Apple is one of America’s most successful companies, but it’s also one of America’s biggest financial successes. Apple pocketed $9.5 billion in pure profit last quarter; the company employs over 50,000 people in the U.S. doing everything from R&D to running data centers to selling earbuds in Apple Stores – and Apple claims it’s indirectly responsible for as many as 600,000 other U.S. jobs, ranging from app developers to bloggers who cover the latest Apple rumors. (That’s apparently moved from being a “thing” to a “viable career.”)

Apple is one of America’s most successful companies, but it’s also one of America’s biggest financial successes. Apple pocketed $9.5 billion in pure profit last quarter; the company employs over 50,000 people in the U.S. doing everything from R&D to running data centers to selling earbuds in Apple Stores – and Apple claims it’s indirectly responsible for as many as 600,000 other U.S. jobs, ranging from app developers to bloggers who cover the latest Apple rumors. (That’s apparently moved from being a “thing” to a “viable career.”)

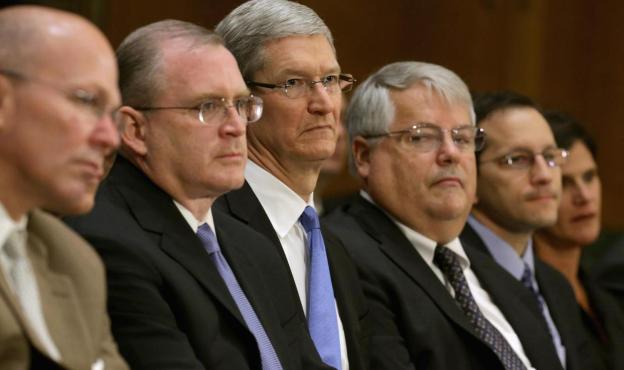

Apple’s economic clout is why CEO Tim Cook, CFO Peter Oppenheimer, and head of Tax Operations Peter Bullock were called to testify before the U.S. Senate’s Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Permanent subcommittee on Investigations. Apple has not been accused of violating any law, but the context of the hearing is that Apple is skipping out on billions in corporate income taxes by stashing money overseas in subsidiaries that, weirdly enough, don’t legally reside anywhere.

Has Apple found a magic recipe for evading the IRS? Or is Apple merely fulfilling its corporate responsibilities to shareholders – and, arguably, not doing all that great a job?

“There’s one for you, nineteen for me…”

First, a little U.S. corporate income tax background. (Don’t worry, it’s quick!) If a U.S. corporation earns over $10 million a year, the federal government imposes a 35 percent tax. That’s basically the highest corporate rate in the world, and state and local taxes added on top push the figure closer to 40 percent. This isn’t new: the basic modern tax system was formed during World War II with corporate tax rules getting their biggest makeover in the 1960s. Back then, corporate income taxes were big bucks, accounting for nearly a third of all federal tax revenue in 1952.

That didn’t last. High rates have always had U.S. corporations looking for ways to pay less. By the 1960s, corporate income tax dropped to 20 to 25 percent of federal tax revenue, and today it’s less than 10 percent.

A favorite tactic has been launching subsidiary companies in places with lower corporate tax rates, then pushing income to those subsidiaries. This defers the U.S. tax, but doesn’t waive it. If the U.S. corporation wants pay employees or put up a new building with that overseas cash, it pays the 35 percent rate first. But if they want to use that money overseas, invest it, or just keep it on the books without paying a dime in U.S. corporate income tax … that’s fine too.

How much money are we talking about? American multinationals have an estimated $1.7 trillion sitting offshore today. Apple alone accounts for over $100 billion of that. Basically, the Senate subcommittee is trying to find ways for the U.S. government to get more of that money, particularly since the U.S. federal debt is now approaching $17 trillion.

Apple’s Irish Pot o’ Gold

What’s Apple’s magic formula? It’s tacky, but one might say “leprechauns.” Over 30 years ago Ireland was suffering a triple whammy of a worldwide recession, a crusading conservative British government led by Margaret Thatcher, and (of course) The Troubles.

How to attract foreign companies to a impoverished country with a long history of political violence? Tax breaks. Ireland recruited Apple with a deal that included a corporate tax rate under two percent. This was 1980, long before the iPod, iPhone, or iPad, or even the Mac. Today, Apple has several Irish subsidiaries, including Apple Sales International (ASI), Apple Operations Europe (AOE), and Apple Operations International (AOI). Apple acknowledges the Irish outfits are run from Cupertino, but they aren’t just paper tigers: Apple now has over 4,000 employees in Ireland handling sales and some operations for Europe, Africa, and Asia-Pacific. They also fund over half of Apple’s R&D efforts in a cost-sharing arrangement in exchange for rights to Apple’s intellectual property: that way, they can sell Apple products in their territories.

