There’s a nondescript warehouse tucked behind an opera house in Copenhagen, Denmark, where a few dozen rocket scientists meet every week to discuss what has become their collective obsession: sending an astronaut into suborbital space.

That might not seem like such a feat. Russia ticked the suborbital box over 55 years ago, and NASA has literally sent people to the moon and back.

SpaceX could launch the world’s most powerful rocket by year’s end.

But considering that every member of Copenhagen Suborbitals (CopSub) is an amateur and a volunteer with a day job outside of the warehouse, the organization’s goal is one of the more ambitious in aerospace.

For nearly a decade, the exclusively crowdfunded group has built over a half-dozen unmanned rockets, launching them from floating barges out in the Baltic Sea. Some, like the Sapphire, pierced the sky in spectacular fashion. Others made more of an impression through their failures to ascend as expected, like the Nexø I, which reached less than 20 percent of its intended altitude before plummeting back into the Baltic.

The Sapphire pierced the sky in spectacular fashion.

I met with CopSub’s communications director, Mads Wilson, at the Copenhagen facility over the summer. “Do you see the big white rocket?” he asked. “That’s where we are.”

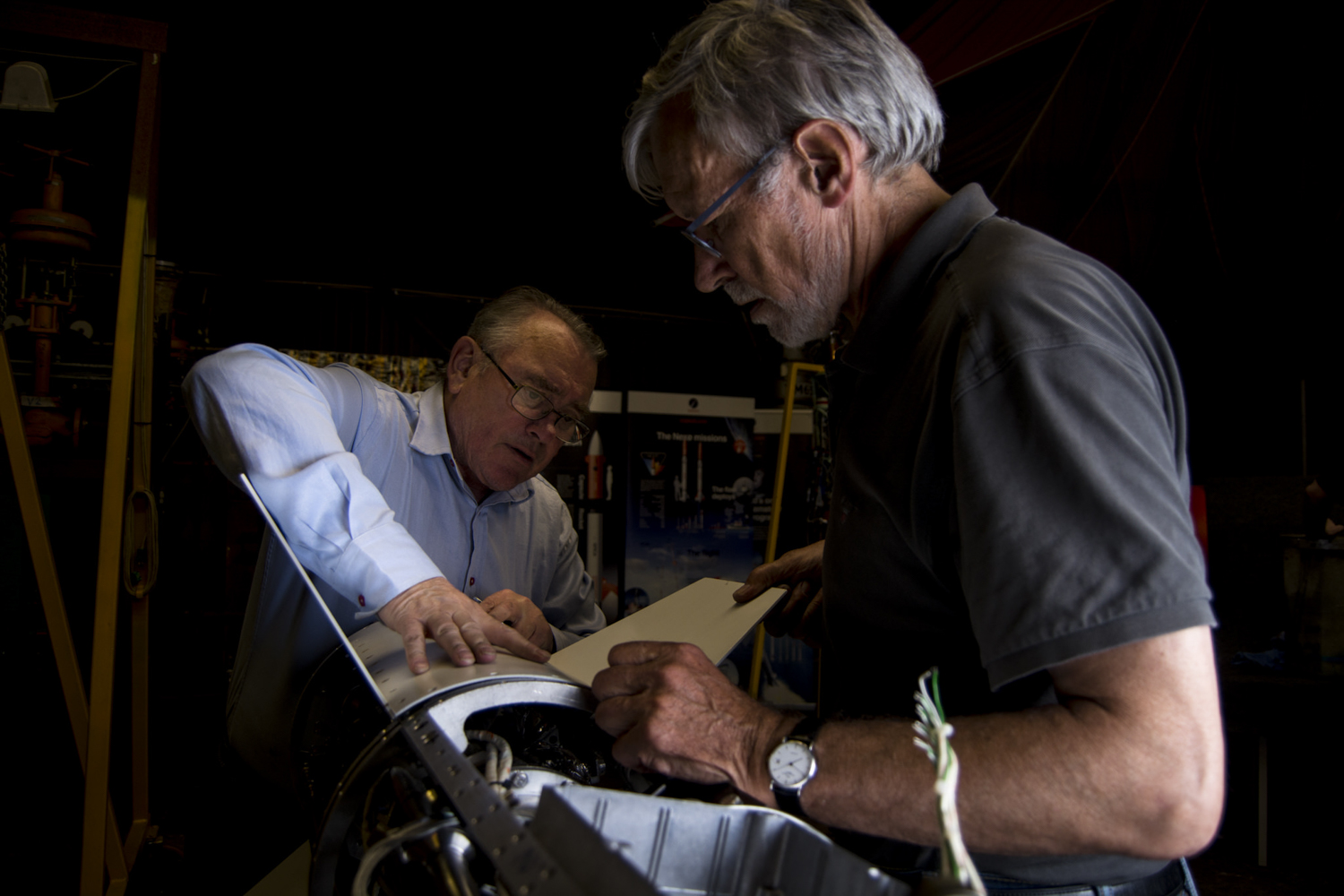

Although the group holds its weekly meetings on Sunday, there were still a few members about, toiling with electronics while the machine shop was silent. CopSub members are committed to its mission and, for many of its volunteers, the warehouse acts like a home away from home. But this isn’t NASA. The organization is relatively flat and roles often overlap.

The group is loosely divided into three teams. The rocket engine team works to refine the liquid propellant engines that boost the rocket vertically, whereas the computer and electronics team works on CSduino: a CopSub-developed variation of Arduino that serves as the rocket’s central nervous system. The communications team makes sure the rocket and its creators stay in contact during its mission.

In the future, these teams will have added roles and responsibilities once a human is strapped into the nose of the rocket. If all goes as planned, that amateur astronaut will be snugly positioned in the latest generation of CopSub’s Tycho space capsule (SpaceX recently revealed what that astronaut may wear).

