Rythm founder Hugo Mercier gave Digital Trends an inside look at the design of the first consumer-ready Dreem product. A rigid piece across the top of the head contains all the headset’s electronics, and is lined with memory foam to ensure a comfortable fit. The headset may look intimidating at first glance, but Mercier promises it’s a feeling wearers will quickly get used to.

“The first time you wear Dreem, you feel something on your head for about five minutes, and then you forget about it after ten minutes.” she tells us. “And it gets better and better the more you use it.”

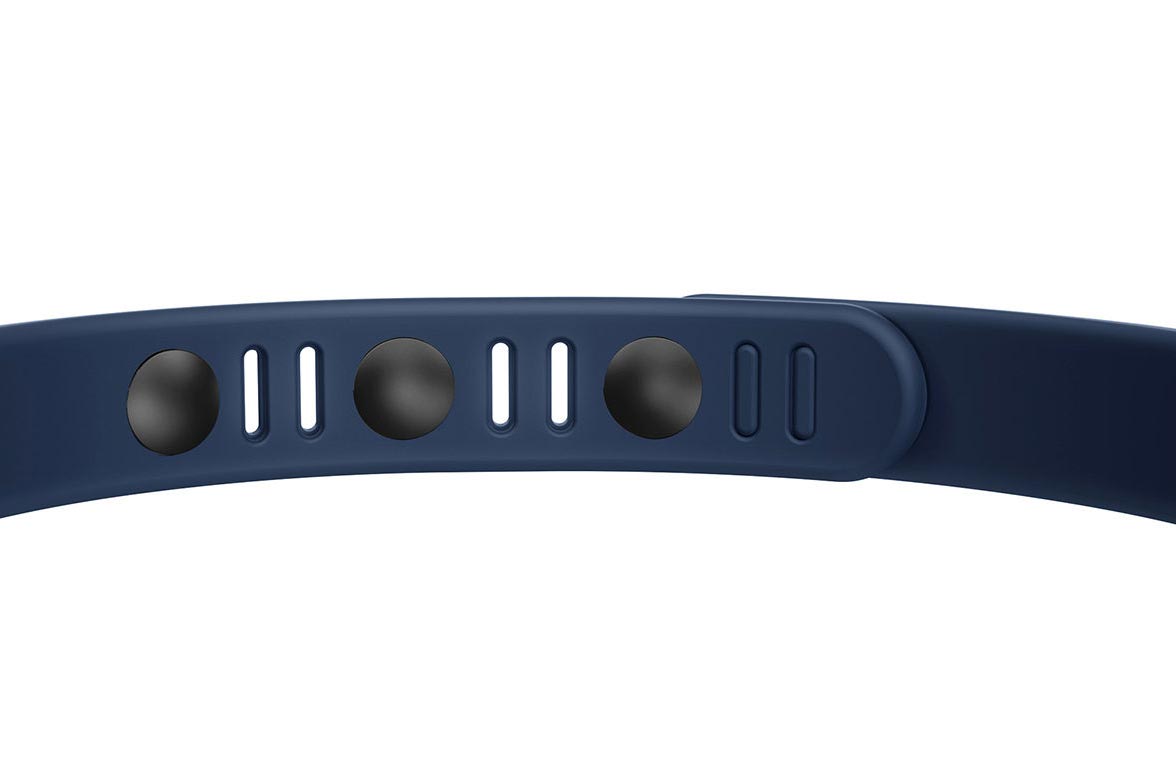

An adjustable band across the forehead features Dreem’s sensor technology. These EEG sensors and accelerometer tech work in combination with the thin, flexible pieces that tuck behind each ear to collect signal readings throughout the night. The raw data feeds into Rythm’s extensive sleep information database, and the processed results/analysis are fed back to the user through the accompanying Dreem mobile app.

