At first glance, the Dutch band Light Light might seem like an unlikely source for a viral Internet phenomenon. After all, they’re literally underground (members of the band rehearse in an old bomb shelter). The musicians, who describe themselves as a mixture of “sleazerockers and folk noir minimalists,” previously had a modest but dedicated local following.

At first glance, the Dutch band Light Light might seem like an unlikely source for a viral Internet phenomenon. After all, they’re literally underground (members of the band rehearse in an old bomb shelter). The musicians, who describe themselves as a mixture of “sleazerockers and folk noir minimalists,” previously had a modest but dedicated local following.

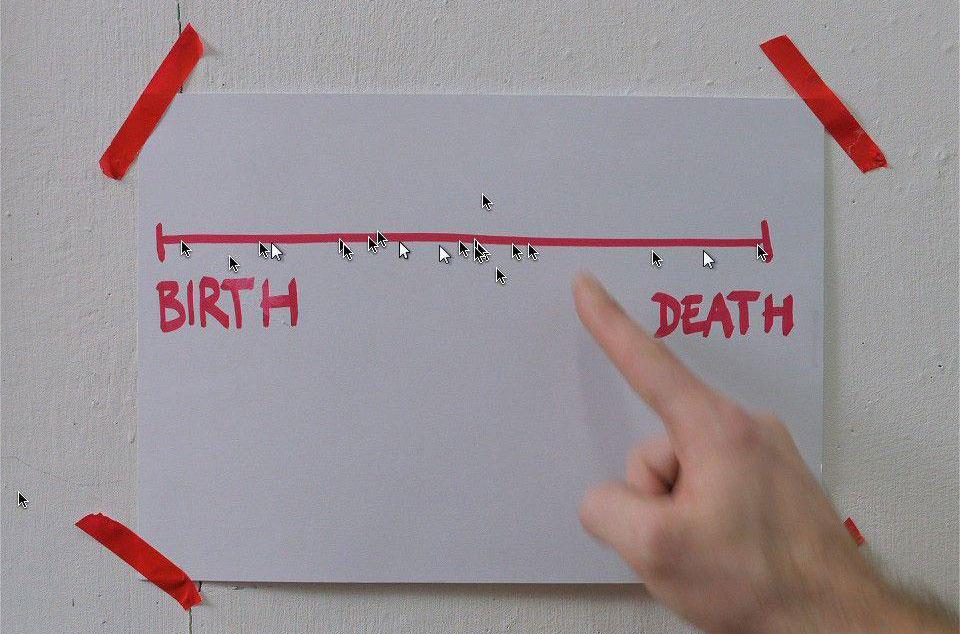

All that changed after Light Light decided to collaborate with design studio Moniker. Inspired by the decline of the mouse pointer in favor of the touchscreen, Moniker’s designers developed the Do Not Touch project for “Kilo,” the first track from Light Light’s recent EP. Launched April 15, the Do Not Touch project – part crowdsourced music video, part interactive website, and part art film – took the Internet by storm. By now, it’s garnered more than two million participants from around the globe.

We covered the Do Not Touch project back in April, but here’s a quick recap: As the website loads and the music begins, you’re informed that your cursor will be tracked. Then, after answering questions such as “Where are you from?” by pointing at a map, you’re directed through a series of tasks, including following a green pathway and forming a smiley-face. The website’s interface simultaneously displays your own cursor alongside the cursors of the last 3,000 to 4,000 people to visit the site, creating a fascinating collective experience.

We were still curious about this interactive meld of art, music, and tech, so we chatted with members of both Moniker and Light Light to get a glimpse into the creative insight, the “end of the cursor,” the transformation of touch technology, and what it’s like being a musician in the ever-evolving digital age.

Drawing inspiration from obsolescence

Jonathan Puckey, a designer and programmer for Moniker – along with Roel Wouters and Luna Maurer – claimed that the inspiration for the Do Not Touch project came from the idea of the cursor becoming obsolete. “Touch devices are the first devices that made me feel a little bit old, or that made me feel part of another generation,” Puckey said.

After all, without a mouse pointer, Puckey could no longer indulge in his favorite aimless habits on the computer. “When I’m working, I often move the cursor to the music,” Puckey said. “When I’m bored, I select my icons, and then I deselect them.” With the rapid rise of tablets and touchscreen monitors, these familiar gestures could gradually fade into the realm of memory. Perhaps it’s no surprise then that Moniker would want to make a tribute video to the unique sensation of using a mouse pointer.

The music video as interactive phenomenon

For Moniker, part of the fun of the project lay in challenging the concept of a music video altogether. “People know what the music video is,” Puckey said. “It has borders, let’s say … and you can play with those borders, you can push it in different directions.” Having previously worked on the collaborative music video One Frame of Fame and the website Pointer Pointer, which also involved a self-aware focus on the cursor, Moniker aspired to something even more ambitiously interactive for Do Not Touch. “We can activate the viewer,” Puckey said. “We want them to become part of the project”.

Alexandra Duvekot, a singer for Light Light – along with bandmates Daan Schinkel, Björn Ottenheim, and Thijs Havens – agree with this vision wholeheartedly. After all, as she pointed out, the thrill of a crowdsourced music video is that you can be in the music. “I think if you make it interactive, you can really reach [people on the Internet], instead of them just being an image on the screen,” Duvekot said. In the end, Do Not Touch attracted an unexpected range of participants, from military personnel to tech geeks.