But no one is sure just when that will be. Launching rockets is a tricky endeavor, and no shortage of variables — from rough weather to electrical malfunctions — have caused CopSub to reassess, delay, and even cancel a handful of launches. Even when they’ve managed to launch a rocket, many haven’t flown as planned, like last year’s Nexø I.

“The whole rocket is a system, and 99 percent went as it should,” Wilson said. “Even if just 0.5 percent doesn’t work, that can have a cascading effect.”

“Technology is not the problem. Time and money are the problems.”

In the case of the Nexø I, the rocket ended up on the launch pad longer than intended, causing the liquid oxygen in its tank to overheat and begin to boil. The rocket was thus left with too little fuel for its planned flight. Adding injury to insult, the parachutes failed to open because the computer system thought the rocket was still in flight. The rocket was devastated in its collision with the water, and CopSub has since updated its checklists to avoid such errors in the future.

But a checklist can’t save you from all unforeseen variables. This past summer, CopSub planned to launch the Nexø II, its final step towards the manned Spica class rockets. But after postponing the launch a few times, the team decided to reschedule for summer 2018 due to an array of internal and external stresses, from late deliveries to double-booked launch areas.

The Spica missions are CopSub’s ambitious aim to put an amateur astronaut just above the Karman line that delineates space — over 60 miles above Earth. Estimated to cost somewhere in the $1 to $2 million range, just for parts, Wilson said the team still needs three or four times its current budget for development.

“Technology is not the problem,” he said. “Time and money are the problems.”

Which is where the public comes in. CopSub is fueled by donations and takes to Indiegogo annually to raise funds, though its mainly funded by its 600 supporter members. The team hopes their efforts will engage people around the world and help democratize spaceflight (incidentally, that’s also the mission of tiny FemtoSats). But CopSub needs to triple its support group to fund its future projects, Wilson says. In jest, he calculates that NASA’s coffee budget could help send Spica to space in just a few years.

Whether CopSub can get a person into suborbital space in the foreseeable future is anyone’s guess. For now, space is beckoning these aerospace amateurs — but Earth’s gravity is holding them back.