The work is not only helping us understand more about the way that the first creatures to crawl out of the water moved, but also to learn valuable lessons that could make future robots more efficient at moving on surfaces such as sand and mud, which are typically tough to negotiate.

“I call the work that I do robo-physics,” Professor Dan Goldman, who worked on the project, told Digital Trends. “This isn’t a robot that’s designed to go out into natural complicated environments. It’s designed as a model of a biological life form we’re trying to understand — in this case an extinct organism. Using it we can discover incredible things we never knew about the movement of animals millions of years ago.”

So far the robot has helped researchers formulate theories, including the idea that early land-crawlers may have used their powerful tails more than previously thought — mainly as a means to propel themselves forward up steep slopes.

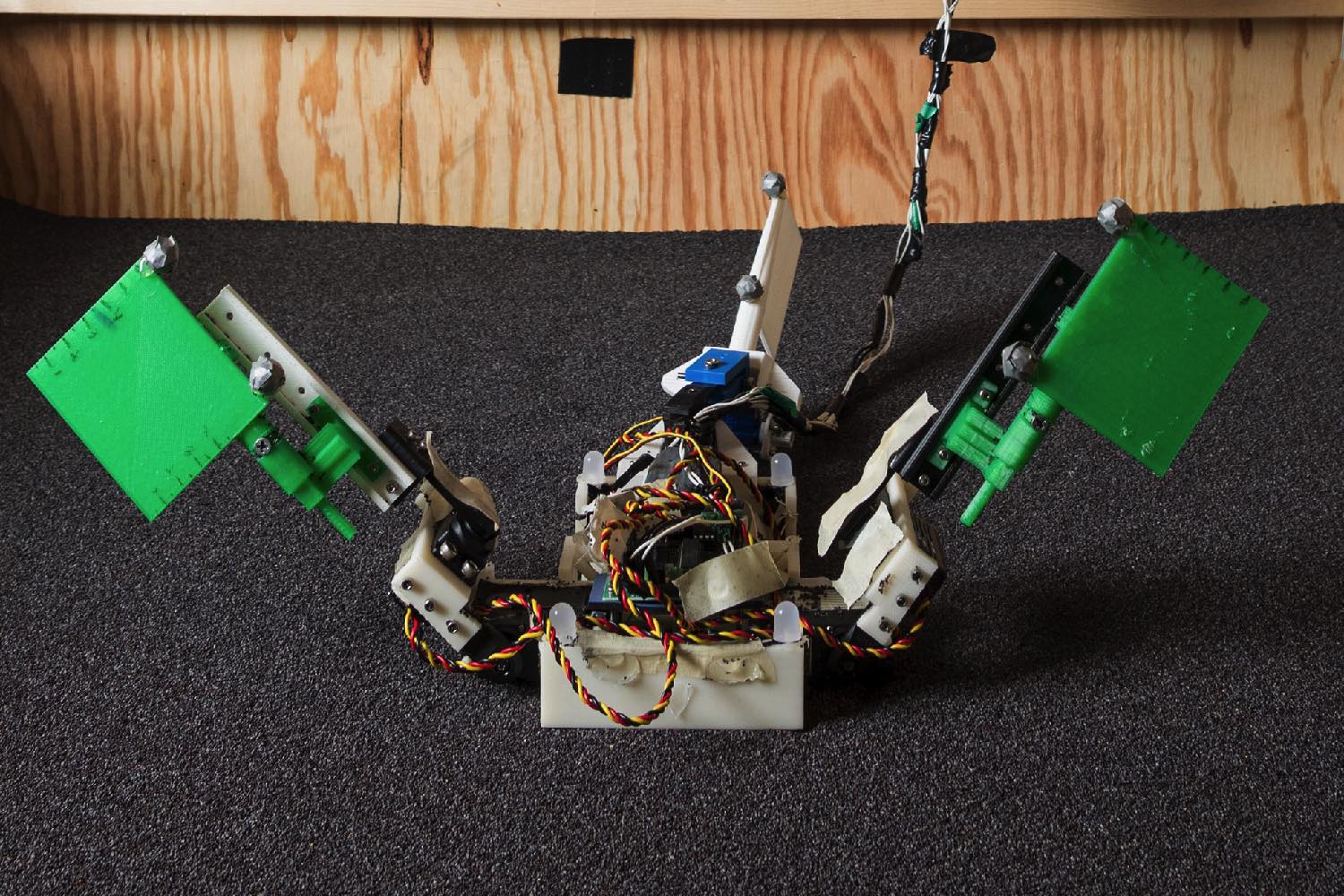

The so-called “MuddyBot” robot combined information from fossil records with 3D-printed elements and a mathematical physics-based model to help recreate the movement of prehistoric creatures.

“Building a robot is a great way of understanding the animal we’re studying,” Goldman continues. “You’re talking about an extinct creature interacting with environments like mud and sand banks, which present a challenge from a physics perspective. Mathematical modelling, along with building a physical robot, lets us isolate particular elements we think are important in the mechanical intelligence of the locomotor — and then figure out what it is about those elements that are important or unimportant for tasks.”

While MuddyBot remains a research project right now, the fact that the work is sponsored by the National Science Foundation, the Army Research Office, and the Army Research Laboratory suggests that the findings could one day be applied to real-world scenarios.

Doing so will help robots become even more versatile than they already are.