Agriculture has come a long way in the past century. We produce more food than ever before — but our current model is unsustainable, and as the world’s population rapidly approaches the 8 billion mark, modern food production methods will need a radical transformation if they’re going to keep up. But luckily, there’s a range of new technologies that might make it possible. In this series, we’ll explore some of the innovative new solutions that farmers, scientists, and entrepreneurs are working on to make sure that nobody goes hungry in our increasingly crowded world.

Ever since American citizens’ industrial age migration from the country to the city, urban areas have tended to be associated with cutting-edge technologies.

Well, scratch that correlation — because in the age of artificial intelligence, a new research project by Carnegie Mellon University’s Robotics Institute is setting out to prove that the country can be every bit as technologically advanced as the smart city.

Called FarmView (not to be confused with FarmVille, the time-wasting game that has overrun Facebook feeds for much of the last decade), the project employs machine learning, drones, autonomous robots, and virtually every other area of big-budget tech research to help farmers grow more food, better and smarter.

“We’ve been doing research into robotics for agriculture for about 15 years now,” George Kantor, Carnegie Mellon senior system scientist, told Digital Trends. “It’s taken a number of different forms, and this was an attempt to pull it all together into one cohesive project.”

“The world population will hit 9.6 billion by 2050.”

But FarmView is way more than just a top-down organizational reshuffle, like making the finance administration team responsible for accounts receivable instead of accounts payable. In fact, it demonstrates a new sense of urgency around this topic, thanks to a statistic that hammered home its importance to the researchers involved.

That stat? According to current predictions, the world population will hit 9.6 billion by 2050. What that means is that if better ways aren’t found to use our limited agricultural resources – including land, water, and energy – a global food crisis may well occur.

“That’s a statistic which really forces us to look for solutions,” Kantor continued. “Technology alone isn’t going to solve this potential crisis; it also involves social and political issues. However, it’s something we think we can help with. It’s not just about how much food there is, either. The way we produce food right now is very resource intensive, and the resources that are available are being used up. We have to increase the amount of food we produce, as well as the quality, but do so in a way that doesn’t assume we have unlimited resources.”

