Gaming monitors are lying to us, and they have been for many years. Informed buyers know the tricks that brands play to sell the best gaming monitors, and they’ve learned to navigate the deceptive marketing. But these ploys persist, and 2023 is the year when monitors need to get a little more transparent.

Some of the key areas where gaming monitors mislead buyers have been running rampant for years, while others are fairly new. As we start a new year and look onto next-gen displays, consider this buying advice for picking up your next gaming display, as well as a call to arms to demand manufacturers do better.

HDR

Perhaps the biggest area of misinformation around gaming monitors is HDR, as well as all the specs that relate to good HDR performance. For HDR, the problem boils down to a disparate list of standards that are haphazardly slapped on product listings without concern for what they mean.

The standard for HDR right now is VESA’s DisplayHDR certification. It’s a wildly popular standard, being adopted by more than 1,000 displays over the last five years, and it covers several critical elements for solid HDR performance. Those include peak brightness, local dimming capabilities, color depth, and color gamut. In addition, it specifies specific use cases for these metrics.

VESA explained to me that in tiers like DisplayHDR 1,000, it measures not only peak brightness in part of the screen, but also full-screen peak brightness. A representative said this is important for games where you may see a flashbang effect or something similar, requiring a quick blast of brightness.

However, multiple brands have piggybacked off of VESA’s standard with misleading HDR certifications. The most egregious case came in 2021 when Chinese retailer Taobao listed a Samsung and Acer monitor with a fake DisplayHDR 2,000 badge. There is no DisplayHDR 2,000 tier.

What’s the point of having a standard if nothing is standard?

There are more common and pressing examples, however, and Samsung is a key offender. Although some Samsung displays are certified with DisplayHDR, most use “HDR 1,000” or “HDR 2,000” branding to note HDR performance, with the number usually referring to the peak brightness of the display. Even then, some monitors mislead on the brightness front. For example, the Samsung Odyssey Neo G8 comes with “Quantum HDR 2,000,” despite the fact that it only supports 1,000 nits of peak brightness according to Samsung’s own product listing.

Similarly, Asus’ recently introduced Nebula HDR standard for laptop displays lists vague specs. The standard goes “up to 1,100 nits of peak brightness” and “can have hundreds, if not thousands, of separate dimming zones in a single panel,” but all panels use the same Nebula HDR branding. For example, the 2023 Zephyrus G14 has 504 local dimming zones and 600 nits of peak brightness, while the 2023 Zephyrus M16 sports 1,024 dimming zones and 1,100 nits of peak brightness. Both carry the same ROG Nebula HDR branding. What’s the point of having a standard if nothing is standard?

I don’t have any issues with companies developing standards for their products, but when they’re designed to look like an established industry certification, they’re designed to mislead. At the very least, if companies are going to create their own HDR standards, they should also go through the process of certifying them with a third party like VESA.

This is all the more important considering the specifications HDR touches. Peak brightness, for example, doesn’t account for how much of the screen can get that bright and for how long. Is it one pixel for a fraction of a second, or 10% of the screen for 30 minutes? No one is checking, and you don’t want to be the brand selling a monitor with lower specs on paper.

Contrast ratio has the same problem. Both the Samsung Odyssey Neo G9 (2022) and Alienware 34 QD-OLED list a contrast ratio of 1,000,000:1. However, the OLED panel and its self-emitting pixels on the Alienware 34 QD-OLED means it has a near-infinite contrast ratio, while third-party reviews show the Samsung monitor with around a 15,000:1 ratio. I don’t blame Samsung here, either. It wants to paint its products in the best light, but when these critical specs say so little, it’s hard to believe them at all.

Response time

Response time has long been an area of confusion and misleading specs for gaming monitors. There are multiple ways to test response time, and they produce wildly different results. And, of course, companies that want to sell you gaming monitors are going to use the number that makes their product look its best.

You won’t find a gaming monitor that advertises a response time over 1 millisecond, which makes response time a pointless spec. The vast majority of monitors only list gray-to-gray (GtG) response time, which is how fast the pixel transitions from one shade of gray to another. It doesn’t tell which shades, how bright the monitor is, how long it’s been running, etc., and these all impact the actual response time of the display.

The more telling spec is Moving Picture Response Time (MPRT), which measures the visibility of pixels. This number draws closer to the motion blur you actually see on screen, and motion clarity is the vital component that response time is attempting to track.

Response time is one of the most important metrics for gaming, and product listings do little to clarify how products stack up.

