The Japanese Space Agency, JAXA, has been exploring a distant asteroid named Ryugu with its probe, Hayabusa 2. After arriving at its destination 200 million miles from Earth, the probe managed to land on the asteroid in an incredible feat of engineering. Now the first results from study of the asteroid are in, with three new papers published.

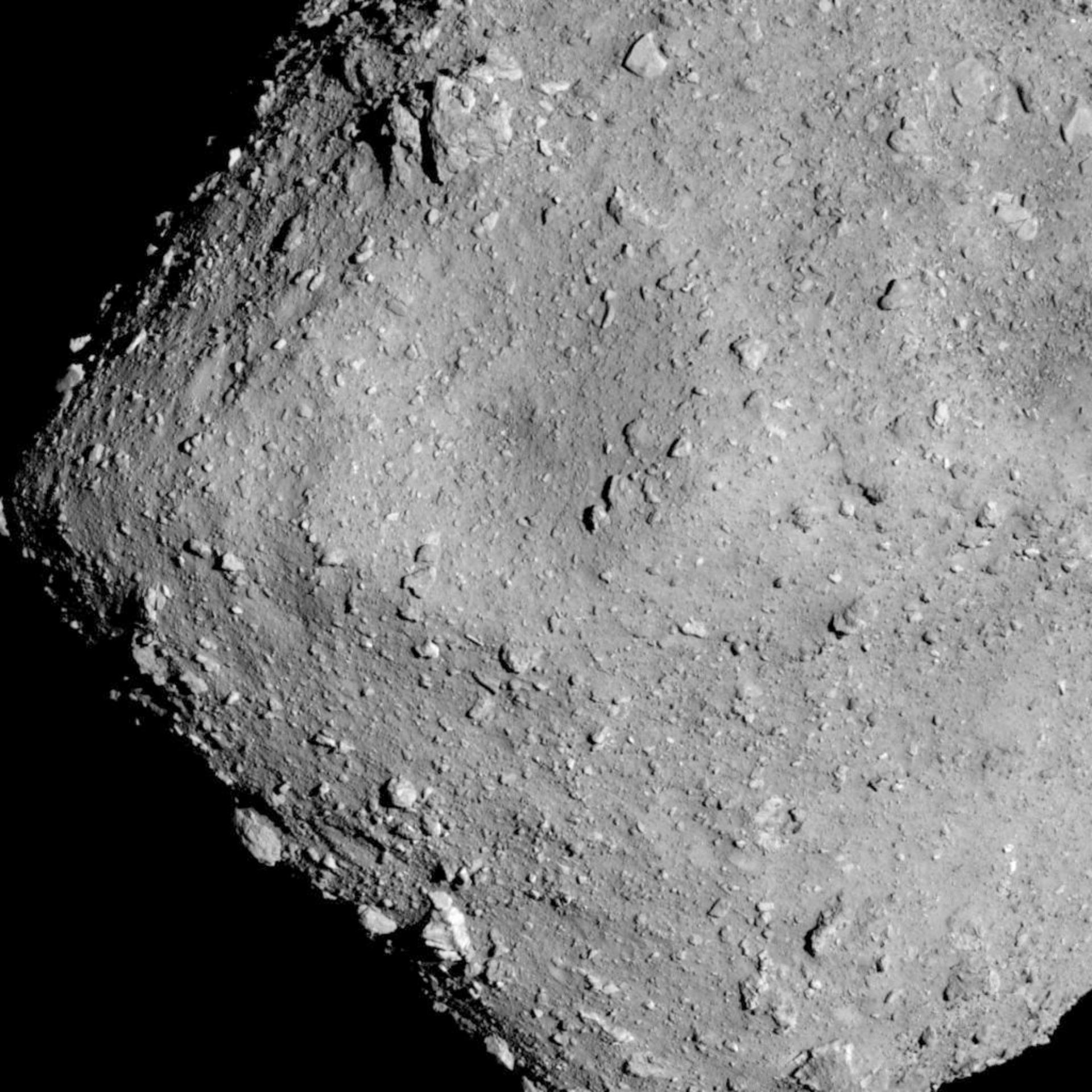

The first finding is that Ryugu is porous and only loosely held together. It has “large surface boulders [that] suggest a rubble-pile structure,” according to a paper by Dr. Sei-Ichiro Watanabe of Nagoya University, Japan, and colleagues. This means the asteroid is an aggregate of many smaller rocks which are bound together by gravity, with a low level of cohesion and a high degree of porosity.

In addition, the large boulders observed on the surface like the one named Otohime suggest that rock fragments were pulled together to form Ryugu as they are too big to have been created by impacts. Overall, the asteroid has a “spinning top shape” which is similar to another asteroid currently being studied, Bennu.

The second study looked at the surface composition of Ryugu. Using near-infrared spectrometery, scientists found that hydrated minerals were spread across the surface. However, the asteroid was much drier than was expected.

“Just a few months after we received the first data we have already made some tantalizing discoveries,” Dr. Seiji Sugita, a researcher at the University of Tokyo and the Chiba Institute of Technology and co-author of the three studies, said to Science News. “The primary one being the amount of water, or lack of it, Ryugu seems to possess. It’s far dryer than we expected, and given Ryugu is quite young — by asteroid standards — at around 100 million years old, this suggests its parent body was largely devoid of water too.”

In the final study, the authors combined data from the other two papers to try to understand the origin of Ryugu. “Small asteroids, such as Ryugu, are estimated to have been born from much older parent bodies through catastrophic disruption and re-accumulation of fragments during the Solar System evolution,” the scientists told Science News. “Ryugu likely formed as rubble, ejected by an impact from a larger parent asteroid.”

This information sheds light not only on the composition and formation of Ryugu, but could also be applied to the study of other asteroids like Bennu. “That Bennu and Ryugu may be siblings yet exhibit some strikingly different traits implies there must be many exciting and mysterious astronomical processes we have yet to explore,” Dr. Sugita said.

The three papers are published in the journal Science.