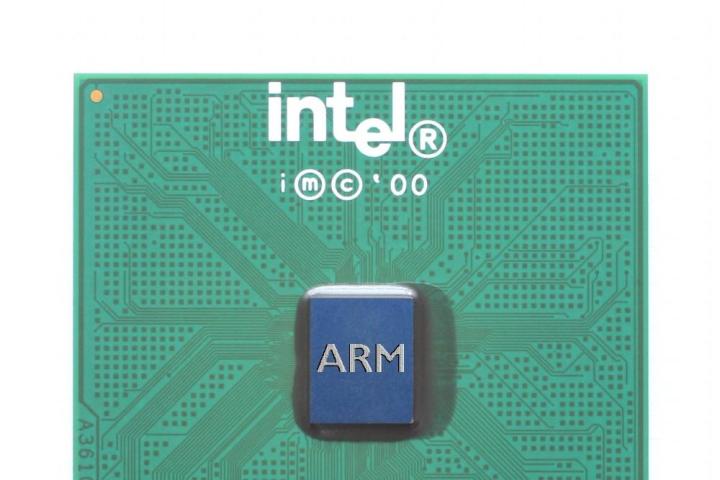

In late October, the unthinkable happened. Intel revealed it was going to build ARM processors.

Much screeching, yelling and boasting followed, led by a Forbes article stating the development has “sent shockwaves through the technology industry.” This is, undoubtedly, a bit of an exaggeration, if only because the scale of the production Intel has agreed to is quite small.

The move does raise obvious questions, though; at first glance it appears that Intel is producing chips that would compete against its own products. A closer look, however, reveals that the situation is more complex, and this move is beneficial for both Intel and consumers.

What do ARM processor designers get out of this?

Intel is known for producing the world’s most advanced consumer processors, and that’s possible largely because the company also owns some of the world’s most advanced fabrication facilities. The company produces its latest chips on a 22 nanometer “tri-gate” production line that uses three-dimensional transistors to improve efficiency. Other fabrication companies, like GlobalFoundries (created when AMD spun off its production division) and TMSC, struggle to keep up with Intel’s pace.

Since production is directly linked to how small and efficient a chip can be, anyone with access to it has an edge. One of the chips, a 64-bit Cortex-A53 processor designed by Altera, a company that creates custom hardware for specialized devices, will be produced on the latest 14nm process, which won’t even be used by Intel until its 5th-gen Core processors are released. Competitors won’t be able to keep up, unless they too sign on with Intel, because (barring any large, unexpected delays) no one else will be producing 14nm chips by the time Intel is sending those chips out the door.

What does Intel get out of this?

The downturn in PC sales has left Intel with some unused production capacity and an apparent desire to diversify. Intel execs have made occasional off-the-record remarks about negotiations with ARM chip designers (most notably Apple) over the last year. Now that such talks have become reality, it’s clear that Intel’s goal is to maintain its famously high profit margins.

That’s important for Intel (and, ultimately, for consumers) because the company relies on research of new technology to drive itself ahead of competitors. New Pentium, then Core, processors have been released about every two years on average. That’s been a huge boon for PCs, as the performance delivered by Intel has roughly doubled over the last five years. But the research and development of a new processor architecture isn’t cheap, so Intel needs to make sure its profit margin has plenty of padding.

Nay-sayers might also remember that Intel is not throwing open the gates of its fabrication facilities and welcoming everyone in. The only two contracts revealed so far are for chips that have very specific jobs. The impressive 14nm, 64-bit Cortex-A53 chip produced by Altera is not going to show up in an Android tablet anytime soon, and doesn’t significantly compete with x86 processors. Intel has expressed a desire to take on more contracts, but it will no doubt be picky about who it will deal with.

What do you get out of this?

Directly, not much. If Intel is unwilling to make deals with manufacturers of consumer-grade ARM processors, which seems to be the case, then the new deal isn’t going to have much of an impact on smartphones and tablets, at least not directly.

Indirectly, these developments might actually strengthen Intel, making it more likely that you’ll see Intel x86 processors in your next mobile device. Why? First, selling production capacity to non-competitive chip designers simply puts more money in Intel’s already formidable war chest. And second, making ARM chips will make Intel engineers even more familiar with both the ARM competition and the production of small, efficient processors. Agreeing to build a 14nm ARM chip alongside its own x86 products may seem strange at first glance, but its effect will be to give the company real-world experience manufacturing a processor architecture used by competitors.

And then there’s the less likely (but possible) alternative future in which Intel decides to design its own ARM chips. If Intel ever did decide it’s in its best interest for your next smartphone to sport an ARM chip – just so long as it is Intel’s – then production experience with the architecture wouldn’t hurt.

Whatever Intel’s long-term strategy, it could be beneficial for consumers if its mobile chips became more competitive. With Apple and Samsung designing for their own devices, the number of companies making top-shelf hardware to third-parties is rather small. A strong new competitor in the segment – particularly one as large as Intel – could help third-party manufacturers keep up with the fantastic chips coming out of Apple and Samsung labs and (exclusively) into each company’s products.

Conclusion

Intel’s decision to produce ARM architectures is not an admission of defeat. The company is not getting in bed with the competition, shooting itself in the foot, or insert business-y cliché here. In fact, this is a simple decision that keeps Intel’s production facilities running, which is undoubtedly a good thing for everyone. Especially you, if you have any plan to buy a new computer in the next five years.

Over the last few years, PC buyers have enjoyed doubled battery life alongside major improvements in both processor and graphics performance, all courtesy of the beast called Intel. To continue enjoying these perks, the beast must be fed. Producing ARM chips on Intel fabs is just a new way to shove more money into the ever-hungry jaws of research and development.