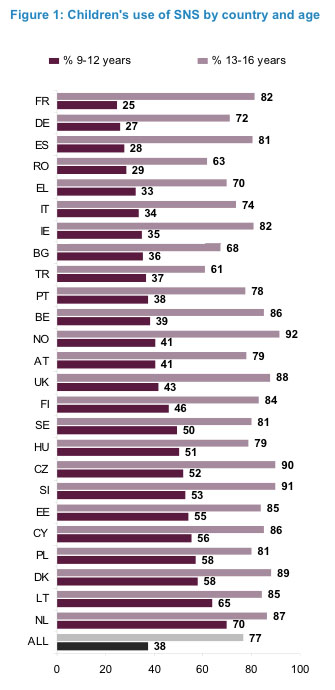

A new report (PDF) from the EU Kids Online at the London School of Economics finds that age restrictions designed to keep young children off social networking sites are not particularly effective. The survey polled some 25,000 young people across Europe and found that, on average, 38 percent of respondents aged 9 through 12 use social networking sites, and one in five has a profile on Facebook. In some countries, the proportions are higher: for instance, 38 percent of British children surveyed aged 9 through 12 have a profile on Facebook. The study also found that over than a quarter of those 9-12 year-olds have their profiles set to fully public, so they are viewable by anyone in the world.

“It seems clear that children are moving to Facebook&mdash,this is now the most popular site in 17 of the 25 countries we surveyed,” said EUKidsOnline director Sonia Livingstone, professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, in a statement. “Many providers try to restrict their users to 13-year-olds and above but we can see that this is not effective.”

Averaged across all 25 European countries included in the survey, children aged 9 to 16 indicated a strong gravitation towards Facebook, with 57 percent of respondents using Facebook as their primary or sole social networking site. However, there were significant variations by country: in Poland, for instance, only two percent of respondents considered Facebook the center of their social networking universe. In Cyprus, however, the figure was 98 percent.

The survey also found that roughly one in six 9 to 12-year olds has 100 or more online contacts, and about one in five 9 to 12 year olds using social networking services have contact with people who have no connection whatsoever to their offline lives. And among those underage users who have their profile set to “public?” ABout one in five have their address and/or phone number out there for the world to see—and twice as many include that information in private profiles visible only to friends.

The study concludes that age restrictions and parental controls for controlling access to social networking sites are ineffective, and that features designed to protect children’s online privacy are not readily understood by young children, or even many older children.

Elisabeth Stroud from the University of Oslo, one of the report’s authors, suggests that age restrictions are merely driving childrens’ social networking use underground, and that a practical solution might be to remove age restrictions and create tools that children can use. “Since children often lie about their age to join ‘forbidden’ sites it would be more practical to identify younger users and to target them with easy-to-use protective measures,” Stoud said in a statement. “However, we accept that abolishing age limits could lead to a substantial rise in the numbers using the sites.”