HDR has been a confusing topic, especially when it comes to computer displays. Few have the contrast or brightness to really experience true HDR, and operating systems have rarely known what to do with it.

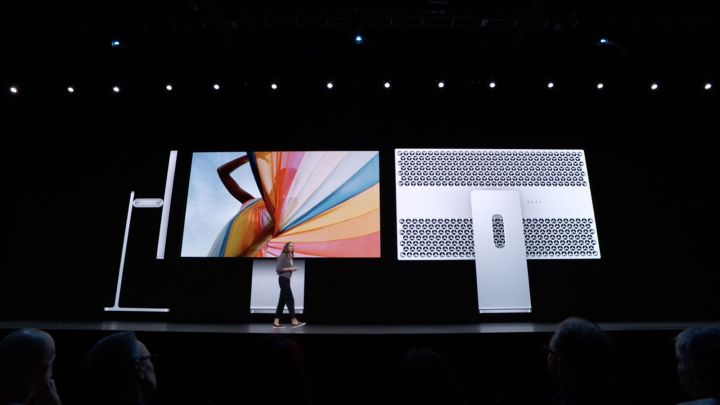

So when Apple came out with its new Pro Display XDR monitor at WWDC 2019, which promises contrast and brightness never before seen outside a high-end Samsung television, it had our attention. Six million pixels spread across a 31-inch screen for a total of 218 pixels-per-inch, sustained 1,000 nits of brightness, and 1,000,000:1 contrast — it’s all a bit insane. According to Apple, it’s so advanced that it needed a new label. XDR, or Extreme Dynamic Range, is what it’s called.

That all sounds impressive on paper, but how significant is it really?

XDR versus HDR

Comparing the Pro Display XDR to a standard monitor is an exercise in futility. Not only is it five times the price of a really expensive monitor, it’s also considerably more ambitious. That’s why Apple started by positioning it against pro-quality reference monitors, which can cost as much as $43,000. They weren’t kidding. With a similar 32-inch display size, we found a 31-inch TV Logic 4K Reference Master Monitor with Stand at Adorama that retails for $32,395 and delivers comparable features to Apple’s panel. Then again, it doesn’t feature a 6K resolution and results in some extreme heat and sound output.

“So our goal, it was simple: Make a display that expertly delivers every feature the pros have asked for,” Tim Cook’s team said of the Pro Display XDR in Apple’s WWDC keynote. “And it’s the most incredible panel we have ever made.”

But when it comes to what this monitor can actually do, we have some serious questions. In creating its XDR display, Apple claimed that it has improved on HDR technology by building the largest Retina display that it’s ever created. HDR is the standard the entire industry uses; Apple claims it has outdone them all. So what makes “XDR” so much better than standard HDR? Well, the monitor can sustain display brightness of 1,000 nits – compared with the roughly 350 nits you’ll get on a typical desktop monitor.

Even the iMac display, one of the brightest computer displays you can buy, is just over half the brightness of this new Pro Display XDR. Brightness is supremely important in a screen because the HDR effect can’t really be felt on dimmer screen.

The VESA DisplayHDR 1000 specification requires only 600 nits of sustained brightness and 1,000 nits of burst brightness. Apple’s XDR mode creates a screen that’s at least 60 percent brighter than the DisplayHDR 1000 standard in both instances. Because no monitors (outside the mentioned reference models) actually reach 600 nits of sustained brightness, they have to fake it to try and output HDR content — or at least pretend to mimic the effect. Even most LED television sets won’t be able to approach the contrast ratio promised by the Pro Display XDR.

“HDR is a way to bring content to life by better reflecting what the eye can see in the real world,” Apple said in its demo. “And the eye can see the brightest specular highlights, really dark blacks, vibrant, rich colors, and all the details in between.”

Contrast is another piece of the puzzle. Some high-end televisions (and even some computer displays) have switched to OLED, a type of screen technology that uses no backlighting at all, meaning you can turn a pixel off completely. The result is extremely deep blacks and game-changing contrast. How then did Apple achieve a contrast ratio of 1,000,000:1 on the LED-based Pro Display XDR? Apparently, by redesigning both the LED backlighting and the heat regulation.

