Agriculture has come a long way in the past century. We produce more food than ever before — but our current model is unsustainable, and as the world’s population rapidly approaches the 8 billion mark, modern food production methods will need a radical transformation if they’re going to keep up. Luckily, a range of new technologies might help make it possible. In this series, we’ll explore some of the innovative new solutions that farmers, scientists, and entrepreneurs are working on to make sure that nobody goes hungry in our increasingly crowded world.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, or have had your head buried in an empty mining bee hive, you’ve probably heard about the current “beepocalypse.” Over the past few years, colony collapse disorder (CCD) has ravaged bee populations worldwide. More than 40 percent of colonies in the United States died in 2016 alone, so to call the plight a “decimation” would be a gross understatement.

Nearly one-third of our diet comes from insect-pollinated plants, and according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, bees are responsible for 80 percent of that pollination. Needless to say, an enormous portion of our global food network hinges on the well-being of this unsung agricultural workforce. Simply put: If they go, we go.

There are a slew of underlying causes behind this massive die-off, and consequently, there’s no silver bullet that will reverse the trend. The issue is a multifaceted one, and solving such a labyrinthine problem will require a web of complementary efforts.

Luckily, planet Earth already has somebody on the case.

Right now, all over the world, conservationists, engineers, and everyday citizens are leveraging modern technology to help save our buzzing, winged allies. In this article, we’ll take you on a tour of not only the biggest problems facing beekeepers right now, but also some of the amazing solutions people have dreamed up to solve them.

Turns out that pesticides are bad for bees. Who knew?!

Over the past few decades, farmers have looked to genetically modified crops and a new class of pesticides — namely neonicotinoids (or neonics) — to stretch yields to meet our global food demands. Unfortunately, the residual effects of these crops and pesticides have been directly linked to higher rates of colony collapse disorder — a phenomenon in which the majority of worker bees abandon the hive and leave their queen behind.

Even if we stopped using neonics worldwide yesterday, our problems wouldn’t be over.

Therein lies the conundrum. We rely on these agricultural chemicals to produce adequate amounts of food for ourselves, but they’re also killing bees and chipping away at a crucial pillar of our food system. Scientists say we probably shouldn’t keep using neonics, but farmers will likely continue to do so because they boost crop yields. It’s a vicious cycle.

The good news is that lately, more and more countries are beginning to ban some of these pesticides — thereby forcing growers to figure out alternative methods. However, even if we stopped using neonics worldwide yesterday, our problems wouldn’t be over.

Pesticides are just the tip of the iceberg

Big Ag and the bastardization of beekeeping

Commercial beekeeping has always been a lucrative business. However, in recent years, beekeepers have begun renting out more and more of their hives for pollination purposes (rather than simply making honey) to remain profitable.

This is often done on a massive scale, incorporating semi trucks loaded with hundreds of hives and millions of bees. These beekeepers travel the highways following the pollination cycles across the country and rent out their colonies to the highest bidders.

Bees, however, are quite finicky. If the temperature dips below 50 degree Fahrenheit, or if it’s rainy, particularly windy, or even cloudy, bees are less likely to leave the hive and pollinate. To guarantee a crop is pollinated, farmers will often utilize commercial beekeepers as an insurance policy of sorts.

Many will often rent double the necessary number of bees for a given crop in order to ensure it gets pollinated no matter what. Unfortunately, this generally means there is half the amount of food in a given field to adequately nourish the bees. To compensate for this imbalance, many beekeepers will supplement their bees’ diet with alternate food sources. This is usually includes cheap, less nutritious corn syrup to further buoy profitability.

“Just because of the way [beekeepers] have to manage them in high numbers of colonies to make money is detrimental to their health,” says Dr. Francis Drummond, a professor of insect ecology at the University of Maine. “So it’s sort of a catch-22.”

Corn syrup isn’t as nutritious as cane sugar, and cane sugar isn’t nearly as nutritious as nectar from flowers. Similarly, the current system of perpetual transportation is also stressful and detrimental to the overall health of these commercial bee populations, making them more susceptible to disease and parasites.

Like a FitBit for bees, the system uses cameras inside of the hive to monitor activity.

“Anytime you have a population of a host that is infected by a parasite or disease, and also kept at really high densities, they tend to be more prone to acquiring that disease,” said Drummond.

One way to combat this is with better monitoring tech that allows beekeepers to bolster healthy populations and mend sick ones. Take EyesOnHives, for example. Like a FitBit for bees, the system uses cameras inside of the hive to monitor activity and relay data to beekeepers via a smartphone or tablet.

With the help of software, hours of hive surveillance can be broken down into colony activity patterns to provide useful analytics. The application collects data not only on individual bees but also monitors the hive as a cumulative “superorganism.” This allows the app to gauge hive health via analytical spikes and dips so keepers can react to disruptions more quickly.

And boy, are there plenty of disruptions to be worried about.

Fight the mite

The Varroa mite — or Varroa destructor as it is formally known — has ravaged bee colonies worldwide for decades. Since the invasive species’ introduction to North America in the late 1980s, the pest has been responsible for wiping out entire populations of Western honeybees.

It’s easy to see why. Western honeybees are completely defenseless against the mite. The parasite — no bigger than a sesame seed, latches onto a bee and sucks its blood, eventually either killing it outright or making the bee more susceptible to disease and viruses. To make matters worse, beekeepers don’t really have much recourse when it comes to these mites, and are often forced to use everything from acids and bleach to horse tick medicines to combat them. But of course, these too can have negative effects on the colony.

Thankfully, there may be a safe solution to our destructor problem.

The creators of the hive claim it accelerates spring colony growth, pollen-collection capacity, and flight activity. The hive is still in the prototype phase at this point, but could be a powerful weapon in the fight against the mite.

