The original Raspberry Pi, a $35 computer released in early 2012, spurred a revolution in computing. For the cost of a bar tab, an inventor, programmer or gamer could pick up a Pi and customize it to do … well, whatever they wanted. Though not the first hobbyist computing board available, its broad base of support and ability to run variants of common Linux distributions made it more accessible and capable than many predecessors.

Despite its success, the original Pi was essentially limited to curious and inventive geeks. Its modest, single-core ARM chip slogged through many common tasks painfully slow. Even simple Web pages took a long time to load and, once open, suffered stutter-start scrolling. While usable as a computer in theory, the Pi wasn’t great in practice.

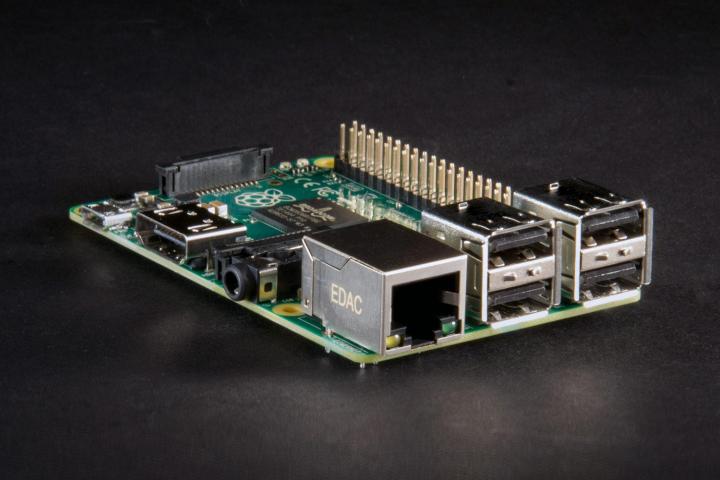

The sequel, the Raspberry Pi 2 is a major upgrade. The single-core 700MHz processor has been upgraded to a 900MHz quad-core chip, and RAM has quadrupled from 256MB to 1GB (the Raspberry Pi Model B, which arrived in late October, had 512MB).

Does this mean the Pi 2 is usable as an everyday computer, or is it still for projects only?

Getting started with Pi

The Raspberry Pi has always appeared more approachable than it is. The $35 price tag itself is arguably deceptive, as it doesn’t include what’s needed for the device to operate. There’s no power adapter, no microSD card, not even a case. All of that must be purchased individually.

This is not a plug-and-play device

How much does it really cost to start with the Pi 2, then? We snagged a power adapter for $9, a 16GB microSD card for $8, and a mouse and keyboard combo for $15. A case is another $8, though we went without. All told, then, the final price (without monitor) is around $75. Not bad, for sure, but more than double the $35 MSRP that makes headlines.

We set up our Pi 2 with the standard NOOBS installation image. Users can purchase a card with it pre-installed for maximum simplicity, but we imaged our microSD card ourselves. The process took about 20 minutes, most of which was spent writing files to the card. Once transferred, starting the Pi for the first time proved as simple as connecting cords and providing power (there’s no power button; the system boots automatically once connected). A few clicks later, and the Raspbian desktop appeared.

If that were the end of setup, we’d have nothing but praise, but the tale continues. Raspbian comes with only a few programs installed, and while they’re supposed to provide all the basic functionality needed, they often prove inadequate. The Pi Store, for example, is a bit of a mess; beyond the fact it’s hard to navigate, it never actually succeeded in installing and launching a single application. That meant we had to move on to using terminal commands, such as “sudo apt-get install libreoffice-writer” to load software. Not rocket science, but certainly more difficult than it appears at first glance.

Other bugs included improper detection of our monitor’s native resolution, a DNS issue that made the Internet unusable with the particular switch we originally tried to use, and disappointing performance from the default Web browser. We bypassed these problems in a variety of ways, but resolving those issues took several frustrating hours. This is not a plug-and-play device.

Daily driver

Once set up, we started to use the Raspberry Pi 2 for all the things anyone might use a computer for. Web browsing. Document creation. Image editing. And for the most part, the new Pi proved surprisingly capable.

Let’s start with browsing, the most common activity. The base browser, Midori, is allegedly “lightweight,” but it didn’t feel nimble. We replaced it with Chrome. So equipped, most webpages loaded in seconds, and scrolling was smooth more often than not, with some notable exceptions. Amazon.com, for example, was a bit of a bear. Navigating the site took patience as page elements often failed to respond immediately, and instead required several seconds to process.

