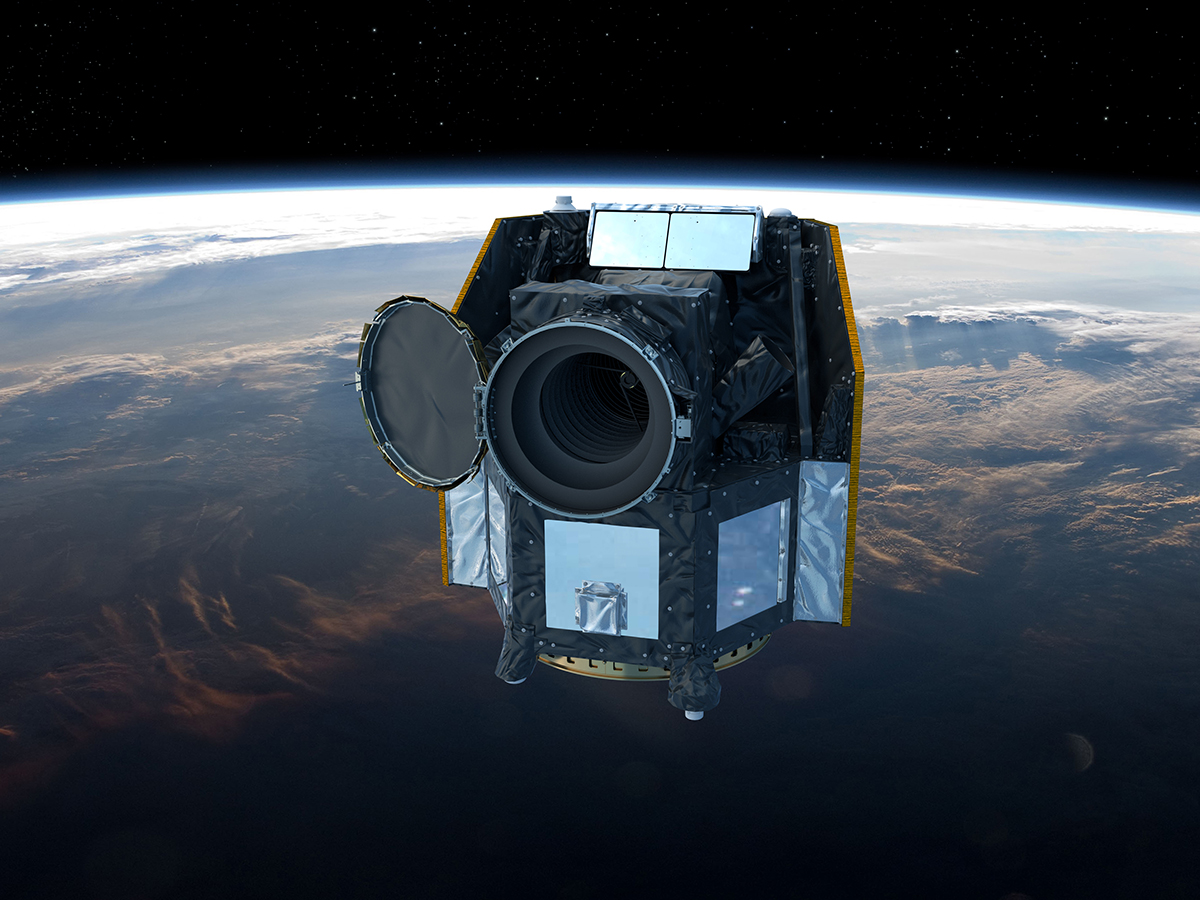

The European Space Agency (ESA)’s new exoplanet-hunting instrument, the CHaracterizing ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS), has opened its eyes to observe the universe for the first time.

The ESA launched the CHEOPS satellite in December last year. Since then, it has been orbiting the Earth at an altitude of 700 kilometers (435 miles) while scientists performed various tests to make sure all the components were working as they should.

“Shortly after the launch on December 18, 2019, we tested the communication with the satellite,” Willy Benz, professor of astrophysics at the University of Bern and Principal Investigator of the CHEOPS mission, explained in a statement. “Then, on January 8, 2020, we started the commissioning, that is, we booted the computer, carried out tests, and started up all the components.”

The tests went well, with no issues reported. But there was still one big challenge for Benz and his colleagues: Opening the cover of the space telescope, which protects the instrument during launch. “We were now looking forward excitedly and with a bit of nervousness to the next decisive step: the opening of the CHEOPS cover,” Benz said.

On Wednesday, January 29, the cover was opened for the first time. “The cover was opened by sending electricity to heat an element which held the cover closed,” Benz explained. “The heat deformed this element and the cover sprung open. A retaining fixture caught the cover. Thanks to the measurements of the sensors installed, we knew within minutes that everything had worked as planned.”

Now CHEOPS can begin its mission of observing exoplanets, in particular, to search for habitable planets. “In the next two months, many stars with and without planets will be targeted in order to examine the measurement accuracy of CHEOPS under different conditions,” Benz said.

We shouldn’t have to wait long to see the first CHEOPS images of space. CHEOPS has taken hundreds of images already, even though these were all black because the cover was closed, so the scientists have already been able to calibrate the instrument.

Even though it will take a while for the researchers to confirm that the CHEOPS satellite is operating correctly in every way, there should be images available to view soon, according to David Ehrenreich, CHEOPS project scientist at the University of Geneva: “We expect to be able to analyze and publish the first images within one or two weeks,” he said.

Editors' Recommendations

- Hellishly hot planet orbits so close to its star that a year lasts a few days

- Watch the European Space Agency test its Mars rover parachute

- Ingenuity helicopter explores Mars on its own for the first time

- Here’s what the James Webb Space Telescope will study in its first year

- All the weird and wonderful exoplanets CHEOPS investigated in its first year