Of course, if this simple approach doesn’t pan out, there’s a backup plan. In a future with cornucopias of genetically modified foods, we may also have hives humming with genetically modified honeybees.

Engineering better bees — and building robots just in case

Another plan to mitigate the Varroa mite problem comes from Mother Nature — with a twist. The idea is to use a technique called RNA interference (RNAi) by feeding bees sugar syrup with synthetic RNA code that’s specifically designed to work against the Varroa mite. When a mite begins to leach blood from these biotech bees, a synthetic RNA enters its system. Rather than being nourished, the pest is instead left with a diminished ability to breathe, eat, or reproduce — and that’s just one of the many clever approaches that researchers are dreaming up.

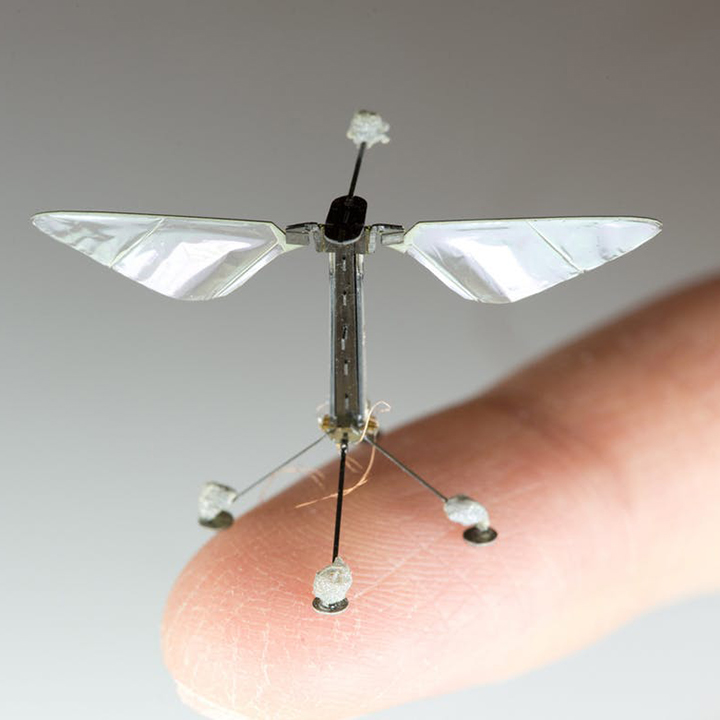

Harvard University is taking things a step further by planning for an all-out Silent Spring scenario: A world without naturally occurring bees. At the university’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Robots, researchers are designing entire fleets of so-called “RoboBees” that might pollinate our crops in a bee-less future.

These RoboBees (or more accurately, Autonomous Flying Microbots) are not only equipped with wings, but also sensors that mimic the eyes and antennae of bees, thereby allowing the units to both “sense” and respond to their environment. It may sound crazy and far-fetched, but this isn’t just academic vaporware. The team has been developing these robots for more than five years, and believes RoboBees could begin artificially pollinating crops within a decade.

It’s a promising project, and could very well end up saving the day — but it’s also important to remember that us regular Joes aren’t at the behest of the latest technology to reverse the beepocalypse. There are plenty of basic steps cities and citizens alike can take to actually make a difference.

Building bee-friendly cities

One of the most problematic results of both large-scale farming and climate change is the depletion of biodiversity in favor of monoculture. A diet of predominantly one food source is not ideal for optimal bee health. An area dominated by tens of thousands of acres of single, seasonal crops cannot adequately nourish a healthy hive year-round — let alone seasonally.

While cities are constructed for humans, the spaces can be easily adapted to act as bee sanctuaries. An impressive effort underway in Oslo, Norway, could be implemented in cities around the globe to revive colonies locally. They call it the world’s first “bee highway.”

As part of the project, citizens are encouraged to use outdoor spaces (parks, school gardens, roofs, etc.) to create bee-friendly habitats around Oslo. Individuals can list and map their planting efforts on a website to encourage others nearby to follow suit with their own habitats and other diversified gardens.

Oslo isn’t the only place where people are rethinking urban design with pollinators in mind. Researchers at the University of Maine are working with a full landfill in Hampden and repurposing portions of the site for a similar project. Maine is primarily dominated by forest ecosystems. Unfortunately, these areas are not exceedingly conducive to bee health. Professor Frank Drummond and others are planting pollinator gardens at the inactive Pine Tree Landfill to identify plants that are most beneficial to bees in the area.

Other U.S. states are also starting to better utilize roadside vegetation in an effort to promote plant diversity specifically geared toward bees. To aid in this endeavor, the U.S. Department of Transportation plans to conduct a study this spring to determine what roadside vegetation pollinators are consuming. The data will be used to promote biodiversity and stronger pollinator habitats along right of ways.

Moving forward

By attempting to create an efficient food supply network, we’ve unwittingly turned the entire apparatus into an unpredictable mess.

“Unfortunately, if you take a really close look at a lot of agriculture, it’s clear that we are very dependent on what you might call outside inputs,” said Drummond. “Whether it’s living organisms like honeybees or petroleum-based fertilizers and pesticides, that’s the way large-scale agriculture has gone. It’s just sort of where we are, but it does make our agriculture vulnerable to disruptions. I would say it’s sort of become a fact of life until something happens.”

Fortunately, some ingenious high- and low-tech options are already well underway.

Do we need to build a smarter, more efficient, less destructive global food supply? Absolutely. Will this happen overnight? Don’t hold your breath. In the meantime, we must take steps to prop up our chief pollinators on a micro level, or we couldbe next on the chopping block.

As truly beautiful as it is to imagine a fleet of RoboBees pollinating the countryside, it might be best to heed the warning of the canary in the coal mine, because our pollinators are dropping like — well, bees, at this point.