(in)Secure is a weekly column that dives into the rapidly escalating topic of cybersecurity.

With privacy-centric European Union legislation set to take effect soon, and on the heels of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Facebook recently introduced a new data policy. Just when you had the old one memorized, right? Facebook says it wants to be more transparent about how its Products track almost everyone who uses the internet – even those without a Facebook or Instagram account.

We’ve gone through the policy to help you make sense of what Facebook is trying to communicate.

What kinds of information does Facebook collect?

Facebook is collecting and using your posts, messages, photos, and other information you provide, such as the groups you belong to, the pages you visit, hashtags you use, and so on. Even if you don’t identify your religion, the site may still infer something about your identity or interests if, say, you join a Bible study group. Purchasing items through the site, spending three hours a day browsing photos on Instagram, and being active in a group, will all feed into the picture Facebook has of you.

Facebook isn’t just Facebook. It’s also Instagram, WhatsApp, Oculus, and so on.

Facebook sucks up data on the devices you use, too — probably more than you expect. Not only does it know what kind of phone or PC you have, your operating system, and browser type, it’s analyzing how much battery you have left, and your storage space. It’s also looking at your mouse movements to see what you hover over or blaze past. If you have Facebook open in the background but aren’t using it, it’s clocking that, too.

The Facebook portfolio

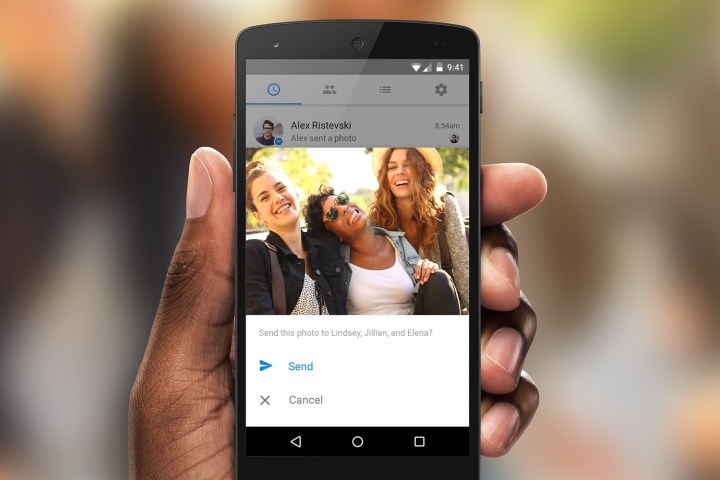

Facebook isn’t just Facebook. It’s also Instagram, WhatsApp, Oculus, and so on. The way you use these sites affects not only you but your “Friends” as well. When you comment on your sister’s post, that interaction affects the profile Facebook has of both of you. If you sync your contact data with the Messenger app, the company gets the phone numbers and email address digital black book — even if they don’t use Facebook.

- 1. Facebook also owns Instagram, Oculus (maker of Oculus Rift and Oculus Go), and WhatsApp.

Maybe your Facebook privacy settings are on lock down, but you’re looser on Instagram. Well, those interconnected sites are sharing amongst themselves. For example, Facebook analyzes your communications in Messenger, though it claims only for your safety (like to prevent malware). Recently, a user was upset to realize the Messenger app was logging his call history.

It knows where you are

When you gave Facebook access to your camera or photos or GPS, you were probably thinking about how it would make things convenient for you. But it’s not just that one photo it has access to — it has everything in your library.

Game apps, retailers, and all kinds of sites and companies are sharing information about you with Facebook.

The more devices you use to log on to Facebook, the more information it’s going to gather. Ditto for the company’s apps. You might want to consider limiting your Facebook use to a single device. If location privacy is important to you, you could stick to a laptop, but keep in mind that Facebook also knows your IP address and can scrape metadata from photos to get location information. Your “Friend” might tag you when she checks in at the park for your Saturday softball practice.

What about non-Facebook users?

Facebook has denied it creates “shadow profiles” of non-users, but even if you don’t have a Facebook page, you’re not anonymous to the tech giant. Game apps, retailers, and all kinds of sites and companies are sharing information with it. When you click any kind of user agreement, you’re giving away more than you bargained for.

How does Facebook use this information?