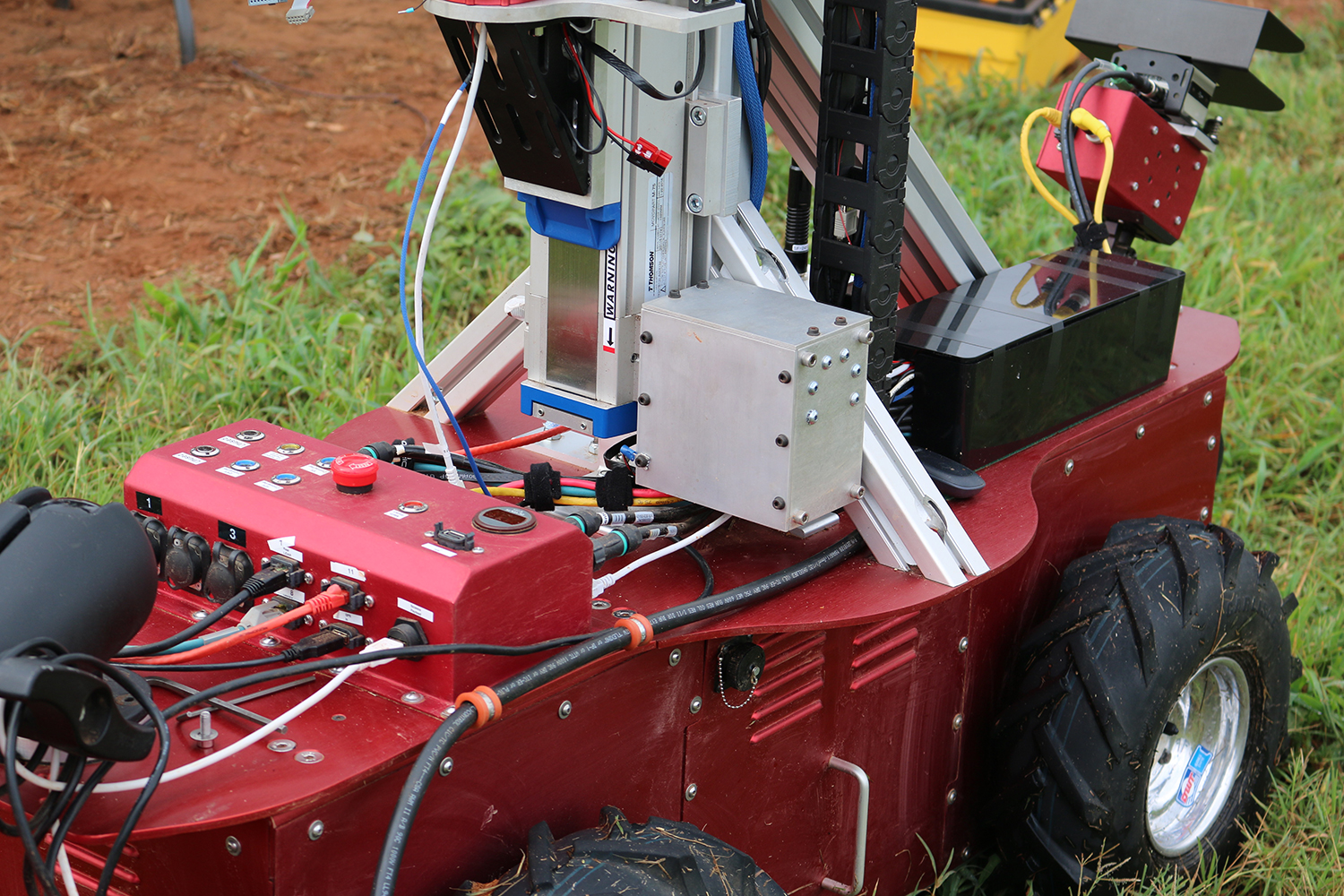

As part of the project, the team has developed an autonomous ground robot capable of taking visual surveys of crop fields at different times in the season — courtesy of a camera, a laser scanner to measure plant geometry, and a multispectral camera that looks at nonvisible radiation bands. Using computer vision and machine-learning technology it can predict the expected fruit yield later on in the season.

Rather than just passively passing on this information to a farmer, however, it can then actively trigger the robotic pruning of leaves or thinning of fruit in a way that maintains an optimal ecological balance between leaf area and fruit load.

CMU researchers also use a combination of drones and stationary sensor networks to take macroscale measurements of plant growth.

“Our push now is to start using these tools to solve problems on a large scale.”

While these are definitely smart examples of technology, the really long-lasting impact is going to come from how technologies like leaf-cutting robots and drones can be used to help improve crops.

