Around a year ago, I claimed that gaming laptops were lying to us. It was hard not to when you couldn’t trust the spec sheet to give you an idea about how a laptop would perform. I hoped my annual check-in would bring some improvements, but unfortunately, the situation with gaming laptops has only gotten more complicated.

Problems with graphics card power are still present, but now processors are dissuading buyers as well. The spec sheet should tell you a lot about how a gaming laptop performs, but the situation in 2023 is a lot more convoluted than that.

Graphics power is still a problem

First, we have to check in on GPUs. Last time around, I focused on the Total Graphics Power (TGP) spec in mobile graphics cards. In short, mobile GPUs have a range of power that they’re allowed to operate at, which leads to some strange situations where a weaker GPU on paper could outperform a more powerful one.

My main gripe, at the time, was that very few laptop brands actually listed the TGP alongside the graphics card, so the only way to find out how a machine performed was to read an individual laptop review. That situation has improved, but there are still problems with TGP.

Brands that went on to list TGP as a spec in the last generation have backpedaled with a new generation of graphics cards now. That’s not a big problem for a laptop like the Razer Blade 18, assuming Razer lists the spec once the laptop goes on sale. It’s problematic for a machine like the Lenovo Legion Pro 7i, though, which is currently available for sale on Lenovo’s website without a listed TGP.

Similarly, Alienware has yet to update its power range for new RTX 40-series graphics cards. As we saw in the previous generation, there’s a good chance that brands will eventually list TGP, but there’s no reason to delay that spec. As laptops like the Asus ROG Strix Scar 17 show, brands should start listing the TGP spec as soon as the laptop is available for sale.

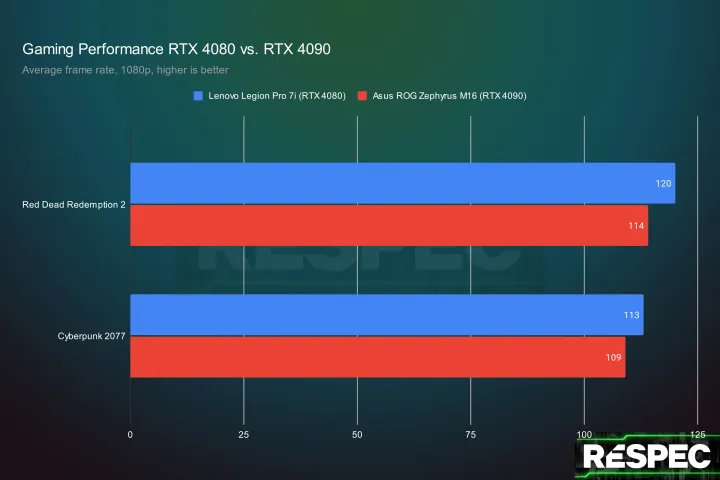

TGP is so important because it still represents massive performance gaps in gaming laptops. We’re already seeing the mobile RTX 4080 outperform a mobile RTX 4090 in some cases, and that’s among high-end gaming laptops.

For example, the RTX 4080 inside the Lenovo Legion Pro 7i is faster than the RTX 4090 inside the Asus ROG Zephyrus M16 in 3DMark Time Spy, Red Dead Redemption 2 and Cyberpunk 2077. And the Lenovo laptop is around $500 cheaper.

I can tell you that the Zephyrus M16 tops out at 145 watts of max TGP — 15W less than what’s possible with the card — but not the TGP of the RTX 4080 inside the Legion Pro 7i because Lenovo doesn’t list it. We’re already seeing performance gaps between two high-end, 16-inch laptops. Once a wider crop of creator-focused laptops hit the market, the gaps will be even wider.

Nvidia is well aware of this issue, thankfully. The company tells me that if you normalize the wattage between two different GPUs, such as the RTX 4080 and RTX 4090, they’ll always fall in the way you’d expect; at the same wattage, the RTX 4090 will always outperform the RTX 4080. That clinical take may be true, but the reality for gaming laptops is that you’re looking for the best performance possible, and if a machine with RTX 4080 outperforms one with an RTX 4090, there’s still a problem.

