When you upload your DNA data to the internet, you can subject yourself and all your relatives to law enforcement DNA searches. That’s what eventually helped California police focus their hunt and arrest Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. as the suspected Golden State Killer.

Who was the Golden State Killer?

The Golden State Killer was a serial killer, serial rapist, and serial burglar who murdered at least 12 people, raped 45 others, and committed more than 100 residential burglaries from 1976 to 1986 in the California area.

Eight of the murders were conclusively linked by DNA evidence and two others were linked via modus operandi (MO). On April 24, 2018, Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. was arrested by the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department and charged with eight counts of first-degree murder.

From 1976 to 1986, the Golden State Killer murdered 12 people, raped 45 others, and committed more than 100 residential burglaries. For almost seven years, cold case expert and retired Contra Costa County District Attorney inspector Paul Holes searched genealogy websites for DNA matches to evidence collected at the crime scenes, according to The Mercury News.

A 73-year-old man in Clackamas County, Oregon had uploaded his DNA data to GEDMatch, an open-source genetic platform. When Holes compared the man’s DNA to samples taken from the crime scenes, he had a hit, but it was not an exact fit. Holes said it was a “weak match.”

Authorities subsequently obtained a court order to obtain a DNA sample directly from the Oregon man, who was cooperative. He was cleared of suspicion, but he and the Golden State Killer shared “an unusual trait.”

In the process of getting the court order, Holes said, “We generated the legal documentation more as a matter of routine, due diligence … But he was willing all along to provide his DNA.”

Subsequent searches resulted in narrowing the investigation to DeAngelo from a family tree with about 1,000 people. In the end, the matches that linked DeAngelo’s DNA to the crime were from third and fourth cousins.

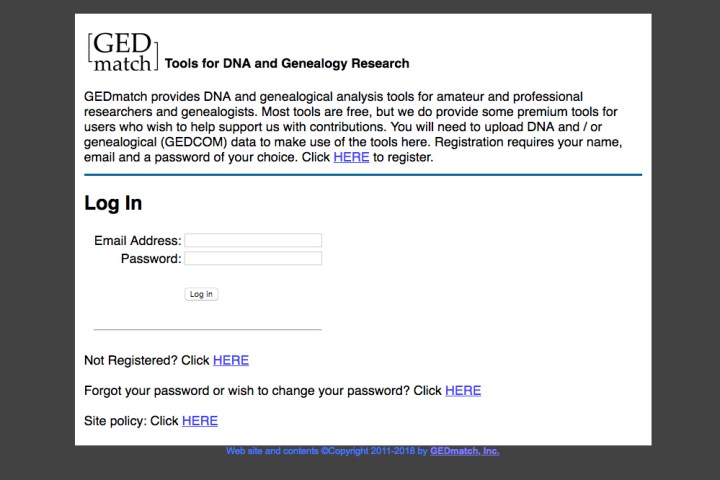

Commercial DNA ancestry-tracking companies require court orders for any files in their databases. Access to GEDMatch’s 900,000 DNA file open database has no restrictions, however.

GEDMatch co-creator Curtis Rogers didn’t know California officials searched the website for a DNA match. “I had no knowledge this was happening,” Rogers said, according to MIT Technology Review.

GEDMatch openly warns users that there’s no privacy guarantee. The site also informs users their DNA data could be accessed for uses other than ancestry searches. Still, the website rule is that DNA information is stored on the site “only with the person’s permission,” according to Rogers.

In the end, the matches that linked DeAngelo’s DNA to the crime were from third and fourth cousins.

UC Berkeley Boalt School of Law assistant professor Andrea Roth told The Mercury News, “When you put your information into a database voluntarily, and law enforcement has access to it, you may be unwittingly exposing your relatives — some you know, some you don’t know — to scrutiny by law enforcement. Even though they may have done nothing wrong.”

Concerns regarding the balance of privacy and public safety may be easily answered in the case of the Golden State Killer. Unfettered law enforcement access to our own and our relative’s DNA information has the potential for abuse, however.

“And even though it is easy to think of this technology as something that is used just to track down serial killers,” Roth said, “If we allow the government to use it with no accountability or no further safeguards, then all of our genetic information might be at risk for being used for things we don’t want it to be used for.”