The days are getting shorter, you just wrapped up your summer job washing cars, and in a week or two, you’re going to show up on campus with a hatchback crammed to the top with cardboard boxes and hangars. Fall semester is beginning, and besides the funds you’ve set aside for food and beer, you’re going to need a nice chunk set aside for the bane of all college students: textbooks. Pounds and pounds of textbooks.

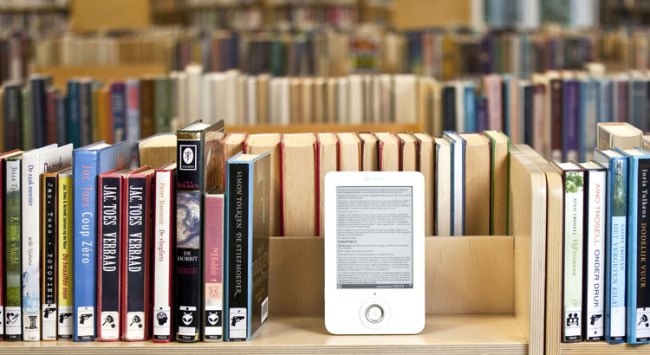

More recently, e-readers have promised to liberate college students from the heaving bundles of pages that most of them lug home from the bookstore at the beginning of every semester. From Amazon’s Kindle DX to Barnes & Noble’s Nook and even the iPad, a generation of digital readers promises to replace overstuffed backpacks full of musty textbooks with a lightweight, portable slate loaded with every book you’ll ever need for the entire semester – or every semester, for that matter.

But can you really just download the books you need for class? Are they cheaper? Do digital textbooks make any sense to begin with? We ran the numbers, considered all the factors, and the answers don’t all point to “buy.” Here’s everything you should consider before springing for an e-book reader this semester.

Portability

Portability

Nobody wants to hoof it to class looking like a hunchback, with 30 pounds of textbooks sagging off your back in a bag that looks like it’s about snap at the seams – if your spine doesn’t give out first. And therein lays the primary appeal of the e-book reader: Rather than 30 pounds, you’ll likely have just over one pound, in a package that’s typically as slim as a magazine. Readers like the Kindle DX weigh just 1.1 pounds, while the big daddy of the bunch, the iPad, hits only 1.5 pounds. A package that weighs and feels smaller than an average textbook can literally take the place of thousands of them. Thank, you technology.

Cost

Sure, Amazon’s Kindle DX will cost your $379 out of the gate, and Apple’s iPad will cost at least $500, but you’ll earn it back over time, right? Good question.

We made up an example schedule based on books a Syracuse University freshman might need for different introductory courses, to see how much you would actually save versus buying paper copies. The verdict: Money might not be a great reason to look into an e-reader.

We signed up for Spanish, writing, philosophy, religion and political science courses. The total tab for all the books we could buy online from the SU bookstore with one click came to $368.45. This included a total of 15 titles, buying used books whenever possible.

Then we went shopping on Amazon’s Kindle store. We had intended to compare the total cost of buying print versus digital, but the digital catalog was so incomplete we ended up comparing individual titles.

When comparing brand new, hefty textbooks, an e-reader can save a bundle. For instance, Writing Analytically would cost us $66.50 brand new from the SU book store, but we could download an e-book version instantly for just $46.30 on the Kindle. Total savings from just one book: $20.20.

Factor in the used-book market, and savings dwindle a little more. Let’s use Immigrant America: A Portrait as an example. It sells for $24.95 brand new from the Amazon store and the campus store. But the SU book store offered it to us used – automatically – for $18.75. Had we bought it for a Kindle, we could have scored it for $14.82 – savings of only $3.93 over the used paper copy.

Even those small savings dissipate when you consider that most students will sell their books after a semester. With Immigrant America, we could have turned around and sold our used paperback for $8.64 through online buyer AbeBooks, reducing our total cost to just $10.11 for a semester of use. We would actually pay more with the Kindle, since we can’t turn around and sell our digital copy. Even online rental services can’t match that: Chegg wanted $21.99 for a semester rental, CampusBookRentals wanted $18.92, and BookRenter wanted $18.95.

The bright spot for e-readers turns out to be old titles, which you can actually get for extremely cheap or even free. For instance, we could download The Book of Tea for free from Amazon, or pay $3.75 for the paperback. Ghandi’s autobiography was only 95 cents through the Kindle store, or $12 for the paperback.

