Old orbiters, pieces of disused rockets, and countless fragments from past space-based collisions are all orbiting Earth, presenting unwelcome dangers for those aboard the International Space Station (ISS), as well as future space missions. On top of that, there’s also the risk of costly crashes with working satellites, which in turn would create even more hazardous space junk that could then collide with other debris to create even more trash. Yes, the situation is at risk of spiraling out of control.

A myriad of solutions to clear up the trash are being examined, from lasers to solar-sail “parachutes” to targeted air puffs designed to force the junk to de-orbit and burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.

Another idea is the work of the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), which in the next few months will try for the first time to steer a piece of simulated space junk toward Earth’s atmosphere, forcing it to burn up.

The simple and relatively low-cost method, which has been in development for several years, creates a powerful magnetic field using a 700-meter-long cable made with thin, super-strong, and ultra-flexible metal fibers. In theory, the technology should be capable of shunting debris through space by creating a magnetic force against its direction of travel, the Japan Times reported this week.

If JAXA can accurately control the trash’s movement, it’ll be able to push it toward the Earth’s atmosphere, where it’ll quickly disintegrate. The junk-busting technology will be transported into space aboard Japan’s Kounotori 6 cargo transporter later this year, and the trial run will take place after it’s delivered supplies to the ISS.

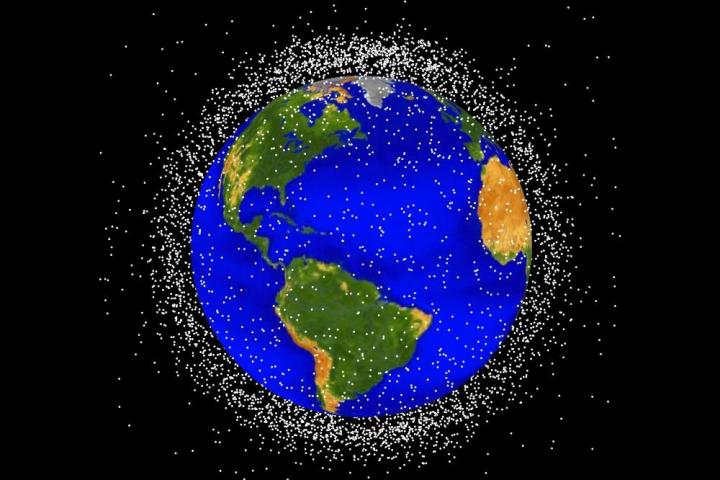

A reliable solution for clearing up space debris can’t come soon enough. NASA believes there are currently 500,000 pieces of space debris the size of a marble or larger, and 20,000 pieces bigger than a softball – easily big enough to cause serious damage to working satellites or even the ISS if a collision occurred.

The fact that all this space junk has accumulated in just 60 years of space travel highlights the seriousness of the situation, and if you can’t quite imagine just how much is out there, check out this stunning, though rather alarming, visualization created last year by Stuart Grey for the Royal Institution of Great Britain.