Yesterday Facebook announced the international rollout of its face recognition feature for tagging photos. The tool was implemented for North American users way back in December, at which point people went through the obligatory Facebook-privacy scare phase. Compared to some of the site’s other updates, however, the fallout was mild. But now that Facebook face recognition has made its way overseas, it’s time for a renewed round of outrage.

Yesterday Facebook announced the international rollout of its face recognition feature for tagging photos. The tool was implemented for North American users way back in December, at which point people went through the obligatory Facebook-privacy scare phase. Compared to some of the site’s other updates, however, the fallout was mild. But now that Facebook face recognition has made its way overseas, it’s time for a renewed round of outrage.

Why people are worried

Face recognition was rolled out to a group of Facebook users stateside earlier this year, but the increased attention has caused new user worries and insights from security experts. As with every new Facebook update, some of the concern can be blamed on hype and over-zealous speculation.

Just last week at the D9 Conference, former Google CEO Eric Schmidt talked about the consequences of how quickly this technology is moving. “We actually built that technology and we withheld it. As far as I know it’s the only technology Google built and after looking at it we decided to stop.” He also commented that it has the potential to be used in “very bad way[s] as well as [in] a very good way.”

It’s also sparked renewed Facebook privacy concern because of the recent attention the site has been receiving. Some government authorities believe all Facebook settings and applications should be opt-in, meaning they are turned off until users say otherwise. Now, it functions the other way around. This high-profile new feature will become something of a soap box for privacy proponents to stand on.

The good

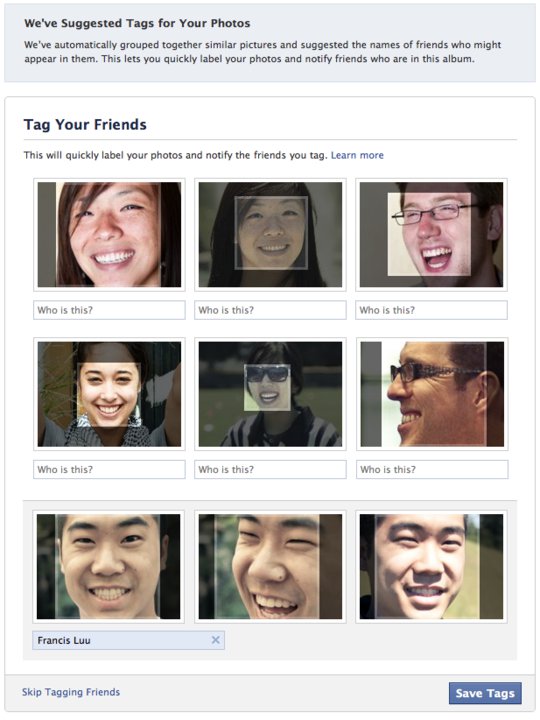

Facebook is the most popular platform for photo sharing, and was recently granted a patent for its tagging system. The method in which you are notified of newly tagged images of yourself and how you respond to them is specifically what Facebook originated, and it’s a system that has changed the way we interact with and use photos online. There are useful qualities to tagging: It’s an easy way to share photos with the people in them, and adds an organizational element. In some cases, being able to match a name and face have proved useful (we know, this also lends itself to some stalker tendencies, but we’re still on the good for now). In a blog post about the new feature, Facebook explained that while users love

The bad

The social network already has a strong grip over millions of people’s personal information, and this seems like a final step toward knowing everything there is to know about us – what we look like. The feature means that the more we tag people the more Facebook’s technology learns about our appearance, and even if you opt-out the system will still recognize you. It might not be broadcast to your friends, but the data about your image will still be in Facebook’s hands and it will have a searchable collection of all its users’ photos.

What’s also unfortunate is you have no idea if this software has been used for your image. Unless you keep up on Facebook news (which it’s actually quite hard not to) or religiously read the site’s blog, you may have missed this boat altogether. If you see that you’ve been tagged in a photo, there’s nothing that alerts you saying “this photo was tagged using face

Enabling tagging in general comes with some obvious strings attached: It gives the world access to anything anyone (depending on your privacy settings) tags of you. And if you have any less than discreet contacts or activities, this can be dangerous. But at the very least, you are (in nearly every situation) being identified by people you know who took a photo of you. This update means you’re being identified by Facebook, which can be a scary thing.

EU privacy probe

The EU has not looked kindly on Facebook’s privacy, or lack thereof. BusinessWeek reports that Gerard Lommel, a member of the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party says “Tags of people on pictures should only happen based on people’s prior consent and it can’t be activated by default…[this] can bear a lot of risks for users.” Authorities want to “clarify to Facebook that this can’t happen like this.” The new recognition software isn’t the only problem: Investigators want to challenge Facebook’s tagging system altogether. Would it be nice to approve photos tagged of you before they hit your profile? Yes. Is that going to happen? Probably not. Facebook hasn’t required your preapproval to tagged photos from day one, and that was awhile ago. Sure, it didn’t have 500 million people’s pictures in 2005, but it would be challenging to reverse this policy.

Questions

There are a few things that are still unclear. For instance, if someone uses the new software to tag a photo of you that you then untag, does Facebook un-recognize your likeness? Or is that information still stored, and it realizes you simply untagged the photo for preference’s sake and not because it wasn’t you?

And what’s the end game here? This question seems to be what’s most upsetting privacy proponents. If Facebook is able to create a searchable database of its users’ images, wouldn’t that mean it’s possible to search for someone with nothing more than a photo? That means a stranger could take your picture, upload it to Facebook, and find you. Of course, enabling user image search could be the furthest thing from Facebook’s mind – but the fact that it would be possible is a little chilling.

Just to take this to conspiracy theory levels, were the feature to become said database and a widely accepted technology on Facebook, misidentification could pose a problem. All sorts of issues could arise by having your likeness swapped with someone else’s.