Computex hasn’t been short on big announcements in computer hardware. Intel, AMD, Nvidia, and Qualcomm all had new chips to show off, and there’s plenty of reason to be excited about the new performance potential in these chips.

However, as important as shrinking processor die sizes and increased core counts are, Intel and Qualcomm spent more time talking about connectivity than speeds and feeds. After all, when the majority of laptop usage is on the web, lack of hardware performance and poor connectivity don’t feel all that different for the average person.

Two sides of the same coin

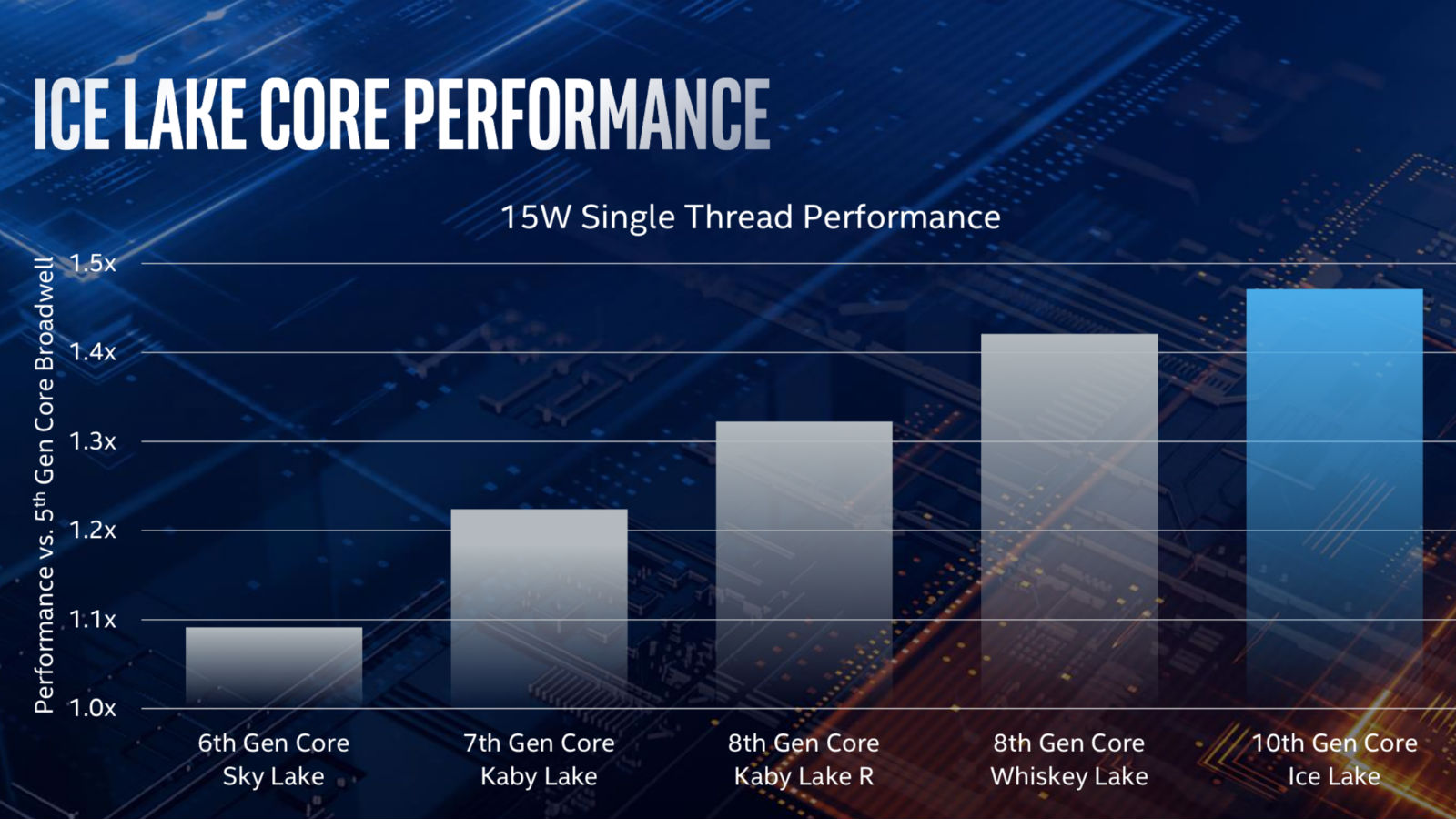

Both Intel and AMD unveiled major die size shrinks and respective new generations of processors making their way into devices. For AMD’s desktop chips, it’s as early as July, while Intel isn’t far behind it with major laptop vendors including their Ice Lake chips in time for the 2019 holiday season.