I’m not advocating that TGP ranges go away. That would vastly limit the design space available to laptop brands. However, clearer branding would go a long way to inform shoppers. Narrow TGP ranges would help, as well. At the moment, even a few watts in either direction can have an impact on performance, making it hard to trust the name of the graphics card in your laptop.

Processor names are confusing

Even with recent laptop GPUs experiencing growing pains, it’s clear that brands are aware of how important TGP is. I’m hopeful, at least, that clearer TGP listings will start flowing out over the next couple of months. Unfortunately, AMD has introduced a new problem for laptop shoppers to contend with: CPU naming.

Informed shoppers know to look at the first number in a CPU name to figure out which generation it’s from. A “13” in front of an Intel processor means that it’s a 13th-gen CPU, while a Ryzen 7000 CPU is from AMD’s most recent generation. That’s the assumption, but AMD isn’t delivering on it.

Ryzen 7000 mobile CPUs don’t all use AMD’s most recent Zen 4 architecture. Instead of the long-standing tradition of the first number in a processor name noting the generation, for AMD, it now notes the model year. The third number, instead, notes the architecture it uses. Confused? I don’t blame you.

The chart above shows how the new naming scheme breaks down practically. This convention can lead to some very unfortunate situations. For example, you can theoretically have a Ryzen 7 7710U, which would carry AMD’s original Zen architecture despite being branded as a Ryzen 7000 processor. Keep in mind that AMD debuted the original Zen architecture in 2017.

I don’t think anything malicious is going on here, to be clear. It’s very unlikely that we’ll see a high-end laptop sporting an architecture that’s half a decade old, and AMD is making some attempt to separate the older architectures with a different colored badge. There’s an argument that AMD was attempting to simplify its branding by having older architectures in budget-focused machines fall under the same category as its flagship chips.

Even if that was the intention, the result is far different. CPU naming conventions are notoriously complex, but there has been a lot of work by AMD and Intel to simplify the process for an average buyer. Up until AMD’s shift, you could at the very least look at the generation and the Ryzen 7 or Core i7 branding and get a general sense of where the processor fell in the lineup. It wasn’t a perfect system, but it worked.

AMD’s new naming convention makes that process far more complicated. Not only do buyers need to know about the model year and lineup segment, but they also need to know about architectures and which number showcases the architecture the processor is using. And that’s before we get into wattage ranges with mobile processors, which are confusing on their own.

A clear path forward

Between year-old architectures in processors and broken naming on mobile graphics cards, it’s tough to buy a gaming laptop in 2023. It’s easy to write off the naming conventions of major brands, especially among well-informed buyers who know the ins and outs of the latest tech. But even among buyers who have a solid grasp of generations and product lineups, there’s a lot of room for error.

There’s a clear path forward here. For GPUs, we need more branding to determine which are more powerful and which are less powerful. TGP numbers help and should be listed as a critical spec. But even some branding on Nvidia’s end to note graphics cards running at maximum wattage or base wattage would go a long way in separating the wheat from the chaff.

For CPUs, it’s a matter of staying consistent. There’s room for convention changes like AMD is rolling with, but it seems tone-deaf and intentionally misleading given the established naming conventions laptop buyers have used for decades. Maybe instead of segmenting older architectures under new names, AMD could just sell those processors as the older generations they are. They’d probably sell a lot fewer laptops, but that would be a better representation of the power actually on tap.

Ultimately, though, the best way to avoid these pitfalls is to read individual laptop reviews. I’m always an advocate for clearer spec sheets so shoppers are informed about what they’re buying, but it doesn’t look like the situation with gaming laptops is changing any time soon.

This article is part of ReSpec – an ongoing biweekly column that includes discussions, advice, and in-depth reporting on the tech behind PC gaming.