Bio-based materials, such as wood and spider silk, can be impressively strong. But not quite as strong as a new cellulose material developed by researchers from Sweden’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology. The new material is stronger than all previous bio-based materials, whether fabricated or natural. That includes previous record holder dragline spider silk fibers, generally considered to be the strongest bio-based material nature has yet created.

“One of the major challenges for anyone working with nanotech materials is how to make use of the properties that we know exist on the nanoscale,” researcher Daniel Söderberg told Digital Trends. “Nature has, through millions of years of evolution, been able to develop routes for this. An example is the wood that is built from the so-called nanocellulose, which trees build from water and carbon dioxide through biosynthesis. During growth, the tree manages to put the nanocellulose together in a controlled, ordered fashion. Nature is pretty good at this, and wood retains some of the properties of the nanocellulose. What we have done is to develop a process where we can make even better use of the strength and stiffness of nanocellulose, compared to the tree, and make a material out of it that could be used to build strong bio-based products.”

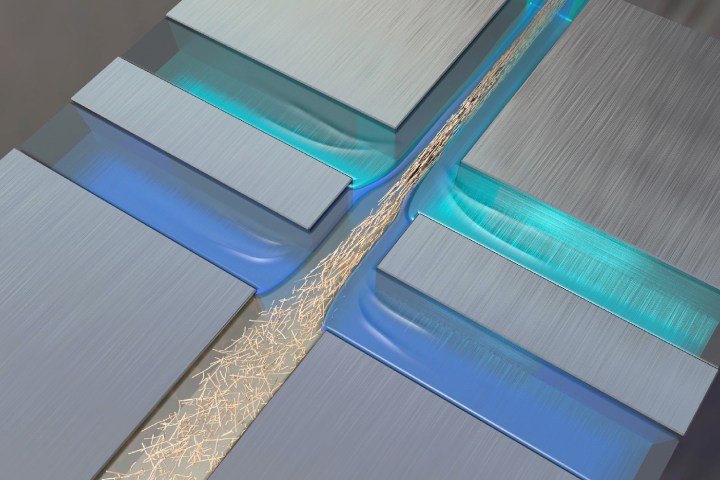

The team’s manufacturing process involves suspending nanofibers in very narrow channels, through which deionized and low pH water flows. This helps the cellulose nanofibrils to self-organize into tightlynbundled packages. The finished material is strong and stiff, but also lightweight. Along with spider webs, the nanocellulose fibers are stronger than metals, alloys, and ceramics.

Due to its apparent compatibility with the human body, the new bio-based material could be used for a range of medical applications. It could also be used for building everything from cars and planes to furniture. And because it is a bio-based material, it has the advantage of potentially being biodegradable.

Söderberg said that the team is currently working on scaling up the fabrication process. This involves overcoming several challenges, such as the speed with which the fibers can be made, and the ability to dry them. “Key questions that we are working on is simplification and parallelization — making several fibers at the same time,” he said.

A paper describing the work, “Multiscale Control of Nanocellulose Assembly: Transferring Remarkable Nanoscale Fibril Mechanics to Macroscopic Fibers,” was recently published in the journal ACS Nano.