Cybersecurity researchers have discovered a new zero-day vulnerability that has surfaced in Microsoft’s Exchange email servers and has already been exploited by bad actors.

The yet-to-be-named vulnerability has been detailed by cybersecurity vendor GTSC, though information about the exploit is still being collected. It is considered a “zero-day” vulnerability due to the fact that public access to the flaw was apparent before a patch could be made available.

https://twitter.com/GossiTheDog/status/1575580072961982464?s=20&t=xLnNnGRTl3AA1Qb5EEgNGQ

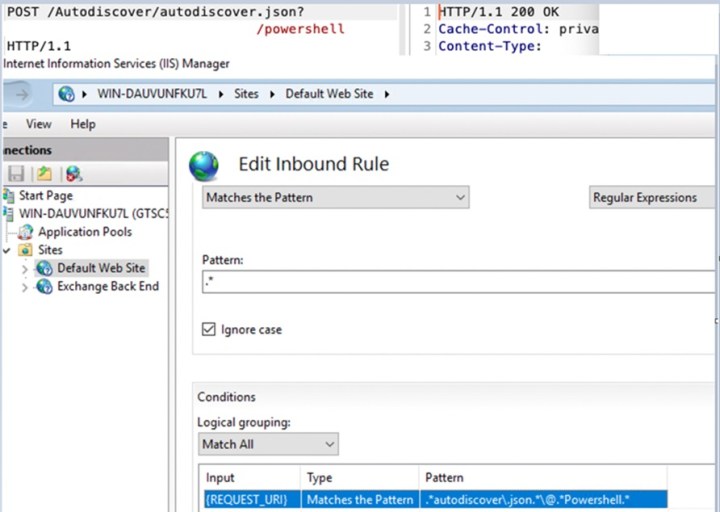

News of the vulnerability was first submitted to Microsoft through its Zero Day Initiative program last Thursday September 29, detailing that the exploits of malware CVE-2022-41040 and CVE-2022-41082 “could allow an attacker the ability to perform remote code execution on affected Microsoft Exchange servers,” according to Trend Micro.

Microsoft stated on Friday that it was “working on an accelerated timeline” to address the zero-day vulnerability and create a patch. However, researcher Kevin Beaumont confirmed on Twitter that the flaw has been used by nefarious players to gain access to the back ends of several Exchange servers.

With the exploitation already in the wild, there are ample opportunities for businesses and government entities to be attacked by bad actors. This is due to the fact that Exchange servers rely upon the internet and cutting connections would sever productivity for many organizations, Travis Smith, vice president of malware threat research at Qualys, told Protocol.

While details of exactly how the CVE-2022-41040 and CVE-2022-41082 malware work is not known, several researchers noted similarities to other vulnerabilities. These include the Apache Log4j flaw and the “ProxyShell” vulnerability, which both have remote code execution in common. In fact, several researchers mistook the new vulnerability for ProxyShell until it was made clear that the old flaw was up to date on all of its patches. This made it clear that CVE-2022-41040 and CVE-2022-41082 are completely new, never-before-seen vulnerabilities.

“If that is true, what it tells you is that even some of the security practices and procedures that are being used today are falling short. They get back to the inherent vulnerabilities in the code and the software that are foundational to this IT ecosystem,” Roger Cressey, former member of cybersecurity and counterterrorism for the Clinton and Bush White Houses, told DigitalTrends.

“If you have a dominant position in the market, then you end up whenever there’s an exploitation you think you’ve solved but it turns out there are other ones associated with it that pop up when you least expect it. And exchange is not exactly the poster child for what I would call a secure, a secure offering,” he added.

Malware and zero-day vulnerabilities are a fairly consistent reality for all technology companies. However, Microsoft perfected its ability to identify and remediate issues, and make available patching for vulnerabilities in the aftermath of an attack.

According to the CISA vulnerabilities catalog, Microsoft Systems has been subject to 238 cybersecurity deficiencies since the beginning of the year, which accounts for 30% of all discovered vulnerabilities. These attacks include those against other major technology brands including Apple iOS, Google Chrome, Adobe Systems, and Linux, among many others.

“There are a lot of technology IT companies that have zero days that are discovered and are exploited by adversaries. The problem is Microsoft has been so successful at dominating the marketplace that when their vulnerabilities are discovered, the cascading impact that it has in terms of scale and reach is incredibly big. And so when Microsoft sneezes, the critical infrastructure world catches a bad cold and that seems to be a repeating process here,” Cressey said.

One such zero-day vulnerability that was resolved earlier this year was Follina (CVE-2022-30190), which granted hackers access to the Microsoft Support Diagnostic Tool (MSDT). This tool is commonly associated with Microsoft Office and Microsoft Word. Hackers were able to exploit it to gain access to a computer’s back end, granting them permission to install programs, create new user accounts, and manipulate data on a device.

Early accounts of the vulnerability’s existence were remedied with workarounds. However, Microsoft stepped in with a permanent software fix once hackers began to use the information they gathered to target the Tibetan diaspora and U.S. and E.U. government agencies.