A thin line separates science from art. It’s often blurred. When scientists employ an artist’s creativity, imaginatively theorize the unimaginable — as Newton, Einstein, and Hawking were able to do — they’ve been known to make discoveries worth hanging on gallery walls. When artists apply methodological rigor to their work, they have a chance to illuminate the seemingly inaccessible aspects of science. Da Vinci, Dalí, Stelarc — each was an artist with a scientific frame of mind.

Two new imaging techniques developed by researchers at the University of Kansas (KU) blend science and art in a hauntingly captivating way. The techniques allow for photos to be taken of 50-plus-year-old vertebrate specimens, depicting the intricacies of their anatomy. Among the specimens imaged were a shrew, python, and viperfish.

The first process entails using “cleared and stained” specimens that have been stripped of their muscles. With their muscles removed, specimens go flaccid and don’t hold their natural shape. The KU researchers’ breakthrough was to place them in a translucent glycerine-gelatin mixture, such that they could pose the specimens and wash the mixture safely away after the photos were taken.

- 1. Head-on image of a cleared-and-stained Orangebanded Stingfish (Choridactylus multibarbus) with its lachrymal sabers projecting out.

- 2. Cleared-and-stained Timor Python (Python timoriensis) in a coiled position.

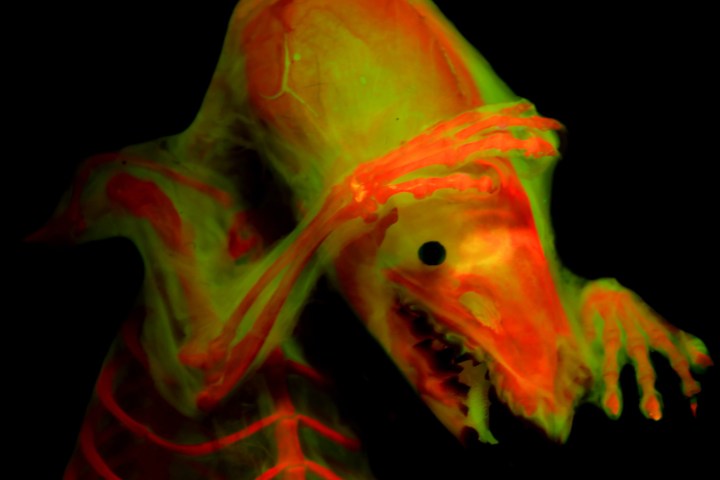

- 3. Cleared-and-stained head of a frightening deep-sea predator, Sloaned Viperfish (Chauliodus sloani).

The second technique involves fluorescent imaging, in which the researchers stain the specimen with the compound alizarin, which, years ago, W. Leo Smith, a professor of biology at KU, discovered fluoresces red when exposed to a specific light wavelength.

“The most exciting part of this effort is that you can use these techniques to create beautiful images,” Smith, who lead the study, told Digital Trends. “But perhaps more importantly, these techniques allow vertebrate biologists and paleontologists to more clearly demonstrate anatomical variation or discoveries that they make in publications and presentations. These techniques isolate the skeleton from other parts of the cleared-and-stained specimens and allow for the temporary posing of the … specimens in ways like museums pose dinosaurs or other large fossils on exhibit.”

Scientists have been snapping photos of specimens for science and posterity’s sake for hundreds of years. These allow them to share and disseminate these anatomical models, while keeping the original specimen in a safe location.

Today’s scientists — including biologists, paleontologists, and taxidermists — have already begun to use the technique developed by Smith and his team. He first began presenting the method a few years ago and recently detailed the technique in a paper in the journal Copeia.