Thanks to a deliberate quirk in Irish tax law, managing these Irish companies from Cupertino means two of them aren’t “tax resident” in Ireland – or anywhere.

“Under Irish law, the requirement for evaluating or concluding on the tax residency for Ireland looks to whether central management and control takes place in Ireland or not,” testified Apple’s tax head Phillip Bullock. “It does not require that a determination be made that it takes place somewhere else.”

“That’s the utopian goal that tax planners try to obtain, in which you create an entity that is taxed nowhere.”

“That’s the utopian goal that tax planners try to obtain, in which you create an entity that is taxed nowhere,” said Villanova Law School professor Richard Harvey in testimony before the subcommittee. “Apple, through this particular structure, was able to substantially accomplish that.”

Cost-sharing arrangements with multiple Irish subsidiaries is often called the “double Irish,” and the setup mainly work for companies with patents and intellectual property they can license. Apple’s long-standing arrangement may have been the first to exploit this corner of Irish law, but it certainly wasn’t the last.

That’s not all: Through quirks in the U.S.’s own tax code, Apple can choose to fold up its chain of subsidiaries into a single entity (AOI) for tax purposes. So, when ASI buys iPhones from Foxconn and immediately sells them to (say) Apple Singapore at a markup, that transaction becomes non-taxable from the IRS’s point of view. The same idea applies to other inter-company transactions like dividends and royalties. Overall, the Senate committee reckons Apple has shielded over $44 billion from U.S. taxes – or an average $17 million in tax revenues per day in 2011 and 2012 alone.

Apple’s point of view

Apple doesn’t see its financial setup as tax evasion. “We not only comply with the laws,” testified CEO Tim Cook, “we comply with the spirit of the law.”

It can be argued that, if Apple is a tax evader, it’s not a very good one. Apple believes it may be America’s largest corporate tax payer. In 2012, Apple says it paid over $6 billion to the U.S. Treasury, and expects to pay over $7 billion this year. (Add to that more than $2 billion in payroll taxes, state income tax, and sales taxes.) Overall, Apple calculates its U.S. federal income tax rate in 2012 was 30.5 percent. The income Apple earns in international markets is not tax-free: Apple pays sales, VAT, GST, and/or income taxes in the countries where it operates.

Apple also doesn’t leverage its Irish subsidiaries as efficiently as it could. Revenue from sales in Europe, Africa, and Asia runs through the Irish firms: that’s about 70 percent of Apple’s income. That’s a lot, but it’s not wildly disproportionate: last quarter, 66 percent of Apple’s sales happened outside the United States.

“We do have a low tax rate outside the United States, but this tax rate is for products sold outside the United States,” Cook testified.

Apple itself handles North and South America, and pays the full 35 percent rate on that income. Apple could shift all non-U.S. money to Ireland – including big markets like Mexico, Canada, and Brazil – but has failed to do so after more than three decades. Over half of Apple’s R&D efforts are funded by the Irish subsidiaries, but Apple says it doesn’t deduct those R&D costs on its U.S. tax return.

“We pay all the taxes we owe, every single dollar.”

“(Apple Operations International) is nothing more than a company that has been set up to manage Apple’s cash that has already been taxed,” Cook testified. “From my point of view, AOI does not reduce Apple’s U.S. taxes at all.”

Pot, kettle, black

Most of us struggle to manage our checkbooks, so Irish subsidiaries seem terribly arcane. Nonetheless, Tim Cook is adamant Apple is an American company that is not engaging in gimmicks.

“I don’t consider deferral to be a sham or abusive,” Cook told the subcommittee. “Apple has real operations in real places, with Apple employees selling real products to real customers.”

And, indeed, Apple’s financial setup seems simpler than some of its competitors. Microsoft also has a “double Irish” arrangement, but it’s supplemented by similar strategies out of Singapore and Puerto Rico. Google uses a “double Irish with a Dutch sandwich,” funneling money to Ireland, then the Netherlands (tax-free), then to Bermuda, which has no corporate income tax at all. Amazon and Facebook have similar arrangements for their non-U.S. income. Hewlett-Packard keeps virtually all its money offshore and funds its day-to-day operations through alternating, tax-free, short-term loans from Belgium and the Cayman Islands.

What’s more, some American companies pay no U.S. corporate income tax, often through combinations of clever accounting and manufacturing tax credits. You might recognize a few like Boeing, General Electric, Consolidated Edison, Paccar, and Verizon Communications. Yeah, that Verizon.

Compared to its peers, one could argue Apple has been negligent in reducing its U.S. tax burden – heck, even incompetent.

[Images via Getty, Huffington Post]