Physically, I visited the Portland office of software developer Object Theory, surrounded by programmers and designers tapping away on the usual startup blend of MacBooks and PCs. But what I saw was the 3D model of a water treatment plant, projected on my eyes, and over my surroundings. I was in two places at once.

Augmented reality headsets like the HoloLens are hard to describe. The display is transparent, so I was aware of my real-world surroundings, yet still immersed in the 3D projection that was also, in a sense, surrounding me. I could walk around the treatment plant and see the walls. I could even interact with it, drawing in the air or adding notes.

It was a crude demo, without a lot of detail. But Object Theory hopes it will become a useful tool for construction projects. And at least one construction firm, CDM Smith, wants to put it to work. The company focuses on large-scale infrastructure projects, and is convinced that augmented reality will help improve collaboration and prevent mistakes.

Warning: Do not enter without HoloLens

Would you wear a HoloLens on a construction site? Scott Aldridge, leader of CDM Smith’s innovation group, has — and he told Digital Trends that it’s the future.

“Scott looked like an idiot when he was doing this,” joked David Neitz, Chief Information Officer at the company. Kidding aside, Neitz thinks headsets like the HoloLens could eventually become common at construction sites.

“It allows us to collaborate in a way we have not collaborated in the past.”

Aldridge agreed. The group has been experimenting with a variety of virtual reality headsets, from the Oculus Rift to the HTC Vive, in an attempt to imagine their use in designing and refining large-scale construction projects. But augmented reality, which overlays holograms over the real world, could turn out to be uniquely useful.

Aldridge and Neitz ran through the potential uses with me. They could overlay a 3D model of a project over the construction site itself, showing the crew where walls and equipment will be put later.

“Being able to put on a HoloLens and show it to the people who are building the wall, the concrete, the steel, to show them what it will look like before they build it is phenomenal,” said Aldridge.

Another scenario might help in judging whether heavy machinery will work well in a given room.

“You could create a hologram of the large piece of equipment and make sure all the bolt holes line up before you pay for a crane to bring it in,” said Aldridge. “You’d be able to place it wherever it’s going to be put.”

Blueprints are flat, but structures are 3D

Ideas like these see the HoloLens as a practical tool, a sort of hologram-assisted tape measure. And they came up more than once. But what got the team really interested is the potential for collaboration, for speeding up conversations.

Structures are decidedly three dimensional, but for the most part they’re planned out on flat screens, and more commonly flat pieces of paper. According to Neitz, that makes communicating simple ideas complicated.

“We have this challenge with errors, omissions, and change orders, ineffective collaboration that’s occurring between different groups,” said Nietz. “Take a 3D model. It very often becomes a 2D print that loses some of the richness of the data that we’re dealing with.”

The software Object Theory is working on, and CDM Smith hopes to use, attempts to enable better conversations by making sure everyone is looking at the same thing.

“When we started demonstrating it to engineers in the office they were blown away by the potential of it,” said Aldridge. “They see the value of reducing errors and omissions and not having to re-work jobs.”

Hololens helps, because you can’t resize a room

Back in the Object Theory office, I was shown a hologram of a room with a pump in it. But there’s a problem. It was the wrong pump, and the correct one was bigger than the room itself. A wall needed to be moved to make room for the new pump, but moving the wall meant it would overlap with a door in the adjacent room. That door needed to be moved as well, which meant we’d need to re-think the layout of that entire room.

“We want to let people build models as a hologram.”

And so on. Trying to explain it in words is convoluted, which is why so many engineer reports don’t make for a riveting read. But in Object Theory’s demo, the wall was moved to accommodate the bigger pump in just a few moments, followed by the door. I saw what needed to be done, quickly.

“We want to let people build models as a hologram, give them the ability to manipulate the model, let them see different scenarios and solve them right there,” said Aldridge.

The demo is just a starting point. The focus here is collaboration, for the architects, engineers, and on-the-ground crew discussing a potential problem to all be looking at a 3D model together and quickly create solutions.

“It allows us to collaborate in a way we have not collaborated in the past,” said Neitz. “Teams can visualize the environment they’re looking at. It’s pretty powerful.”