Had we bought every single book possible through the Kindle store, we would have saved a grand total of $35.03 for the semester. That’s giving e-books the benefit of the doubt by comparing to only new paperback prices and not factoring in resale value. Other classes might offer more books online, but even if we were able to save double that every semester – $70 – we wouldn’t recoup the cost of the Kindle DX until six semesters in.

Availability

Availability

If the above example didn’t spell it out for you, or if you just want the Clif notes: You can’t just hop on Amazon or Barnes & Noble and buy all your books online. In fact, you can barely buy any of them.

Of the 20 books required for our courses, the SU bookstore offered 15 of them online in paper version. Amazon’s Kindle store offered four. So did Barnes & Noble.

The selection is bound to improve with time, but keep in mind that some materials won’t translate as readily. For instance, our Spanish materials included a CD loaded with video and workbooks, and some professors print specialized readers that only ever see distribution on college campuses. While we would like to think the videos could all eventually stream, the workbook sheets could be printed, and that professors might adopt the e-book format themselves, the slow-grinding, bureaucratic gears of academia and general fussiness of crotchety old professors suggests paper will reign in college for years to come.

Convenience

Besides the portability of the e-reader, students can look forward to spending less time deciding which books to bring to class, or making runs back to the dorm to swap the books needed for morning classes to books needed for afternoon classes. If you have your e-reader with you, you have a bookshelf in your backpack.

The frantic, last-minute run to the college bookstore also becomes obsolete. If an online store offers the text you need, you can tap on the screen and download it just seconds after a professor hands out the required reading list. Or right before he scolds you for showing up without it. Done, you overachiever, you.

Marking up

Marking up

If you’re the type of person who sees a crisp new textbook more as a blank canvas than a complete piece of work, you might want to think twice about going with an e-reader.

Although almost all e-readers include the option to annotate and highlight text, none of the examples we’ve tried come anywhere close to the ease of simply putting pen to paper, or swiping a highlighter across a few lines. In fact, some of them make it downright tedious. Unless you consider yourself extraordinarily patient and willing to invest extra time to record your thoughts and comments in the margins, a traditional book might make a better notepad.

Color

Plato’s Republic doesn’t really benefit much from illustrations. But that color pie chart in your economics book? The photo of indigenous tribes from New Guinea in your anthropology book? The Rembrandt painting in your art history book?

Yea, they’re all going to be in black and white on a dedicated e-reader, like a Kindle or Nook. Of the e-readers available on the U.S. market today, only the iPad really offers full color, which will make the rest of your reading quite monotonous. Pun intended.

Lending

We pointed out when evaluating the cost of e-books above that you can’t sell them, which strikes a major blow against a form of media that most people would just assume convert directly to beer money once they have a grade in a book. Well here’s a left hook to follow that uppercut: You can’t lend e-books. Your plan of splitting a book with two friends in your class and sharing it? Fat chance.

Sure, some e-readers claim they allow you to lend books, but not really. On the Nook, you can “lend” a book, but only if the publisher greenlights it, only for a period of 14 days, and only once, ever, for the lifetime of the book. Yes, we’re serious.

Other companies don’t even allow that much. Once you buy an e-book, you might as well tattoo it to yourself, because nobody else is going to use it – simultaneously or after you.

Multifunction

Multifunction

Comparing an e-reader with dead-tree books isn’t really fair unless you point out all the extra things an e-reader can do that books can never hope to touch. The Nook has games like chess. The Kindle can deliver blogs. The Alex can display Web pages. The iPad – if you group it with e-readers – is more like a full-blown computer that also displays books very nicely.

Depending on how much you’ll use any of these additional features – and which ones the reader you choose offers – they may tip scales in favor of the e-reader.

Conclusion

You will not be able to coast through college with an e-reader instead of a stack of pulp. Not yet, at least.

The scant textbook selection in e-book libraries will mean that your fancy new reader is more a supplement to your other textbooks than a replacement, and the tiny discount retailers offer for digital books will take years to justify the cost of the hardware. If you just want to get the books you need as cheaply as possible, buy as many of them used as possible, then sell them afterward.

That said, if you see yourself reading novels in your spare time outside class, playing chess before class starts and reading Digital Trends on your coffee breaks, an e-reader can easily make up its lack of educational prowess with fun factor to spare.