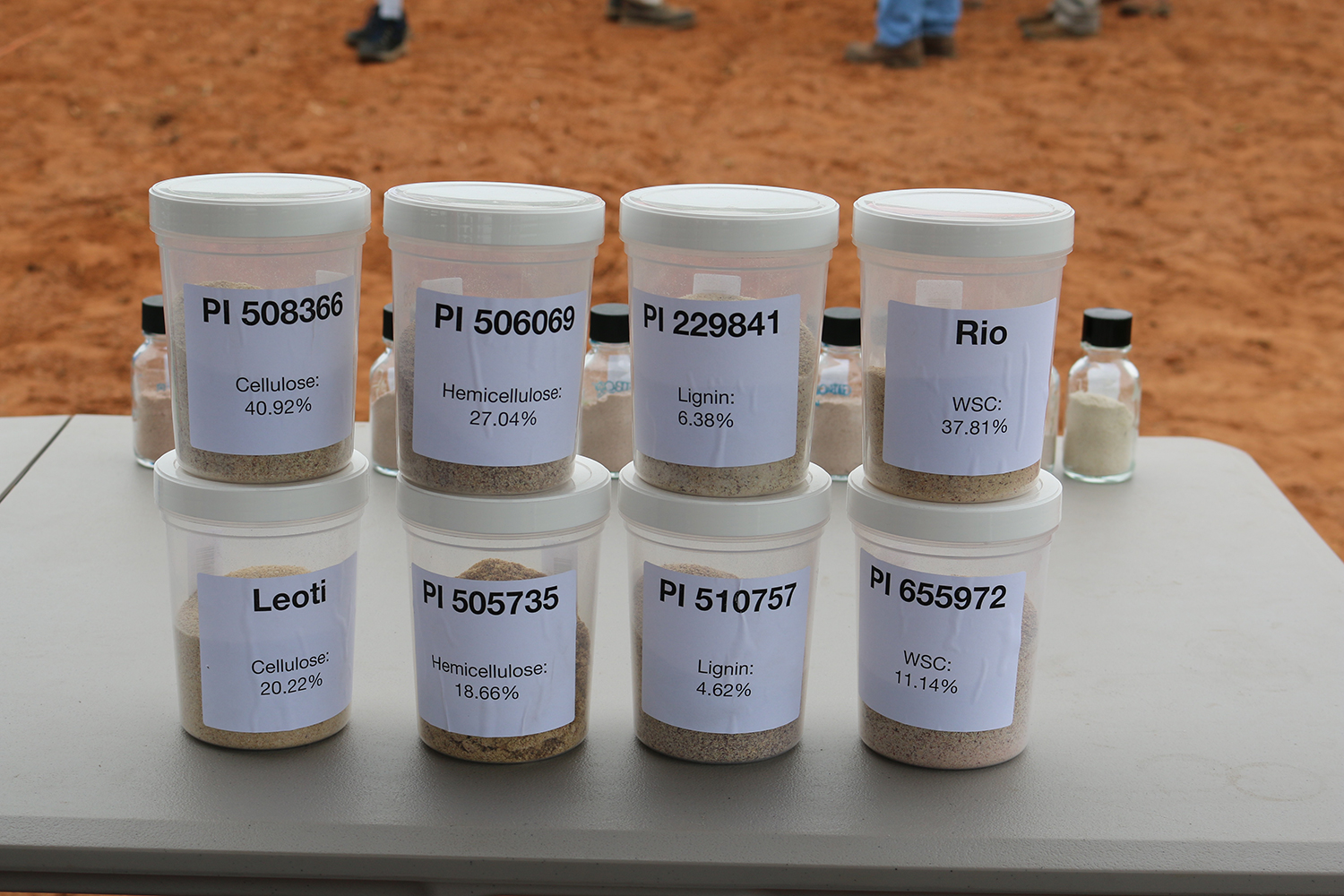

In this capacity, Kantor pointed toward the crop sorghum, a coarse, dry grass grain that originated thousands of years ago in Egypt. Grain sorghum is widely eaten, and is considered the fifth-most important cereal crop grown in the world. Because it features so many different varieties (a whopping 42,000!), it also has enormous genetic potential for creating new high-protein varieties that could make it even more important.

After all, who’s satisfied with simply being the fifth-most important cereal crop?

That’s where AI comes in. If it’s possible to use machine-learning technology to measure sorghum parameters in such a way that breeders and geneticists can choose the traits most necessary for improved yield, as well as most resistant to disease and drought, it could have a massive positive impact. Just improving the yield alone by, say, 50 percent would represent a realworld impact that very few computer scientists can ever be credited with.

So does this all of this mean that the farm of the future, like the factory of the future, will be largely free of humans — with row after row of gleaming Terminator-style robots carrying out all the work? Not quite.

“We’re not doing this to replace people. What we’re doing is to introduce new technologies that can make farmers more efficient at what they do, and allow them to use fewer resources to do it,” Kantor said. “The scenario we envision doesn’t involve using fewer people; it involves using robotics and other technologies to carry out tasks that humans aren’t currently doing.”

At present, many of the technologies are still at the “proof of concept” phase, but Kantor noted that they’ve had some interesting discussions with agricultural early adopters. Now the project — which also includes folks from Texas A&M, Penn State, Colorado State, Washington State, the University of Maryland, University of Georgia, and South Carolina’s Clemson University — is preparing to hit the big time.

“A lot of people don’t think of this as being the first place to do this kind of research and development, but it’s an area that — and I’m sorry to use this pun, but it’s really unavoidable — is really ripe for progress,” Kantor concluded. “Our push now is to start using these tools to solve problems on a large scale.”