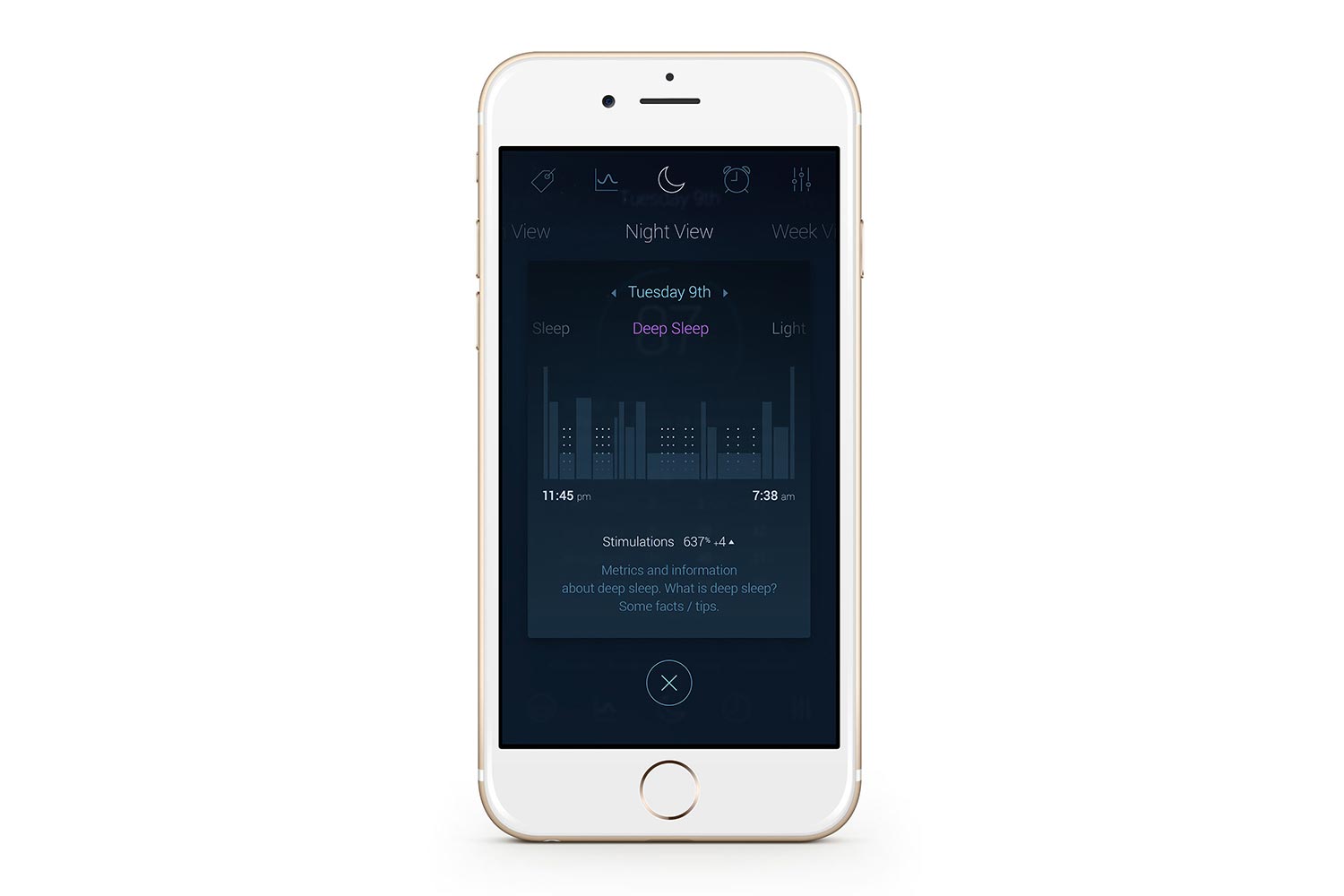

In order to avoid encouraging extra screen time before bed, Rythm focused on creating a mobile app that could be activated with the touch of just a few buttons. “We wanted to make it very simple to limit the time the user is spending on a phone before going to bed”, Mercier told us. Users can set a new alarm or choose from saved selections, and turn the phone off for the night. The Dreem headset works wirelessly, and data transfers over Wi-Fi and through a USB connection only when you wake up and plug in the device.

“We don’t want to improve sleep quality for the sake of improving sleep quality, but to improve cognitive and physical performance.”

When you wake up, the mobile app can show general or detailed views of your sleep last night, or over the past week or month. In addition to sleep monitoring, the app displays when auditory stimulation was emitted through the headset in order to prolong the deep sleep phase. At launch, the app will include a list of 30 activity options so that users can track their daytime habits that might influence sleep quality, like alcohol consumption, exercise, or even mood notes.

For Dreem users, auditory stimulation won’t come in the form of catchy alarm clock sounds. Rythm didn’t want Dreem users to have to sleep an entire night wearing uncomfortable earbuds, so its engineers turned to bone conduction technology. “A little burst of sound comes from the bone conduction device, is received in the inner ear, and the ear translates the vibration of the sound into an electrical impulse in the brain. That’s how hearing works, so if you have a speaker or bone conduction, it’s the same principal.” The Dreem headset’s bone conduction device is tucked away behind the forehead sensors. In addition to the alarm function, bone conduction sound is activated when the EEG sensors detect the user is in the deep sleep phase, working like a metronome to prolong the most restorative phase of sleep.

Mercier says that in Rythm’s growing database of sleep information, they have already seen an increase in quality of sleep and directly related cognitive and physical performance. “A lot of research correlates deep sleep with critical biological processes. During deep sleep you have memory consolidation, cellular regeneration, hormone release and regulation, it’s also what we call restorative sleep.” During Rythm’s beta testing program, Dreem First, 500 users will get access to the current Dreem product for hands-on testing and development.

In parallel with the Dreem First, Rythm will be running clinical trials with Dreem users in the French army. Mercier says that soldiers offer an interesting contextual element because of their chronic sleep deprivation while in training and on deployment. “We don’t want to improve sleep quality for the sake of improving sleep quality, but to improve cognitive and physical performance”, Mercier told us. If Dreem can improve sleep quality and daily performance of strained soldiers, that will be a very powerful study.

Since Rythm is a neurotechnology company with a strong research foundation in engineering, mathematics, and computer science, they’re proud of the proprietary technology the company has created to fit Dreem. But Mercier knows that what will really matter to Dreem users is the direct benefit of using the world’s first active sleep wearable. “The main competitive advantage about Dreem is that we are active. We are not only measuring brain activity, we are doing simulations that directly improve sleep quality.”

Once the Dreem First beta testing program is completed, Rythm expects to launch a mass-market version of the Dreem headset to consumers by the beginning of 2017.