Now that Facebook knows you were born in Iowa (as was your sister, Mary), eat at Chili’s, and listen to a lot of Cardi B (because you log into Spotify with your FB account), it can personalize your experience, the company says. It might tailor your News Feed to show something Mary hearted or commented on, because she’s your sister, and you two “Like” a lot of the same things. Maybe you’ll see a cooking site’s recipe for copycat Chili’s queso. And Ticketmaster might advertise Cardi B’s tour for you, since you have location services turned on, and she didn’t cancel her Dallas performance.

It’s about more than ads

Feeling targeted by Facebook ads is often the first people think of when the topic turns to how the site is using your data. But your whole experience is curated to what the site’s analytics think you want. And remember that it’s gathering this not just from ads you click on, but groups you’re a part of, apps you use, and sites you visit — even when you’re not logged in.

Facebook has been accused of not just including groups, but also excluding them. A makeup company might choose to exclude men over the age of 65, for example. This crosses the line into discrimination if rental companies and landlords are putting “stay-at-home moms” and “corporate moms” on the list they don’t want to advertise to, according to a lawsuit that the National Fair Housing Alliance recently filed. The company is facing another lawsuit in Illinois, which claims Facebook violated the state’s Biometric Information Privacy Act by utilizing users’ photos for its facial recognition technology without their permission.

But the ads are eerily accurate

Any site that has a Facebook “Like” button can send data, including your IP address, back to the social media company, even if you don’t click on it. Websites use Facebook’s advertising pixel to have the site target you with ads if you add flip-flops to a shopping cart — but don’t buy them — or search for “New Orleans” on a hotel-booking site. Retailers and other sites can create “Custom Audiences” from this information, then have Facebook target everyone who visited a specific URL, or watched one of their videos.

You have control over whether your posts are public or more private, but you can’t control your “Friends.”

Facebook is getting rid of its “Categories” advertising feature over the next six months, but that doesn’t mean it’s collecting less data. Data brokers like Acxiom and Experian know a lot about you, too. (You might remember the man who received a letter from OfficeMax addressed to “Daughter killed in a car crash”; the company blamed a data broker.) They gain details thanks to public records and databases like property records, loyalty card programs, surveys, voter rolls, dealership sales, and more, according to The Washington Post.

Using the profile of a person who recently bought a Camry, for example, they can use Facebook’s categories to find others who might also want to buy that car. Data brokers will continue to mine your information, and advertisers can still create targeted ad campaigns, but they have to do so using “data that they have the rights, permissions, and lawful basis to use,” Carolyn Everson, Facebook’s vice president of global marketing solutions, told The Wall Street Journal.

How does Facebook share your information?

Call this the “What about your ‘Friends’” section. They’re having an impact on what Facebook knows about you, and they control some of the data Facebook says you own.

Your friends are spilling info on you

You have control over whether your posts are public or more private, but you can’t control your “Friends.” That video of you re-enacting Christian Bale’s iconic dance from Newsies is likely endearing, but not something you want made “public.” If they posted it, though, you can’t change its status, and may not have much recourse for getting it removed if it doesn’t violate the community standards. Facebook is rolling out a new appeals process, but that seems to be aimed at users who have had their content taken down unfairly.

Also, if you comment on someone’s post when it’s just among “Friends,” they can go back and make it public later. That’s important, because if you have a falling out and they block you, you can’t delete your comments or posts from their page.

What do you own?

During his testimony before Congress and the Senate, Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, repeatedly said users own their information and content. But it’s using the heck out of it while it’s hosting it to give advertisers more insight into your buying preferences. The female marines who had their nude photos shared on a Facebook page without their permission probably didn’t feel like they owned that content.

The timeline and tagging settings let you prevent people from adding posts to your timeline or tagging you in their posts, but they can still upload whatever they want to their own page. Facebook’s opinion is that you should “be careful who you share stuff with.”

Another oft-repeated phrase in Zuckerberg’s testimony was that the company doesn’t sell your data to advertisers. Instead, it puts you in those buckets — mid-20s females from California who knit — and tells advertisers the types of people seeing the ads. If you give permission, though, Facebook will pass along identifying information to companies.

Facebook also points out that if the company gets a new owner, your data is part of the sale

What about apps?

Scientists and software engineers are using the treasure trove that is Facebook to investigate all kinds of things.

The Cambridge Analytica fiasco happened because Facebook used to be lax with app data. It’s since tightened up the information apps can gather about your friends, and it’s in the process of adding more restrictions. When apps or websites are integrated with Facebook, they’re getting more information out of what you’re doing. If you link a website’s app to your Facebook account and post one of its links to your page, the website will know.