Rather than use white LEDs, Apple used an array of 576 blue LEDs to amp up the brightness and a timing controller applies a massive algorithm to control and modulate each LED based on the content. The timing controller controls the LED at ten times the refresh rate of the LCD itself to reduce latency and ensure smooth playback with color accuracy.

“Then, we use custom lenses and reflectors to actually shape and precisely control the light,” Apple continued to explain during its WWDC keynote. “Now, a typical thermal system would make this impossible to achieve for more than a few minutes.”

To overcome that feat, Apple equipped the rear of the Pro Display XDR with a perforated pattern, which it calls a lattice design, to act as a heat sink and double the surface area for cooling. The result is that the display can operate on 1,000 nits of brightness indefinitely.

Even though the TV Logic reference model can reach a brighter peak brightness of 2,000 nits making it 25 percent brighter than the XDR’s peak brightness level, Apple was able to deliver this performance with more pixels in a more integrated design package. TV Logic cautions people to only use its reference model in a well-ventilated area and add external fans when necessary. Apple’s lattice design supposedly solves this problem. The monitor can reach peak brightness of 1,600 nits when in temperatures less than 25 degrees Celsius, or the equivalent of 77 degrees Fahrenheit.

Apple also edges ahead of competing displays with its proprietary True Tone technology, which automatically adjusts the display depending on the type of ambient light and your overall lighting conditions, making it easy to get accurate colors when you’re moving workspaces.

Beyond XDR: Viewing angles and color calibration

Beyond HDR support, Apple’s Pro Display XDR is able to stay toe-to-toe with the best reference models, delivering support for wide color spaces. Both the XDR and a reference monitor like the TV Logic displays are accurately calibrated, so color rendering on the panels should be comparable. Both displays support the P3 wide color space alongside 10-bit, 1.07 billion true colors. This makes the underlying color reproduction technology very similar.

With Apple’s large panel, it claims you don’t need to sit front and center to experience accurate colors. Apple claims that the super-wide angle of its XDR panel delivers up to 25 times better off-axis contrast compared to a typical LCD panel.

Pro users experienced with working on content on matte displays to reduce glare and reflectivity will also appreciate Apple’s new coating technologies. Most reference monitors like the TV Logic use an anti-glare coating, but according to Apple, that could create a hazy image. To combat that, an anti-glare option was created with a new nano-technology where Apple used lasers to etch the screen with a pattern to reduce glare while maintaining a clear screen. The anti-glare model adds an extra $1,000 to the price of the display. Both the anti-glare and full gloss versions of Apple’s XDR displays are fully laminated in an effort to reduce reflectivity to just 1.65 percent.

What you’re getting with Apple’s XDR

We don’t know if the XDR is such a big leap forward that required a renaming of the standard. Then again, it’s clearly in a different league as what is sold as an “HDR monitor” these days — a different league even than the best HDR monitors available. The Pro Display XDR does real HDR getting a color calibrated panel, a slightly brighter (but still not the brightest) display, increased pixel resolution jumping from 4K or 5K to 6K, and seamless Mac integration with up to 60Hz refresh rates.

And even though a single XDR panel already is more than 40 percent larger than the iMac 5K display, Apple claimed that when combined with a Mac Pro, you can connect up to six of Apple’s Pro Display XDR together using the Thunderbolt 3 connector. This setup delivers 120 million pixels for an even larger creative canvas.

Though the Pro Display XDR’s high price tag will keep it out of the reach to pretty much everyone, Apple has taken many of the important HDR features of significantly more expensive pro-quality reference monitors and made them more accessible to at least some creative professionals. Rather than spending tens of thousands of dollars on a reference monitor to bring calibrated HDR displays into a creative workflow, Apple’s Pro Display HDR brings these coveted features at a more affordable starting price of $5,000. Even if Apple neglected to improve on any of the HDR specifications, this democratization of technology can help drive more HDR content, and that’s a big win for consumers. Who knows — maybe we’ll begin to see more monitors that can actually show true HDR in the future made outside of Cupertino.