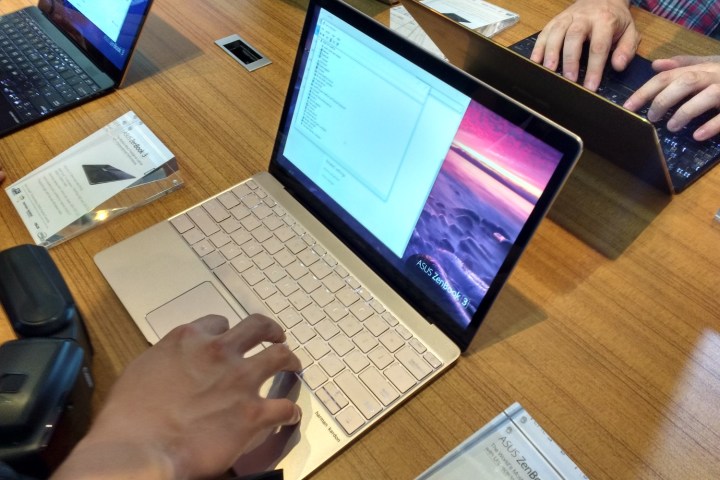

Core M may not last long

It’s hard to see how Intel can save Core M. The big PC builders never adopted it in significant numbers, and those who did embrace it are turning away. Asus’ decision not to use it in the Zenbook 3 is particularly damning. This is the company that built the best Core M ultrabook in the world – the Zenbook UX305CA – and sold it for $700. Yet even it decided to use Core in its news flagship.

And time is not on Core M’s side. Intel’s processors are always becoming more efficient. Eventually, the standard Core will become so efficient that there’s no point to building a separate, low-power brand. The next major production process leap, due in 2017, could be the end of the road.

Don’t get me wrong. Core M is mere speed bump on Intel’s road forward. But its lack of success offers insight into what people want from notebook. In 2014, it seemed they were merging into tablets. Today, that point is debatable. Super-thin designs aren’t winning when they sacrifice battery size and speed for style and versatility.