The window (the UI element, not just the operating system) was a revelation when it first appeared. Before it, programs generally ran full-screen, and most did nothing when they weren’t in use. A computer could do many things – but only one thing at a time. After the invention of the window, the computer became a master of multi-tasking.

Microsoft Windows rose to dominance on the back of this revelatory feature. It was an extinction event for the world of computing. Before it, prehistoric, text-based interfaces plundered along, generally handling one task at a time. Then the window struck, and the shockwave of its arrival marked the difference between early and modern PCs.

Yet the window isn’t perfect. It’s chunky, disconnected, and uses individual, locally processed programs as its fundamental building block. That made sense in the 1980s, but today, in our multi-device, cloud-powered world, it’s restrictive. Smartphones proved the future is elsewhere. The death of Windows was inevitable the moment Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone. Now, we finally have a glimpse at what will replace it.

An active lifestyle

Microsoft isn’t blind to this issue. On the contrary, it’s hyper-aware of the problem, and is already working on a solution.

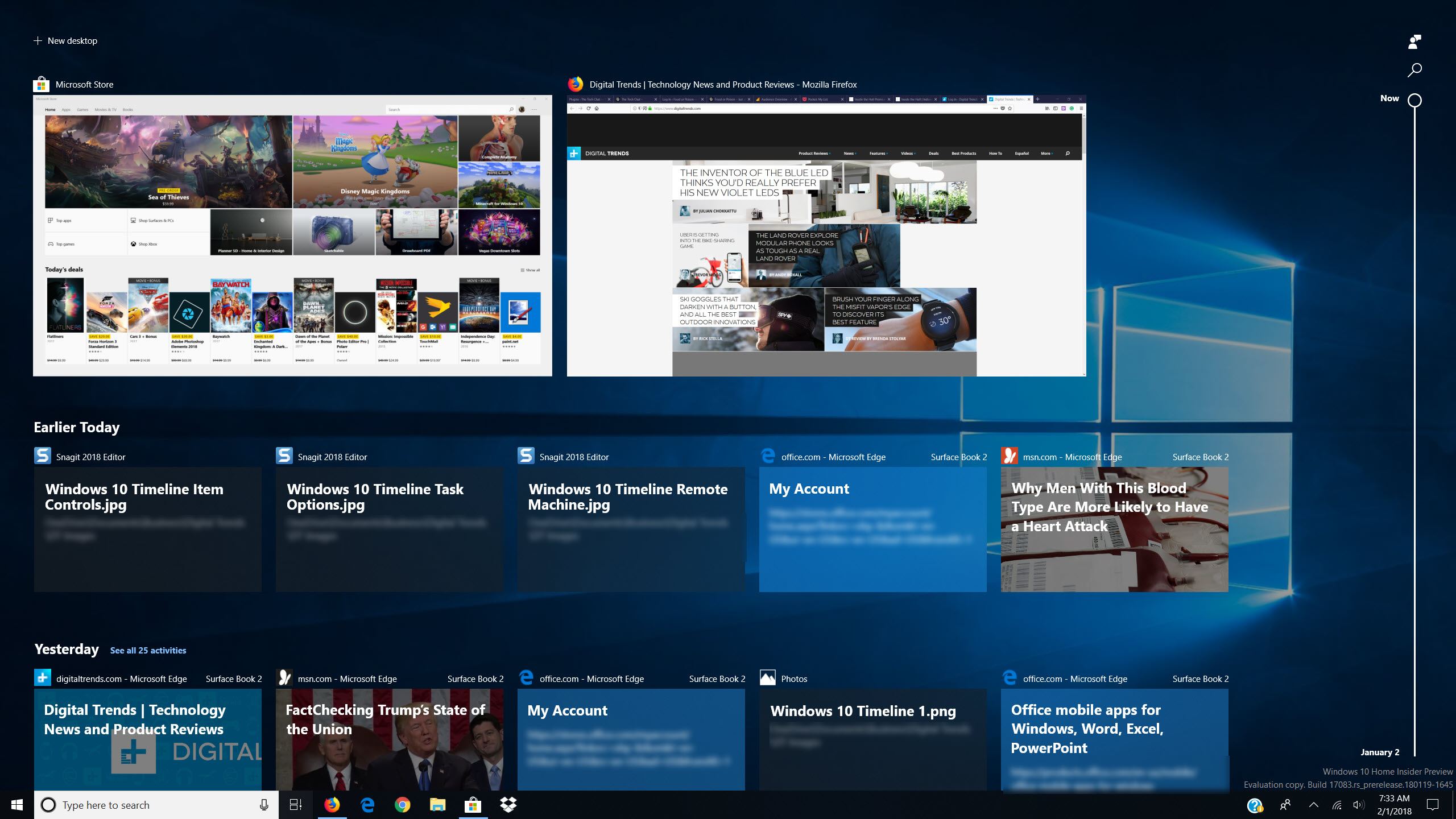

Timeline, which just rolled out to everyone in the latest Windows 10 update, is the beginning. It makes a subtle, but significant, re-work of how Windows groups open and closed software. Instead of focusing on just open, active programs on the local Windows machine, Timeline deals with when and where apps were opened. It then places them appropriately, even across multiple devices — “activities,” as Microsoft calls these groupings.