Your coworker, the avatar

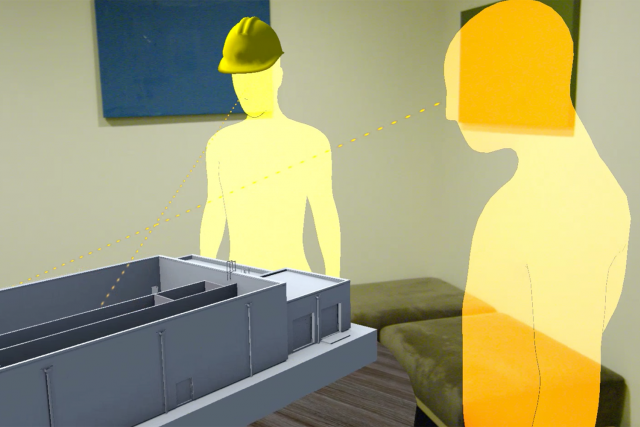

Wearing the HoloLens, I didn’t just see the water treatment plant. I also saw a yellow avatar representing Michael Hoffman, co-founder of Object Theory. When he moved his head, the head of the avatar moved, and when he walked around I could see his avatar moving as well. A line showed me where he his looking.

“The avatars are there because we’re used to talking with humans, not pointers and indicators,” Hoffman told me. “It makes it a much more natural interaction.”

While he spoke about the model, I could tell what Hoffman was looking at because of his avatar. not only because of his head movement, but also thanks to a line that showed me his field of vision. It’s not a complex avatar, but it gets the job done.

Changing the way collaboration happens

A startup veteran, Hoffman has also worked for big companies including Nike and Google. He most recently worked at Microsoft, as part of the HoloLens team.

He’s a true believer in the platform.

“This is a revolution,” he told me. “Microsoft is really knocking this out of the park, I totally believe in what they’re doing, and I have this ability to be an early player as a startup guy in a revolution.”

Hoffman joined up with mobile design veteran Raven Zachary to found Object Theory. The company has been building CDM Smith’s prototype for seven months now. He had a revelation when he discovered how much time he could save with 3D models.

“The aha moment is how efficient it is to have a conversation about a 3D object and know exactly what everyone’s talking about,” said Hoffman.

The team hopes to grow quickly, and they’re particularly interested in convincing game developers to use their 3D modeling skill sets to build practical tools.

https://twitter.com/ravenme/status/715284239810297857

“We tend to find kindred spirits with people who really want to solve big problems,” Amy Hillman, Creative Director at Object Theory, told me. “We think of designs as tools more than entertainment, they’re really meaningful tools that we expect to profoundly change the professional landscape moving forward.”

Leaving a tiger on the table

My HoloLens demo started in a small room with a coffee table and a few chairs. Hoffman talked me through the tutorial, which outlines the gestures necessary to control the device. I threw a hologram of a tiger onto the table before leaving to play Project X-Ray out in the larger conference room.The game was fun, and involved aliens bursting out of the walls around me, but it’s not what blew me away.

No, what impressed me most happened when I returned to that small room: the tiger was still on the table, waiting for me. It’s hard to describe how it felt that I’d “left” that tiger there, in a tangible sense. I couldn’t see it through the walls while outside the room, but approaching the door I could make it out even from a distance. The door frame partially obscured the tiger, just like it would a real-world object, and the tiger grew bigger as I came closer. It was uncanny.

It sounds simple, even mundane, but it clicked for me. I felt the potential, even as I struggled with the HoloLens’ gesture-based control scheme and small field of vision. It’s moments like these that have people so excited about augmented reality.

It’s not at all clear whether the sort of collaboration Object Theory is working on will ultimately prove itself useful. It’s not even clear to CDM Smith that the HoloLens will ultimately be the device they end up using most: the company is currently researching several devices, including the Oculus Rift and the HTC Vive. But whatever happens, virtual reality and augmented reality have the potential to change things well beyond gaming.

CDM Smith, meanwhile, is looking to make an even bigger leap.

“We think we’re going to become a digital company,” Neitz said.

A company that literally works with brick and motor wants to think of itself as digital. Maybe this is a revolution.