A decade in the making, the findings from a team led by Professor Anthony Atala were published today in Nature Biotechnology, and represent an incredible step forward in the idea of a “plug and play” human being. According to the Wake Forest team, the bioprinter functions much as a “traditional” 3D printer does, making use of additive manufacturing techniques in order to add materials layer by layer, ultimately creating a complex structure. But unlike most 3D printers that use plastics, resins, metals (and sometimes, even ceramics), these bioprinters use very different materials.

Bioprinters work the same way that conventional 3D printers do, using additive manufacturing to build complex structures layer by layer. Instead of using plastics, resins, and metals, however, bioprinters use special bio-materials that closely approximate functional, living tissue.

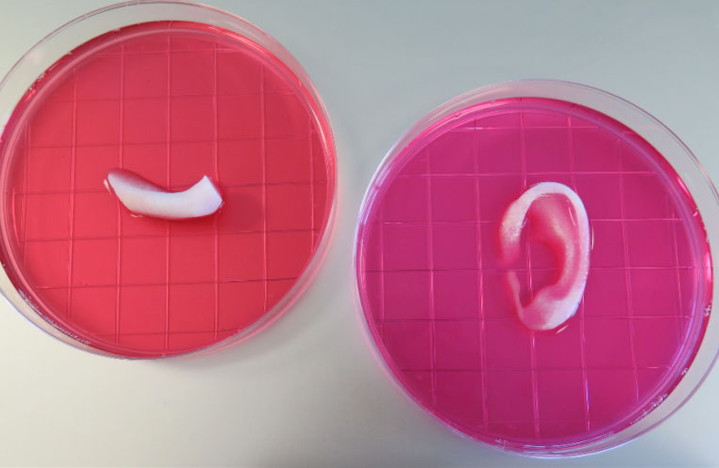

Once the Integrated Tissue and Organ Printing System (ITOP) is further tested, and has been proven to be safe for use in humans, we could soon be printing out replacement body parts for patients.

“Cells simply cannot survive without a blood vessel supply that’s smaller than 200 microns [0.07 inches], which is extremely small,” Atala told Gizmodo. “That’s the maximum distance. And that’s not just for printing, that’s nature.”

But the ITOP addresses this issue by using polymer materials in order to create the shape of the structure, and then a water-based gel sends cells to the right place within this structure. An outer structure is temporarily implemented in order to help the cells keep their shape during the printing process, and researchers also place microchannels directly into the design that allow for nutrients and oxygen to be delivered to the cells. “We basically recreated capillaries, creating microchannels that acted like a capillary bed,” explained Atala.

From the looks of things, Atala and his team have a good thing going — the tissues look to be correctly sized, shaped, and of the proper strength for actual use in human bodies, but they’re still undergoing more tests to be extra safe. And more exciting still, they’re looking at other applications of ITOP as well.

“Future development of the integrated tissue-organ printer is being directed to the production of tissues for human applications, and to the building of more complex tissues and solid organs,” Atala told Quartz. “When printing human tissues and organs, of course, we need to make sure the cells survive, and function is the final test. Our research indicates the feasibility of printing bone, muscle, and cartilage for patients. We will be using similar strategies to print solid organs.”

And while Atala says that “It’s still going to be a while” before this can be called a major breakthrough, that just might be the understatement of the decade.