Technology is a wonderful thing, especially when it comes to cars. We wouldn’t have gotten from Daimler and Benz’s three-wheeled, one horsepower wagon to the Bugatti Veyron or Chevy Volt without finding new ways of making things work. However, just because an idea is new, or technically possible, that doesn’t mean it is good or practical. Here are five automotive technological dead ends.

Technology is a wonderful thing, especially when it comes to cars. We wouldn’t have gotten from Daimler and Benz’s three-wheeled, one horsepower wagon to the Bugatti Veyron or Chevy Volt without finding new ways of making things work. However, just because an idea is new, or technically possible, that doesn’t mean it is good or practical. Here are five automotive technological dead ends.

Nonetheless, carmakers have continued to experiment with different types of steering. The designers of the Baker and Detroit electric cars (built in the early 1900s) used tillers, but not because they hadn’t been able to test drive the Benz. Rather, their decision was based on marketing.

Electric cars were marketed to women, primarily because their husbands didn’t want them driving too far unescorted, and the cars had pitiful ranges. The manufacturers were on the same page: They felt that the thing women loved doing most was socializing, not driving, so they arranged their car’s interiors like a lounge. Tiller steering allowed the female driver to face her passengers.

Alternative steering didn’t die with women’s liberation. Saab, the car company that was “Born From Jets,” made a prototype with joystick steering in the early 1990s. The Honda EV-STER concept is also steered with sticks. Still, it seems like wheels are the best way to steer earthbound vehicles.

The Tucker also featured a windshield that was designed to pop out of its frame in a crash, protecting occupants from glass shrapnel. Unfortunately, the car was never mass-produced; an SEC investigation and the subsequent unraveling of Tucker’s finances became the subject of the film Tucker: The Man and His Dream. The widespread use of shatter-proof laminated glass in car windshields made Tucker’s pop-out windshield unnecessary anyway.

There has been no shortage of cars with four-wheel steering. Honda equipped the 1987 Prelude with four-wheel steering, and it became a must-have feature on the high-tech Japanese sports cars of the 1990s. The Mitsubishi 3000 GT, Nissan Skyline GT-R R33 and R34, and the Nissan 300ZX all had it.

GMC also offered four-wheel steering on its Sierra Denali full-size pickup truck from 2002 to 2004.

So why doesn’t every car have four-wheel steering? Probably for the same reason most cars do not have four-wheel drive, despite the extra traction it offers. Adding hardware to steer the rear wheels adds complexity, and cost, to a vehicle. People might not want to pay extra for systems that, admittedly, offer less of a concrete benefit than one might think.

Car companies haven’t given up on the idea, though. Acura will include four-wheel steering on the base, front-wheel drive version of its upcoming RLX sedan.

These cars worked the same way steam locomotives do. Water was heated in a boiler (usually by burning kerosene) to create steam, which pushed a piston connected to the car’s wheels.

Steam had some advantages over internal combustion. Steam engines didn’t reek of gasoline, and didn’t need to be cranked to get them started. Most importantly, steam was a familiar technology; in the 1900s it was viewed the same way gasoline is viewed today when compared to hybrids.

However, steam had far more drawbacks than anything else. Steam cars may not have needed a crank handle, but they took a long time to get going. Imagine waiting for a giant tea kettle to boil every day before your morning commute, and you’ll get the idea.

Since most steam cars had no electrical accessories, every part of the complicated starting process, from pumping fuel to opening valves to regulate pressure, had to be done manually.

Steam cars also had to be driven carefully, too. Range was dependent on the amount of water in the tank, so it varied with ambient temperature. Drivers would also have to coast whenever possible to build up a head of steam. Maybe today’s fluctuating gas prices aren’t so bad.

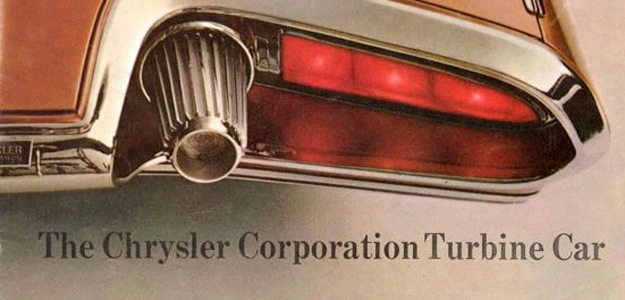

Chrysler decided to try building jet powered car in 1963, when it commissioned Ghia to build 55 bodies to house these futuristic powertrains. The Chrysler Turbine Cars were then leased to customers for evaluation, just like 21st century EVs and fuel-cell vehicles.

The Turbine Car was an impressive machine. It idled at 8,000 rpm, above the redline of most piston-engined cars, and could do 0 to 60 mph in 5.5 seconds. It could also run on any flammable liquid, from perfume to tequila.

It may sound like the silver bullet of alternative powertrains, but the jet engine simply isn’t meant for automotive use. Jets are not as responsive as piston engines; drivers of the Chrysler would notice significant lag during acceleration. Mashing the throttle actually made the car go slower, it simply could not be rushed.

Jets may also be too exotic for the road. The Turbine’s performance was impressive, but a Chrysler equipped with a relatively small 318-cubic inch V8 could match it. Jaguar thought about using micro gas turbines to generate electricity in its C-X75 supercar, but it has switched to a 1.6-liter gasoline inline-four, which can apparently do the job just as well.