Ideally, manufacturers should list both. You may have a monitor with a 1ms GtG response time, but with a 60Hz refresh rate, the MPRT is 16.6ms. You’ll see blur on the vast majority of objects.

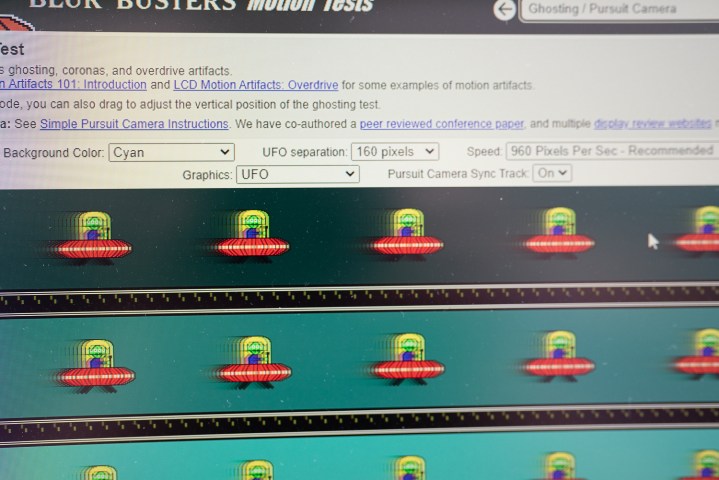

On top of that, monitor brands typically measure GtG response time at high overdrive levels. Pixel overdrive reduces the response time of the monitor and should, theoretically, produce images with more motion clarity. However, overdrive often produces ghosting and coronas, both of which are artifacts that look like motion blur in a moving image. Again, monitor brands usually don’t specify the overdrive level in response time metrics, adding even more confusion to this spec.

VESA is attempting to pull the curtain back on response times with ClearMR. This provides a Clear Motion Ratio (CMR), which is a measure of clear to blurry pixels in a set of tests. This is even more comprehensive than GtG and MPRT specs listed together. It looks at the final image, not just a test pattern, and it accounts for sharpening, overdrive, and the motion clarity techniques that gaming monitors use.

ClearMR just launched last year, and only 33 displays are certified right now. Response time is easily one of the most important metrics for gaming, and for years, product listings have done very little to clarify how products stack up. Listing GtG and MPRT is a good first step, but standards like ClearMR encompass even more.

Resolution

Gaming monitors don’t lie about their resolution, so I don’t want to mislead anyone here. If you see a monitor advertising 4K, it has a 4K resolution. At the very least, I’ve never encountered a monitor that straight-up lies about its resolution.

The main point here is that we could see some misleading branding with future gaming monitors. Samsung’s Odyssey Neo G9 (2023), for example, was revealed by AMD last November as the “first 8K ultrawide.” And coming off the first hands-on time with the press, you can find half a dozen articles claiming it’s an 8K monitor, too.

It’s not an 8K monitor, though. The Rec.2020 standard defines 8K as a pixel count of 7,680 x 4,320. In addition, there are groups like the 8K Association that oversee 8K displays, as well as the ecosystem to power them with content. The new Odyssey Neo G9 has a resolution of 7,680 x 2,160. You’d need to stack two of them on top of each other for a true 8K resolution.

Samsung never claimed its monitor was 8K, but this an area rife for misleading branding going into next-gen displays. As we continue to see exotic aspect ratios and higher resolutions, I have no doubt that “8K” will be thrown around loosely. We’re seeing that already, and that’s with a single monitor from one of the world’s largest brands.

What gaming monitors can do

Gaming monitor brands need to do better, but that’s easy to say. In reality, brands in the business of selling gaming monitors want their monitors to look good on the spec sheet. Are you going to list a 15,000:1 contrast ratio when you can measure 1,000,000:1 under certain circumstances? No one wants to be in that position.

That’s why third-party industry standards are important. DisplayHDR has already set a clear baseline for HDR over the past several years, and ClearMR could clear up — if you’ll forgive the pun — response times in a similar way. Short of an industry watchdog group, these certifications are the only way to set clear standards for quality in gaming monitors, and those have been sorely missing for the last several years.

Although I don’t have a clear path forward, the situation now isn’t working. Spec sheets say very little about how a gaming monitor actually works, and in a space rife with misleading branding, critical elements like HDR performance, brightness, and response time need defined standards that consumers can rely on. Otherwise, you might as well ignore the spec sheet completely when buying a gaming monitor, and I certainly don’t want to make my buying decisions that way.

This article is part of ReSpec – an ongoing biweekly column that includes discussions, advice, and in-depth reporting on the tech behind PC gaming.