It’s understandable how these particular machines can be funny to observers since we don’t actually rely on them to work. But a new study suggests that people really do prefer faulty robots, even when they are intended to be functional.

“From our previous research on social robots, we know that humans show observable reactions when a robot makes an error,” Nicole Mirnig, corresponding author and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Salzburg, told Digital Trends.

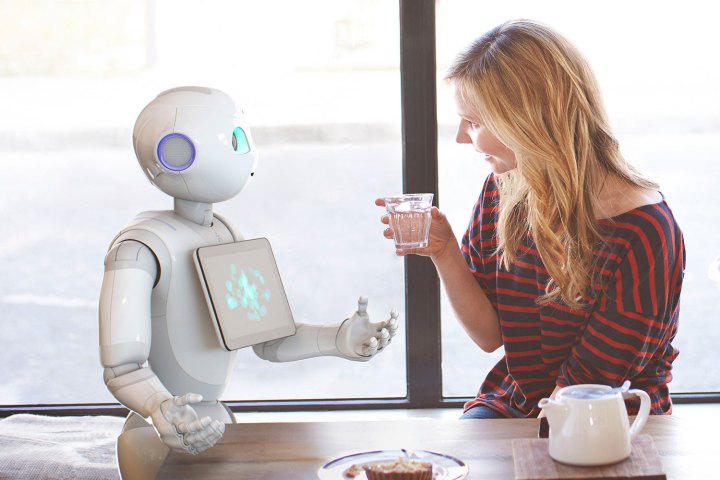

To err is human and mistakes make robots feel more human-like.

Mirnig and her team at the Center for Human-Computer Interaction wanted to explore this idea further, to study how and why people react to faulty robots. They intentionally programmed certain robots to screw up while making their counterparts perform actions perfectly.

After analyzing participant reactions and interviewing them about their experience with the robots, the researchers discovered the participants did not consider the faulty robots any less intelligent or relatable than those robots that performed the tasks perfectly. In fact, the participants rated faulty robots as more likable than their flawless counterparts.

It’s not obvious why people would be inclined to like faulty robots. One explanation may be the “Pratfall effect,” which occurs in people when someone’s attractiveness increases after he or she makes a minor mistake. The reasoning here: To err is human and mistakes make robots feel more human-like.

“Research has shown that people form their opinions and expectations about robots to a substantial proportion on what they learn from the media,” Mirnig said. “Those media entail movies in which robots are often portrayed as perfectly functioning entities, good or evil. Upon interacting with a social robot themselves, people adjust their opinions and expectations based on their interaction experience. I assume that interacting with a robot that makes mistakes, makes us feel closer and less inferior to technology.”

For Mirnig and other at the Center for Human-Computer Interaction, the goal is not necessarily to develop robots infallible robots but to develop robots that understand when they made an error.

“If a robot can understand that an error is present, it can actively deploy error recover strategies,” Mirnig said. “We believe that this will result in more likable robots that are better accepted.”

A paper detailing the study was published in the journal Frontiers in Robotics and AI.