Microsoft has updated its minimum system requirements for Windows 11, which doesn’t make a difference for the vast majority of people. The requirements are less strict now, technically, though nowhere near on the level I hoped for or expected. That includes the TPM requirement, which Microsoft is holding firm on.

When Microsoft announced Windows 11, PC enthusiasts were forced to become cybersecurity experts, trying to figure out what a TPM is and why it’s important. Microsoft is offering a solution to that problem for people with recent hardware. Still, it hasn’t addressed the main issue with the TPM and Windows 11. Here’s why.

The enthusiast dilemma

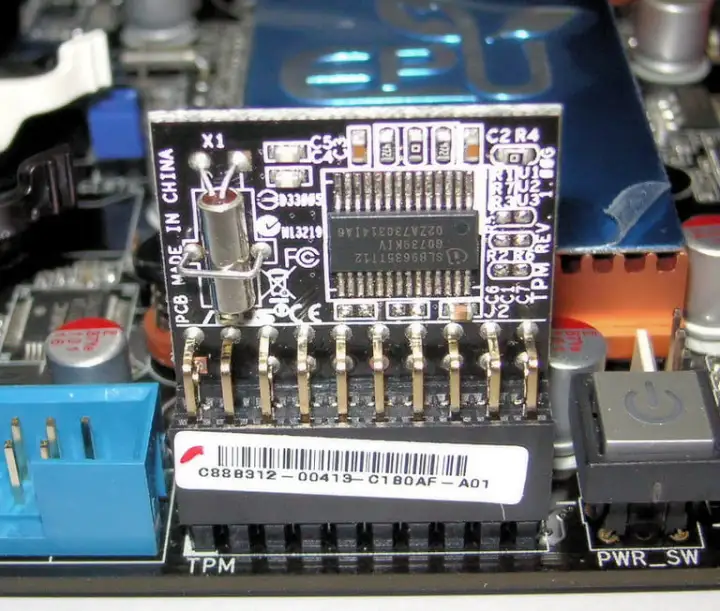

Let’s get some housekeeping out of the way first. The main issue with TPM is that a lot of DIY motherboards don’t come with a chip on board. Microsoft has required PC makers to include a TPM for years, so this conversation doesn’t really apply to prebuilt machines or laptops from the last few years. It’s focused on PC builders that have recent hardware, but not a dedicated TPM chip.

You don’t need a dedicated TPM chip for Windows 11, but Microsoft did a bad job of explaining that. Microsoft’s old PC Health Check app said my gaming PC with a 10th-gen Core i9 couldn’t run Windows 11. It could, but Microsoft didn’t explain that I would need to enable the TPM through firmware.

Needless to say, a media frenzy followed as PC builders were told they couldn’t run Windows 11. Recent motherboards support TPM through firmware, which is less secure than a hardware solution, but still enough to run Windows 11. Now, Microsoft is addressing the issue with an updated PC Heath Check app.

It will now tell users what component isn’t compatible with Windows 11 and link to a support article, including articles about enabling firmware TPM. Microsoft is standing its ground on this requirement, which has been around for PC manufacturers for a few years. There’s a good reason why, but that doesn’t address the problem TPM presented in the first place.

TPM or no TPM

A TPM is simple. It’s a small chip that stores keys to decrypt data and other authentication information. The TPM is notable because it’s set away from the CPU and other components. Even during a catastrophic event when your PC is compromised, no one will be able to crack into the TPM. It’s a vault for secure data, as Jorge Myszne, co-founder and CEO of Kameleon Security, calls it.

The applications of a TPM for most people are Windows Hello and Bitlocker, which aren’t strictly necessary. A strong password still works in place of biometric authentication for Windows Hello, and Bitlocker is only necessary if you want to encrypt your hard drive — and a lot of people don’t. They offer increased security, assuming you use them.

Secure Boot is a different matter. In short, Secure Boot is tied to firmware stored on your motherboard, and checks everything that executes before the operating system loads. To make sure there aren’t any unauthorized programs running, it gains deep access to the software running on your PC. It doesn’t require a TPM.

