Being the underdog has its benefits. AMD’s been running on the sheer momentum of its uphill battle against Intel — and it’s been working.

Over the past seven years, AMD has gone from being a second-rate CPU builder, only judged by its undercutting of the competition from Intel, to an absolute titan. Each generation, it has consistently released some of the best processors money can buy, and even when Intel bites back, AMD holds strong.

But this year, things feel different. Ryzen 9000, the company’s latest chips, feel apathetic by comparison. It feels like a range of products we’d see from a company that has nothing to lose. It feels like Intel — and not in a good way.

Seven years of fighting

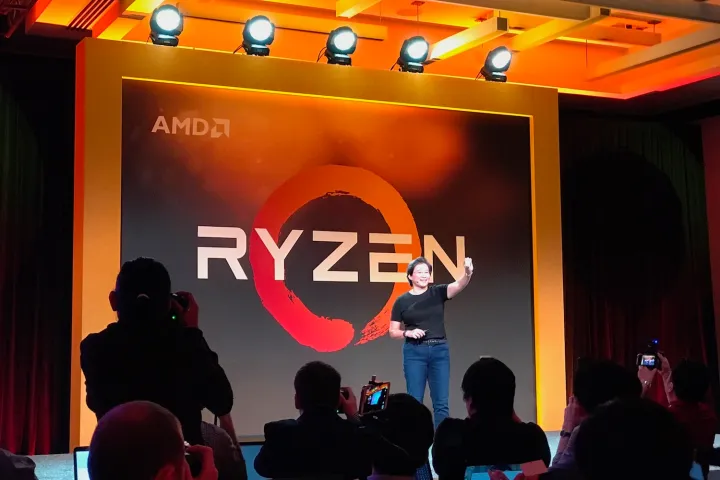

We need to back up to early 2017, when this journey all began. AMD was on the cusp of unleashing its Zen microarchitecture into the world. It was something completely different from Team Red, and it was a shake-up that the company needed. Prior to Zen, AMD had been refining its Bulldozer microarchitecture for six years — an architecture that nearly bankrupted the company. The focus on Zen was per-core performance, in contrast to the multi-threaded angle of Bulldozer variants in years prior. Instead of being the budget alternative, AMD wanted to go after Intel’s crown.

And it worked. AMD originally targeted an Instructions Per Clock (IPC) gain of 40% with Zen, and it achieved a 52% IPC gain when the design was finished. There were still kinks at launch, but Ryzen was an undeniable success.

“For years, Intel has spoon-fed us incremental improvements to their architecture, especially on the power efficiency side, claiming that their processors are reaching the climax of what is possible for x86 power-wise. Then in comes AMD Ryzen with a much lower R&D budget and at least matches and sometimes beats Intel power efficiency, often delivering better performance at the same time,” wrote TechPowerUp in its review of the Ryzen 7 1800X.

Oh yeah, Intel. The backdrop of Zen was Intel’s apathetic approach to CPUs. Years passed, generations launched, and Intel delivered about a 5% increase in performance per clock cycle with each new batch of CPUs. AMD didn’t know Intel would settle into this cadence — work on Zen started in 2012 — but it was sure ready to capitalize on a market that was fed up from getting the same side step processors that Intel put out each year.

You don’t have to take my word for it, either. In 2016, prior to the launch of Zen, AMD commanded just 9% of the desktop CPU market. According to the latest numbers from Mercury Research, it now holds nearly 24% of the market. Some even suggest AMD is more recognizable than Intel is in 2024.

AMD got there by consistently releasing excellent products while Intel struggled to drum up a new game plan. Ryzen 2000 launched in 2018 with the Zen+ design, optimizing the original core. Ryzen 3000 came a year after that with Zen 2 and cemented AMD as a market leader. And then Ryzen 5000 showed up two years later and put AMD at the top of the gaming stack with processors like the Ryzen 7 5800X3D.

Reviews at the time of the original Zen launch read like prophecy: “With the release of the new Ryzen processors, a new era begins for AMD. It brings the company back to competitiveness against behemoth Intel. Whether Ryzen is for you or not, this restored rivalry will benefit us all, be it through performance, features, or pricing,” TechPowerUp wrote.

