A swift boot

Before Intel Optane, which is based on the 3D Xpoint technology, users had to decide between the two different types of storage device. You could choose a larger spinning disk drive, or HDD, with slow speeds but a good price per gigabyte, or a flash-based SSD with a fraction of the storage space, but five to fifteen times faster performance. System builders often include both, loading the operating system and important software onto the faster SSD, and using the slower HDD as a data drive. This solves one of the biggest issues with HDDs — slow boot times.

Intel should be trying to explain to users why their next PC off the shelf at Best Buy needs Optane

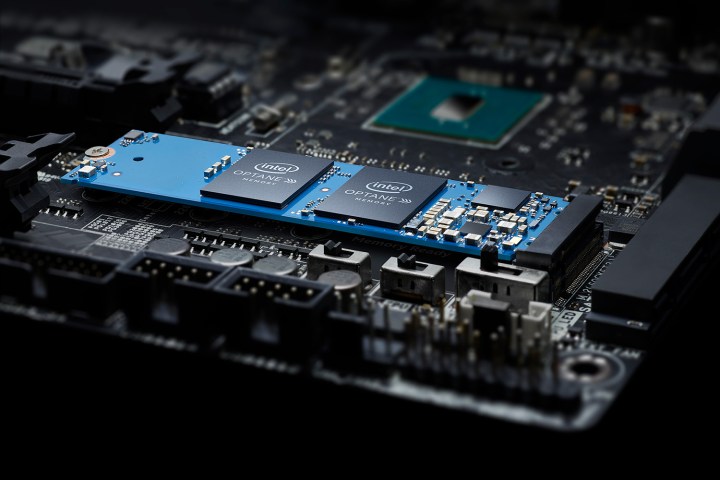

The Optane drives are much faster than even the increasingly common NVMe SSDs, but the Intel Optane Memory isn’t meant to replace those. Instead, you can install the Optane Memory alongside just an HDD, and it will continually monitor your system usage, keeping important files, system libraries, and essential OS pieces cached to the Optane Memory. The software you use most will launch faster, and the break-in period where your system learns what that is shouldn’t take very long.

It’s not the first time manufacturers have developed similar solutions. When SSDs first rolled out and prices were steep, brands pushed out drives that paired up larger HDD-based storage with a small SSD cache in one drive. To a certain extent, it works, but the caching software never really picked up that much speed, except on boot, and you couldn’t prioritize files by hand. Intel claims that driver-level and software optimization allows for seriously improved speeds, although it’s still a hands-off approach.

The right idea, the wrong crowd

The ideal use case for the Intel Optane Memory would seem to be breathing new life into older systems that lack SSDs. Unfortunately, only Seventh Generation Intel Processors actually support Optane, and they’ll also need an M.2 slot to take advantage, which is much more likely to show up on enthusiast motherboards than the specifically manufactured motherboards in off-the-shelf systems. As such, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to upgrade to the Intel Optane Memory unless you just bought a system in the last few months, in which case, you should’ve gone with a full SSD or combination solution.

It’s also tough to stomach the price, at least for system builders, where Intel seems to be targeting these drives initially. The 16GB version will run you $44, while the larger 32GB version, which Intel recommends for power users, costs a full $88. Meanwhile, 250GB SSDs are regularly available for less than $80. Intel says there’s value in not having to manage those files on your own, but it’s hard to imagine that’s much of an ask for someone building a system component by component.

If anything, it’s likely that Intel Optane Memory will slow SSD adoption in pre-built consumer machines. OEMs typically buy in bulk for better pricing, and Intel Optane Memory allows those system builders to keep using those stacks of slow-ass 5400RPM drives that are taking up space on shelves instead of moving on to dedicated SSDs. Pre-built computers with Optane Memory should start hitting shelves on April 24th, with pre-orders for individual users starting today and shipping at the same time os OEM machines.

A lot of promise

It definitely feels like Intel is on to something here, for the simple reason that most computer users look for the larger hard drive. It’s one of the most important factors to the casual user, and they definitely notice when storage space is lacking. What system builders know is that using an SSD improves the minute-to-minute usability and responsiveness of any system, to the point that we’ve taken to harshly criticize modern systems that don’t at least offer it as an option.

The bottom line is that Intel is offering up a product that makes some impressive promises to a market that already had to answer them. Intel shouldn’t be trying to sell Optane Memory as a way to increase the responsiveness of high-end PCs, which are almost all sporting at least an SATA SSD already. Instead, it should just be trying to explain to users what Optane is, and why their next pre-built system off the Best Buy shelf should have Optane. We’ll withhold final judgement until we’ve spent time with the drive in our test lab, but for now, we remain skeptical.