Lighting up the world map

The Do Not Touch project spread across the globe in surprising ways. Since the website only displays its most recent users, when it asks participants to point toward their home country on a map, the results change drastically depending on the time of day. For instance, when it’s morning in the Netherlands, America blazes bright; around noon, Europe picks up the pace; and more recently, afternoons show a huge buzz in Russia – in this case, thanks to VKontakte, the Russian equivalent of Facebook.

Of course, this international fame also exposed certain cultural differences. Many Americans complained about a nude model in the video being NSFW. Puckey explained that the idea never occurred to Moniker. “We were interested in the idea of self-censorship,” he said, meaning who would “touch” the model with their cursor and who would abstain. Meanwhile, the world map also revealed discrepancies in online access. “It really shows where people come from who actually are able to get on the Internet,” Duvekot said.

Making the unseen visible

For Duvekot, one of the greatest aspects of the crowdsourced music video is that it allows bands like Light Light to interact more personally with their fans, even in the digital age. “As a musician, you cannot do without the Internet nowadays,” Duvekot said. “Sometimes it’s annoying that you actually don’t know who you’re communicating with … So it’s nice to have something being visible,” even something as small as a cursor, she added. “It’s like you make the unseen present.”

Moniker and Light Light hope to make a high-resolution version incorporating hundreds of thousands of cursors…

However, Moniker also hid some secrets purposefully within the Do Not Touch website (shhh … don’t tell!). “When you go to the JavaScript console, the backend of the browser, we put a hidden story for people who are looking at the code,” Puckey said. In addition to this Easter egg, Moniker also cleverly hid a call for new programming interns in the code itself, which drew around 30 applicants.

The meaning behind the mouse

By claiming the video celebrates “the nearing end of the computer cursor,” Moniker asks us to reconsider what it means to use a mouse in the first place. “The cursor is so in plain sight that you miss it,” Puckey said. “It becomes invisible again.” More than that, the cursor represents a very personal aspect of computing, a kind of extension of the self. “It’s you in the digital realm,” Puckey added.

Duvekot agreed, reminiscing about identifying with her own cursor. “I used to turn it into crazy objects when I was little,” she said. “I had a rabbit I really liked: the back of my screen was the stars and the moon, and I had the rabbit flying around in the sky,” she explained.

Perhaps understandably, then, the video’s use of the cursor often provoked personal reactions. “A lot of people were saying they became emotional … People were saying they felt part of a group, a community,” Puckey said. Of course, some users preferred to go rogue, drifting aimlessly or making circles in a corner of the screen. Puckey saw the positive in this as well. “We really enjoy the people who totally don’t do what we ask of them,” especially given the online tendency toward groupthink, he said.

A touchscreen revolution

Of course, just because we might lose the personal cursor doesn’t mean that touch devices aren’t intimate in their own way. “The cursor was like another generation that didn’t really dare to touch each other,” Puckey said, comparing old-school computing with a kind of old-fashioned prudishness. “In my generation, we only pointed at things … I can imagine our children, or our children’s children, touching their devices in such a fine way that we are unable to do,” he added.

“Do you think these devices will replace us?” Duvekot asked, wondering aloud about the relationship between humans and computers in the years to come. “I don’t know if the hardware will replace us, but the future will,” Puckey answered.

The “gray zone” of the future

On the other hand, despite the expressive and artistic potential of touch devices, Puckey and Duvekot are both quick to point out the more ambivalent aspects of new technology. “It’s a bit scary,” said Duvekot, citing the emergence of drone-mounted cameras. “You have a lot of information about other people through hardware … And I think that people will actually not be aware of that.”

Puckey, whose repetitive stress injury makes him acutely aware of the damage a mouse can already do, pointed out the moral ambivalence of the Do Not Touch project itself, especially the group behavior it provokes. “It’s a very gray area for us, and we kind of like it because of that,” he said. “We don’t see it as only one big positive thing … Okay, we’re in a group now, but is that a nice thing? Or is it odd that I’m doing the same thing as this huge crowd?” he said.

Looking ahead: new intersections of art and tech

Overall, however, both Puckey and Duvekot remain optimistic about the creative projects that new technology enables them to explore. For instance, although the Do Not Touch website only displays a few thousand of the most recent participants, Moniker has stored the input from everyone who has ever visited. Soon, Moniker and Light Light hope to make a high-resolution version incorporating hundreds of thousands of cursors, which they would then screen at film festivals. “If you were a listener who participated, you’re gonna be an actor too!” Duvekot said. “It’s going to be on the big screen.”

When it comes to the more distant future, Puckey doesn’t believe in dreaming small. “They promised me a flying car,” he said. Not to be outdone, Duvekot revealed that she hoped for a machine that would allow her to “talk to plants,” as she put it. “I would like to communicate with more species than the Internet user,” she added.

In any case, whether you believe the cursor will soon disappear from the computing world, it’s clear that considering the possibility has enabled these artists to create some amazing digital work together.

(Images and video © 2013 Light Light)