The research report

Facebook shares data with research institutions, including its own. Scientists and software engineers are using the treasure trove that is Facebook to investigate all kinds of things. It’s not just feel-good experiments like finding ways of computer-generating photo descriptions for the visually impaired. Researchers are diving into the minutiae of how users act on the site, like if receiving a gift causes you to give one in return, whether you click on spam, and what prompts you to untag a photo.

Every project undergoes an ethics review by a research lead, according to Facebook blog post. (The research manager who wrote it points readers to another post from October, 2014, when the company “first outlined” its approach to research and review. That was a few months after users learned about what many claimed was an unethical mood-manipulation experiment.)

While the data is mostly anonymous and aggregated, some, like those involving opt-in questionnaires, isn’t.

Hitting delete

Deleting Facebook isn’t like unsubscribing from an email list. You don’t just click a button and watch your digital footprint vanish in a puff of smoke and memories. It takes the company 14 days to finally, permanently erase this part of your digital life. Before you take that step, you’ll probably want to download your information (you own it, after all), set up some sort of text group or email thread with people you actually want to hang out with, and so on.

Facebook will hand over your account information if requested via search warrant, court order, or subpoena if they “have a good faith belief that the law requires [them] to do so.”

Deactivation is less drastic, but it doesn’t have the same effect as deletion. Everything from your photos to your “Likes” is kept, and you can even still use Messenger, but your non-“Friends” shouldn’t be able to find your profile. You might still show up – with just a generic silhouette instead of your profile photo – in “Friends’” lists. Facebook will still track you per usual, as well.

Facebook directs you to your settings page to find information about deleting your account. It’s not there (though deactivation is). You can start the deletion process from here.

How does Facebook work with governments and law enforcement?

Facebook will hand over your account information if requested via search warrant, court order, or subpoena if they “have a good faith belief that the law requires us to do so.” That includes the laws of countries outside the U.S. This applies in suspected cases of fraud, illegal activity, and terms of service violations, and if there’s reason to believe such action would prevent someone’s injury or death.

Government requests

Governments request account information at vastly different rates, which partly has to do with the number of users per country. In some countries, social media posts criticizing the government can lead to arrest. The recently passed Cloud Act has raised some concerns that foreign governments might obtain data on their own citizens from U.S. platforms during an investigation. Police often monitor social media. The American Civil Liberties Union raised concerns over some tools departments were using to track protestors. Facebook has also agreed to censor content in several countries.

Between January and June 2017, Facebook gave some user data in most of the cases that occurred in the following countries:

| Country | Total requests | Percent granted | Estimated number of users |

| India | 9,853 | 54% | 241 million |

| United States | 32,716 | 85% | 240 million |

| Brazil | 2,056 | 57% | 139 million |

| United Kingdom | 6,845 | 90% | 44 million |

| Japan | 6 | 33% | 25 million |

| Australia | 704 | 77% | 15 million |

| Sweden | 317 | 88% | 5 million |

The number of users is estimated, as Facebook’s own metrics aren’t always accurate.

People often think because they have nothing to hide, data gathering is fine. But just because you’re not laundering money in your living room, doesn’t mean you’d want strangers watching your every move through a security camera. If tools become more sophisticated at catching criminals, shouldn’t they also evolve to be less invasive?

How does Facebook transfer data globally?

Facebook is a global company that transmits and stores its (your) data around the world. Before the digital privacy laws of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation go into effect May 25, Facebook is moving 1.5 billion users’ information from its Ireland headquarters to California. Accounts in countries such as Australia, Thailand, and Brazil won’t benefit from the increased security of the E.U. legislation. Facebook will adhere to this law “in spirit” across the board, Zuckerberg told Reuters.

The U.S. is playing catch up when it comes to these protections. On April 24, Senators John Kennedy (R-Louisiana) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minnesota) introduced the Social Media Privacy and Consumers Rights Act of 2018. It includes provisions such as requiring sites to show users information that’s collected about them and allowing social media users to opt out of data tracking. If such a law passed, it wouldn’t prevent Facebook from moving other countries’ users elsewhere.

You’re tired of Facebook tracking you. What can you do?

Live in a van down by the river? Make sure you pay cash for the van and find an ad for it in a physical copy of your local newspaper. Just kidding. Here’s a guide to changing your Facebook privacy settings.