Windows gives applications access to the TPM, which makes it much more practical. According to Myszne, however, most developers don’t take advantage of it because messing with the TPM has the chance to brick components. “Anything that has to do with VPNs or storing, you know, all the password managers, all those things. It’s exactly the application [that] should be using the TPM, but they don’t use it, right? Just because they don’t want to deal with that.”

Instead, vendors store things like certificates and authentication keys in software, where it’s more vulnerable. That doesn’t mean all software bypasses the TPM, however. Outlook and Thunderbird, for example, use the TPM to handle encrypted email. Still, a lot of software opts to use software instead, rendering the TPM pointless for them.

I don’t want to mince words: Having TPM is better than not having it — it’s just a matter of how much security you need. Once you move from a dedicated TPM module to software TPM, you’re already giving up some security. Windows 11 works with both, but that doesn’t address the problem for people who either have an older version of TPM or not at all.

The TPM problem

There’s a reason DIY motherboards don’t come with firmware TPM enabled: It’s not as secure. Firmware TPM uses the CPU instead of a separate, smaller processor on the motherboard. As the Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities show, the CPU isn’t immune to security compromises, which brings into question why firmware TPM works with Windows 11.

If both hardware and less-secure firmware TPMs work with Windows 11, why have the requirement at all? Microsoft wants increased security, which is something I can get behind, but it doesn’t make sense to meddle in a middle ground. Going hardware only would alienate some of Microsoft’s customers, but the hard requirement on TPM is already doing that.

You need a recent motherboard to use the TPM version Microsoft requires. Most motherboards produced after 2016 fall into that category. Every motherboard vendor is a little different, however, so some started supporting TPM 2.0 shortly after it released in 2014 while others waited until later. Unfortunately, most motherboard makers waited.

That means if you built your PC between 2014 and 2016, the answer to if your PC supports Windows 11 is a depressing “maybe.” If you built your PC before 2014, it’s a hard “no.” Instead, Microsoft has told users with older hardware to just keep using Windows 10, which is an OS that will almost certainly play second fiddle to Windows 11 once it launches.

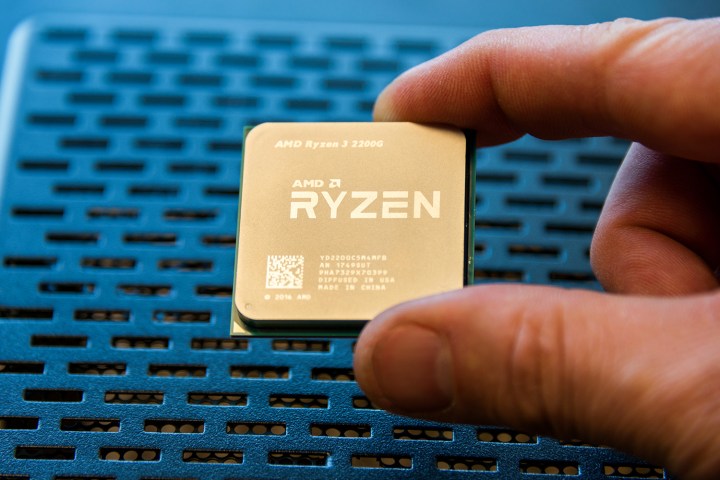

Unfortunately, the conversation around TPM and Windows 11 is largely irrelevant. Microsoft updated its list of supported processors, but failed to add support for many of the CPUs customers were asking for. That includes first-gen Ryzen processors, which released in 2017. If you have a PC you built before 2016, there’s a decent chance it doesn’t support Windows 11 — TPM or not.

The good news is that Microsoft is offering a workaround. If you don’t have a supported CPU, you can still download the Windows 11 ISO and install the OS. Going this route will put the OS in an unsupported state, so it could be subject to more bugs and crashes. For the ISO, all you need is a 1GHz dual-core processor, 4GB of RAM, and 64GB of storage.

Microsoft’s firm stance on TPM sends a message. It’s that Windows is moving in a direction of enhanced security, but at the cost of the “bring-your-own-hardware” mentality the OS has long held. Holding onto Windows 10 or using Windows 11 in an unsupported state are fine solutions for now, but they will run their course before Microsoft ends support for Windows 10 in 2025.