If you want to know how someone feels, there are only a few cues to rely on. You can study their facial expressions, consider the content of what they say, and tune in to the tone of their voice. But that can pose a challenge for video journalists and documentary filmmakers covering sensitive subjects, because the easiest ways to anonymize a source is to scrub out things that make them relatable by pixelating their face or distorting their voice. Their story remains the same but the characters themselves can appear crude.

Steve DiPaola, a computer-based cognitive scientist at Simon Fraser University, thinks there’s a better way. He thinks anonymity can be both beautiful and true to the emotional aspects of the people whose identity it’s concealing.

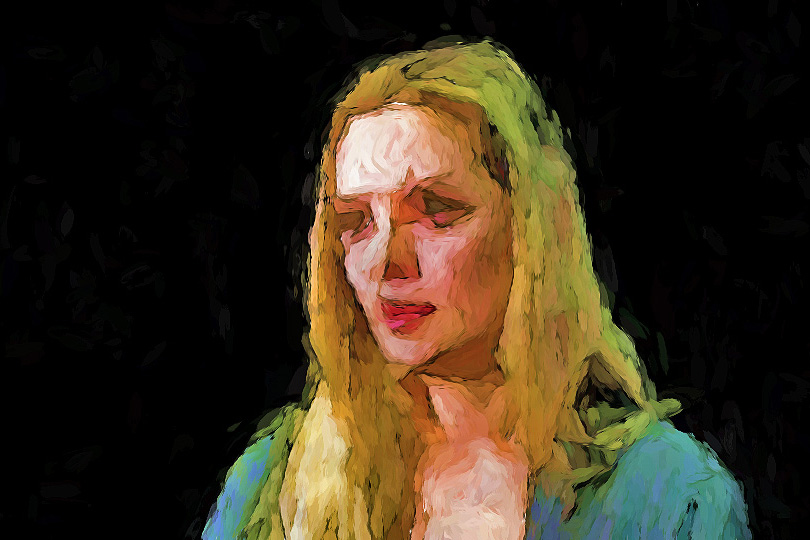

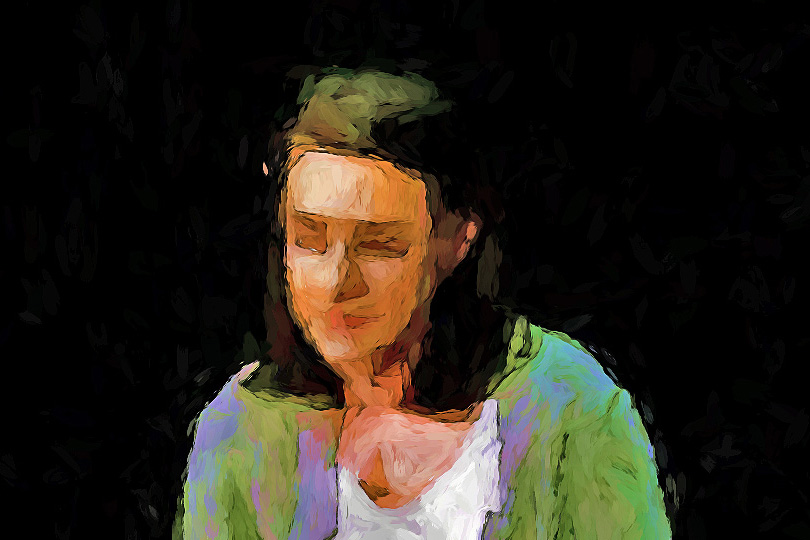

To that end, DiPaola and his colleagues have developed an A.I.-generated anonymity system that “paints” over video frames, using inspiration from masters like Picasso and Van Gogh to reimagine a person’s appearance. The goal is to minimize outer resemblance but maintain fidelity to a subject’s inner character, allowing their facial expressions and vocal inflections to shine through. If deployed by journalists, the system could support more intimate and relatable stories, particularly in virtual reality, where the power of empathy has proven particularly strong.

With the rise of VR in journalism, the need for more nuanced and affective ways to represent anonymous sources is key.

The project began for DiPaola as a way to make an A.I. system that was capable of creating art on it own. A number of algorithms later, he and his team focused their efforts on a fine art painting, and then, more specifically, one that could paint portraits. But after a small grant from Google News and the Knight Foundation, DiPaola — along with Kate Hennessy, a cultural anthropologist at SFU, and Taylor Owen from the University of British Columbia’s journalism school — reworked their system towards providing anonymity for journalists.

The pivot was apt. With the rise of VR in journalism, the need for more nuanced and effective ways to represent anonymous sources is key. Hearing a first-hand account just isn’t the same when the persecuted person’s face is pixelated and their voice is distorted by a few octaves.

For DiPaola, fine art portraiture offered the perfect guide. Master painters don’t just depict their subject from the outside. They capture an inner essence as well. From decades of study and practice, and techniques handed down through generations, great portrait artists can show a subject’s personality through a series seasoned brush strokes and blended colors. DiPaola aimed to teach the A.I. to look past the surface layer and reveal what subjects are feeling inside.

“You tell so much with your eyes, eyebrows, and facial movements,” DiPaola tells Digital Trends. “Even the way you jerk your head and look down — so much of that was just lost in the pixelation technique.”

The resulting system is both beauty and beast, relying on five Linux computers and a five step process to anonymize a video.

“We tell so much with our eyes, eyebrows, and facial movements.”

To start, the system identifies a subject’s facial features, placing dots around the eyes, mouth, and nose like standard facial recognition systems do. Users can then use a tool to manipulate the features, for example, raising the subject’s forehead, widening her eyes, and lowering her ears. Depending on how significant the changes, this subject may already look unidentifiable.

“Before the A.I. painter even starts painting, steps one and two help change the look of the sitter image,” DiPaola says.

In the third step, the A.I. cuts the face into geometric planes. DiPaola calls this the “Picasso or Cubist approach.”

And in steps four and five — the impressionistic and Van Gogh-like phases — the AI adds inky edge lines and brush strokes.

In DiPaola’s vision for the system, a journalist, producer, or even the subject herself could interact with the platform and adjust how refracted the final product is. The system then applies this anonymity to every individual frame in the video.

The researchers haven’t conducted a large-scale study to test how well their system conceals a source, but in pre-study they found subjects were satisfied with the level of anonymity and participants were more engaged when watching videos painted in this style. And the system gained interest from major news outlets like the Washington Post and Frontline, when the researchers presented the work at a conference in July.

“Can you actually have videos of yourself that are more about your inner and less about your outer?”

But anonymizing sources might just be the beginning. DiPaola is interested in becoming something of a digital cupid, working his summer group at SFU’s School of Interactive Arts and Technology to investigate how the system could be adapted for the dating world.

“Dating sites are using videos more often,” he says. “There’s a lot of data that show decisions are made very quickly based on how the person looks, which is too bad at times. Can we actually refine this process so that you’re looking at how somebody is and not just how they look? By anonymizing the footage, attractiveness is not the first thing you think about. Can you actually have videos of yourself that are more about your inner and less about your outer?”

This is, to be sure, a farfetched idea — and one most dating app users would likely approach with caution. But DiPaola’s ambition is compelling, and just a decade ago few would have foreseen the progress that’s been made by A.I. artists. Who’s to say algorithms can’t someday play matchmaker as well?

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Steve DiPaola’s last name.