Despite the Pi’s limited performance, we encountered no problem with Writer, Calc or Impress.

Oddly, some Web services we expected to be problematic worked well enough. Google Drive warned us that the Pi’s installation of Chrome might not work, but was responsive. Microsoft’s Word Online worked too, with all its features. We used the Pi 2 to edit comments and collaborate in real-time with colleagues. The limitations of the 900MHz processor sometimes appeared in the form of delayed text or jerky scrolling, but we were able to accomplish everything we required.

If productivity is your goal, though, LibreOffice is the way to go. This free, open-source alternative to Microsoft Office has become the Office alternative of choice. Despite the Pi’s limited performance, we encountered no problem with Writer, Calc or Impress, (this entire review was authored on the Pi). A complex document might slow the Pi 2, but no one is buying this under the impression it’s a workstation.

We were further surprised by how well the Pi 2 handled GIMP, a robust open-source image editing utility similar to Photoshop. We opened 720p and 1080p images and performed a variety of tasks, such as scaling, applying filters and cropping. While certain complex actions required several seconds to complete (almost everything is almost instant on a modern Windows PC) the overall experience was far more competent than the specifications would have you believe.

Pushing the limits

Anyone with a modest level of technical understanding and the patience to Google the problems that will inevitably crop up can use the Raspberry Pi 2 for the holy trinity of Web browsing, document creation and image editing. But there are limits.

Web browsing is the activity most likely to expose the system’s limitations. Modern websites are coded for a world of readily available compute power and auto-updating browsers. The limitations of the Pi 2 aren’t difficult to find; just load YouTube.

By default, the Pi’s browser can’t play YouTube at all. The currently available version of Chrome can’t, either. We did find a browser, called Minimal Kiosk Browser, that can, but it’s hardly ideal. Its finicky and outdated interface felt like something straight from the 1990s, and while video playback was smooth even at 1080p, it wasn’t reliable. We ran into YouTube’s “static screen” error numerous times.

Games are also well outside the capabilities of the Pi. Flash can’t be installed in any of the major browsers available for the system, which is why the Minimal Kiosk Browser is required for YouTube. That alone eliminates numerous Web games from the list of possibilities. Standalone titles are a rarity, as well, because there’s nothing about the Pi 2 that makes it an attractive platform for a game developer. It is possible to turn the system into an emulator (even the original Pi was adept at that) but there’s essentially no new content to keep you entertained, and many of the emulation platforms for the original Pi are still in the process of coding support for its successor.

Clearly, entertainment isn’t the system’s forte, but there are boundaries to productivity as well. Video editing is essentially out of the question. Hardware limitations aside, there’s no software that can handle the task, so it’s literally impossible. Other tasks that are difficult or impossible on the Raspberry Pi 2 include .PDF editing, managing large spreadsheet and database files, developing Web pages with advanced page elements (like HTML5), and using many common cloud services, such as OneDrive or Evernote, which lack compatible clients.

More than a hobby?

The Raspberry Pi 2 mostly delivers the minimal level of functionality a computer needs to be useful, and it does so at an all-in, brand-new cost of about $75, not counting a display. If you don’t mind shopping second hand, it’s be entirely possible to start using the Pi 2 for less than $100.

The Pi is less of a revolution, and more of a toy.

Unfortunately for the Pi 2, though, there’s a third way: a used Windows PC. We didn’t have to look hard to find a number of notebooks and desktops with Windows 7, two to four gigabytes of RAM and up to 160 gigabytes of long-term storage. You can find these systems locally or online, and although the total cost will be a bit higher than the Pi 2 with accessories included, the resulting system will be far more capable.

That means the new Raspberry Pi, despite all the goodness it bakes into its tiny footprint, is still a platform for hobbyists and inventors. It doesn’t drastically lower the barrier to entry for people without money to spend, because more capable devices are already available, albeit used. The Pi is smaller, to be sure, but for users on a budget size is almost irrelevant.

Tinkering with the Pi is a great way to familiarize yourself with Linux, learn to program Python, or become acquainted with ARM as an architecture. But it’s still not the obtainable, pocketable PC it’s sometimes portrayed. Support for Windows 10, when it comes, will be a step down that path. For now, though, the Pi is less of a revolution, and more of a toy.