This is a more flexible, human-focused method of multi-tasking, one that’s designed to directly address how people think about work as they manage it in the real world. “Every time I come back to my PC, trying to recall what I did at 2 o’clock yesterday is way to painful to get me back into my flow of my task,” Shiipa Ranganathan, General Manager at Windows Mobility, told Digital Trends. “It would still be a window that I’d open up, but it’s really blending web, my apps, creating a native construction in my operating system that allows me to recall things pretty quickly.”

That’s just the beginning. Microsoft also talked about Sets, the next step of this evolution, at Build 2018. Sets draw in metadata to intelligently group programs not just by time, but also focus. Let’s say you’re working to edit some photos but end up distracted by cat videos halfway through. No problem! Sets should be able to recognize the programs and windows you’d used for that activity, so you can later open them all at once. Microsoft will even suggest a Set to you if it believes you intend to resume it, or surface Sets in Cortana when it appears you’re searching for the activity.

Timeline and Sets sound useful on their face. Yet the real potential lies beneath the surface. Both these features tap into Microsoft Graph, the company’s cross-service data platform. There’s a good chance you’ve never heard of this, and there’s a good chance you’ll never need to. The Graph is built to seamlessly connect Microsoft software like Windows, Office, and programs powered by Azure. It’s working best when you don’t notice it exists at all. “What we’re doing is using [the Graph] about the identity, and the devices this person has, to establish discovery and help command these two devices,” Shiipa explained.

Forget ‘Windows as a service.’ That’s so 2015. What matters is Microsoft as a service.

The transformation that began when Windows 10 was released is coming to completion. Forget “Windows as a service.” That’s so 2015. What matters is Microsoft as a service. At Build 2018, Microsoft told developers to think of themselves not as Windows developers, or Office developers, or Azure developers, but as ‘Microsoft 365’ developers.

That’s not to say Windows is going away, of course. Shiipa sees the path forward not one of replacement — but growth. “We’ve always been building it like this,” she said. “Windows is a platform that allowed a bunch of people to stay production, be creative, use the web. To me, this is really an elevation of being able to have all these products work seamlessly together.”

A space-time Windows Phone paradox

Microsoft 365 is an ambitious attempt to bring all the company’s offerings into a cohesive whole. It’s also more than that. By expanding beyond the window to activities, the company is making yet another attempt to edge into mobile devices.

That’s possible because an activity exists at a higher level than a window. The former is an organization of data, while the latter is a specific user interface element. An activity, unlike a window, can exist in many forms on many different devices. There’s no reason its data can’t appear on a tablet, or smartphone, or even an IoT device. Activities, when powered by Microsoft’s Graph, can also suck in all sorts of useful metadata, making them easier to find, group, and understand on any device.

The Your Phone and Microsoft Launcher for Enterprise apps shown at Build 2018 are a hint at where Microsoft hopes to go with this. Windows Phone is dead, but the company’s mobile ambitions aren’t, and the cloud is its new weapon. It’s a familiar strategy, really. Microsoft gained on a stranglehold on the PC market by building an operating system everyone wanted to use. What if it could do the same to smartphones, using its own cloud-powered services?

“Let’s say you open Powerpoint [on your iPhone],” Shiipa explained. “You have access to you most recently used Powerpoint apps. That’s actually pulling from the Graph, because it knows you’ve been doing those activities on your PC.” Your Phone works the same way, using Graph to readily surface information you’re already interested in and present it in a new way that helps close the gap between devices.

This strategy does seem like a long shot, but it’s plausible. More importantly to you and me, it adds unique and useful new capability. Apple and Google have a lot of cool products and, in their own ways, have ambitious cloud services. Yet neither does much to help you organize how you use software on even one device, never mind all of them — and neither has the deep roots in productivity software that Microsoft has.

It’s hard to imagine closing a research project involving multiple websites and apps on an iOS tablet and then opening it up on a Mac, weeks later, with just one click. The same is true in Google’s services. Microsoft is the only company in a position to make it possible. That might – just maybe – give it an edge.