But if you strayed not too far from the two behemoth keynotes, you probably noticed far less emphasis on raw power and much more buzz around the long strides in laptop and 2-in-1 wireless connectivity slated for late 2019 and just beyond. This week, Microsoft’s blog noted the Wi-Fi 6 capabilities built into machines as different as the new MSI GT76 Titan and the HP EliteBook x360 1030 G4. Intel also put out a press release this week to tout the Wi-Fi 6 integration that its 10th-generation Ice Lake processors ship with.

And, in a bid to upstage both Intel and AMD, Qualcomm put connectivity front-and-center in its joint endeavor with Lenovo. The undertaking, Project Limitless, teases the world’s first Snapdragon 8cx-powered and, crucially, 5G modem-equipped laptop. The project has quite a sales pitch to live up to, but for Lenovo and Qualcomm to kick off an industry-wide race toward light, fast, hyper-connected 2-in-1 devices, it doesn’t really have to.

A good amount of spotlight is clearly shining on network connectivity, which may leave a lot of people wondering, “what happened to performance?” But in the current technological landscape, squeezing out more raw horsepower is not able to push the technical limits as much as it used to (at least for the moment). The two main factors that go into this is photo-lithographic engineering’s higher-stakes game of chicken with the end of Moore’s Law, and the industry-wide backtracking that chip makers are hastily executing to address the major hardware vulnerabilities discovered just over a year ago.

For a while, the industry had cried wolf about reaching the breaking point in Moore’s Law. It’s the idea that the number of transistors that can fit in the same sized integrated circuit doubles about every two years, but it seems like it might really be the end this time. Intel may stave it off for a bit longer with the nifty 3D photo-lithography trick it developed for its Foveros design, but technology probably can’t stay on the complacent side of the development trend for much longer. In navigating the uncharted waters of this new, un-Moored era of computing, speed boosts are going to have to come from somewhere other than the CPU core count.

Actually, chip manufacturers might have plenty to work on before then, because the fallout from the Spectre and Meltdown speculative execution hardware vulnerabilities doesn’t show any sign of abating. In fact, a new variant, dubbed ZombieLoad, was discovered just this month. With new proof of concept exploits still cropping up, the architectural overhauls needed to mitigate speculative execution bugs and reacquire the performance we are accustomed to may take several years and product cycles.

5G and Wi-Fi 6 take the stage

Far from just giving manufacturers a trail to blaze, rather than ground to retread, connectivity holds the potential of delivering the next generation of speed. 5G is making big waves right now — and for good reasons, not the least of which is the quantum leap in transmission speed that it will bring. Rollout might be closer or farther off depending on where you are, but whenever it reaches you, it will bring the base speed you can expect of devices with a 5G modem up to 50Mbps, with maximum speeds exceeding 1Gbps.

Not to be outdone, Wi-Fi 6 also promises to turbocharge upload and download rates, and is poised to make it to consumers much sooner than 5G. Not only does the Wi-Fi 6 spec, with its MU-MIMO setup streamlining antenna broadcast and reception interchange, reach minimum speeds of around 100Mbps on crowded networks, with the 250Mbps to 1Gbps range easily within reach of average broadband customers, but there are already routers on the market that employ the standard. Until the wave of planned laptops this week, the problem with tapping into Wi-Fi 6 speeds has been that there haven’t been devices that can communicate with Wi-Fi 6 routers in that spec.

From online games to web applications, we spend the majority of our time on our PCs connected to the internet. The reduced latency that these technologies will afford consumers, once fully deployed and available to the masses, is no incremental increase, either.

Anyone who has ever looked at their machine’s CPU usage will tell you it is waiting around for instructions most of the time. For the most part, it has been lagging network connections that have bogged down our computing experiences, not processor speeds. A concerted effort to speed up those connections will feel an awful lot like a boost in performance.

When viewed against this backdrop, connectivity upgrades aren’t so much a detour from performance improvements as they are a direct route to it. With most people more likely to enjoy faster computing experiences on account of more efficient network standards and snappier networking hardware, maybe chip makers are right to focus on connectivity.