Competitiveness returned, which is something that we’ve witnessed over the past few years. Intel got its act together and brought out Alder Lake to compete with Ryzen 5000. Then AMD fired back with Ryzen 7000, which remained competitive through Intel’s 13th-gen and 14th-gen CPUs. There are standout CPUs like the Ryzen 7 7800X3D if all you care about is gaming, but for the past few years, it has been an open question if AMD or Intel is better.

Two factors

That brings us to today and the release of Ryzen 9000. AMD quoted an IPC gain of 16% compared to the previous generation, which seems downright laughable when you compare it to the 52% we saw with the original Zen microarchitecture. And even by the standards of today, with slowing innovation in the world of desktop processors, the new Ryzen 9000 CPUs only provide a marginal increase over their last-gen counterparts.

I’ll never criticize a new architecture. It takes years — literally hundreds of thousands of hours — to design something like Zen 5 in Ryzen 9000. And with smaller nodes taking longer and longer to produce, designers today don’t have the easy wins like they did back in 2017. AMD can’t deliver the massive increase in performance we saw seven years ago, even with all of the intention in the world to do so. But there’s still a level of status quo that AMD is settling into, similar to what we saw with Intel.

That mainly concerns AMD’s 3D V-Cache. It’s no secret that the extra cache is a huge asset for PC gaming, and we’ve seen with processors like the Ryzen 9 7950X3D that AMD is able to deliver productivity prowess and gaming performance in equal amounts. AMD has also shown how 3D V-Cache benefits its Epyc server CPUs, showcasing how the tech can benefit workloads beyond gaming.

And yet, it’ll be several months before we have 3D V-Cache versions of Ryzen 9000 CPUs. We saw even in the last generation how Zen 4 CPUs struggled to get off the ground before their 3D V-Cache versions arrived. Now, with Ryzen 9000, we’re seeing a repeat. I wouldn’t be convinced to buy a new CPU if I knew a better version was coming in a matter of months.

Up to this point, Intel hasn’t had a clear answer for 3D V-Cache. It’s AMD’s secret weapon right now, which gives it an undeniable lead in gaming performance compared not only to the competition from Intel, but also AMD’s main range of CPUs. With the lukewarm reception of Ryzen 9000, I have to wonder if this level of segmentation within AMD’s lineup makes sense. Would it be better to just have 3D V-Cache chips from the start?

The other factor at play is pricing. AMD is no stranger to quickly dropping prices on the CPUs it releases, so much so that it actually lowered the recommended price of all Ryzen 9000 CPUs to better reflect how much they’d actually cost at retailers. AMD vastly reduces the prices on last-gen components, too, which has led to a situation with Ryzen 9000 where you’re almost always getting more bang for your buck by picking up a last-gen chip.

Intel has done this plenty of times in the past, and we most recently saw it with 13th-gen and 14th-gen CPUs. With 14th-gen only offering minor performance gains, it made more sense to buy a 13th-gen chip at launch because of their lower pricing.

Only one generation

Ryzen 9000 is only one generation, so it’s impossible to say that AMD is settling into the status quo like Intel did for so many years. The signs are certainly there, though. With a drip feed of 3D V-Cache, disappointing generational gains, and a pricing situation that makes the latest chips simply a bad value, a new AMD generation today doesn’t mean the same thing it has for the past seven years.

Maybe AMD is holding out for something better. Maybe, by the time we see Zen 6, it’ll continue delivering big generational increases with a range of CPUs that can hold their own for at least two years (AMD’s usual release cycle). The company has described Zen 5 as a new foundation for its CPUs moving forward, so that’s not out of the question.

Until then, AMD is caught in a difficult spot. The flagship Ryzen 9 9950X trades blows with last year’s Core i9-14900K, which doesn’t bode well considering Intel’s Arrow Lake CPUs are arriving in short order. And lower down the stack, AMD’s own last-gen options provide similar performance, sometimes better gaming performance, and come in at much lower price. Ryzen 9000 is an odd blip from a company that has maintained a near spotless record over the past seven years. Hopefully, it’s just a bump in the road and not the new normal for Team Red.